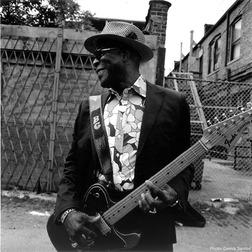

Buddy Guy is the epitome of Chicago electric blues. More so even than the men he idolized and worked with, Buddy Guy has influenced the cream of the crop of modern blues players--Eric Clapton, Stevie Ray Vaughn, Jimi Hendrix and Jimmie Page, to name just a few. His first book, When I Left Home (reviewed below), was written with David Ritz, a well-known biographer and co-author of such soul and R&B luminaries as Ray Charles, Smokey Robinson, Aretha Franklin, Marvin Gaye and Janet Jackson.

Buddy Guy is the epitome of Chicago electric blues. More so even than the men he idolized and worked with, Buddy Guy has influenced the cream of the crop of modern blues players--Eric Clapton, Stevie Ray Vaughn, Jimi Hendrix and Jimmie Page, to name just a few. His first book, When I Left Home (reviewed below), was written with David Ritz, a well-known biographer and co-author of such soul and R&B luminaries as Ray Charles, Smokey Robinson, Aretha Franklin, Marvin Gaye and Janet Jackson.

Why did you want to write a book?

You know, David came to me, and I knew about him, and we sat down and had a talk. And what got me more into it is the fact that most of those great guys are not here to answer those questions he had from me. I didn't learn nothing in school, trust me. Everything I learned, including playing my guitar, is self-taught. The rest of it was street sense. I don't got no book sense, because my parents weren't able to send me to school. My mom and dad were sharecroppers, we was sharecroppers.

Most people these days don't understand that part of the recent past. We don't get it.

I try to tell my grandchildren that now. I used to come home in the afternoon on that farm in Louisiana. My mother had boiled a potato; that's all she had. If I said, "Momma, I don't want that," she would make me take the glass of water and go to bed. I could see as I got old enough how frustrated she was because that's all she had for me to eat. And they was so happy when I was 10 or 12 years old, I could go out on my own in the off season and hunt rabbits, birds, whatever, to keep you from eating boiled potatoes or boiled beans, you know. Because back then, there wasn't no McDonald's or Burger King, man, trust me.

What was your favorite part of writing this book?

What was your favorite part of writing this book?

David is such a good guy, because it's like lighting a fire with a wet piece of wood. Some of the things in there would take me 10 years to remember, but if you remind me of it, it's there. So he could go back. He knew a lot of the history. I could still beat him out once in a while. You know some of the younger people made a hit out of these songs, other than the people that made them did in the '20s. He'd talk about one of these old songs, and I'd say, "Uh-uh, David, that's not the case, that was Harvey Jo Turner," or one of those guys no one knows about now and he would say, "You got it. You don't forget."

You know, I'm 76 years old this year, and when I was coming up, if you was a guitar player, you was one of a kind. You could count all the guitar players on one hand when I was coming up. Lonnie Johnson, Lightning Hopkins, and I think T-Bone, and then out popped B.B. King and John Lee Hooker. You used to go into the music shop and ask for a harmonica and the owner would say, "Just give me anything to get it out the way, man." But Little Walter said, "If George Washington Carver could get all that technology out of a peanut, then I guess I can get something out of a harmonica," and boy he didn't fail. B.B. King did the same for the guitar. Now harmonicas and guitars are expensive.

In the book you talk about all the British artists coming over and playing the blues. I'd think you'd be angry at them for it, but you're not.

How could I be? The British guys came back to America and told white America who B.B. King or Ike and Tina Turner was. I don't know if you're old enough to remember, but they had a television show back then called Shindig. The Stones was getting bigger than bubblegum, and they was trying to get the Stones to come on Shindig, and finally Mick Jagger said, "I'll do it if you let me bring Muddy Waters." And they say, "Who is that?" And he got offended, "You don't know who Muddy Waters is? We named ourselves off of one of his records, Rollin' Stone." Me and him laughed about that a couple of weeks ago at the White House when we played for the president.

What do you listen to now?

Well, I haven't changed a lot. A lot of people get successful and forget who they are, they forget where they come from, but guess what? We all was listening to spirituals and things before the guitars got amplified by Les Paul and Leo Fender and them. Lou Rawls had the Pilgrim Travelers, and I don't know if you can find that album, but I have it. I used to go pay 50 cents to go see the Pilgrim Travelers in Louisiana and it wasn't no drums or keyboards, it was just five or six guys making mouth noises behind the lead singer.

What about rap music and hip hop?

Well, [Shawnna] my youngest daughter--you probably know more about her than about me. She started out there with Ludacris, but is out on her own now. I guess she's been out there nine or 10 years. She's doing pretty good at it so far. You know, I don't have no complaint or nothing for what people like. Anything that people like that keeps them from fighting and fussing and shooting and cussing and doing like that.

After they stopped playing blues on the radio at all, I figured our lyrics were a little bit too strong. You hear B.B. King sing, "I got a sweet little angel, I love the way she spreads her wings," I was so dumb, I said, "B., what is that," and he said, "That's what we call beating around the bush, Buddy, you have to figure out what I meant."

Not any more, though.

No, the hip hoppers broke that up. You know the Isley Brothers had a record out in the '60s about some bulls**t going on, you had to bleep the "s**t." Now, you could come out and sing that, they'll probably have a double-platinum album that they'll sell you. You know, Johnny Guitar Watson played one, he didn't write it, but he had one 'bout "Dirty Mother for You." They would call that a party record. They wouldn't dare play that on the air.

Any regrets from your life?

No, I'd jump out the window to be able to do it again. Picking cotton in Louisiana is a long way from picking the guitar in the White House. --Rob LeFebvre, freelance writer and editor