|

|

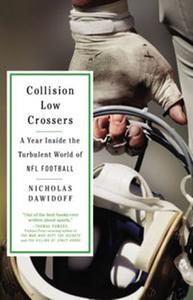

| photo: Koren-Angell Studios | |

Nicholas Dawidoff's Collision Low Crossers: A Year Inside the Turbulent World of NFL Football (Little, Brown, $29) is an engrossing, exciting book--a classic sports narrative. (And one of the books that President Obama bought on Saturday at Politics & Prose Bookstore in Washington, D.C., during his highly publicized shopping expedition with his daughters.) Dawidoff, Pulitzer Prize finalist for The Fly Swatter--a chronicle of the life of his grandfather, a Russian-born scholar--and a Branford Fellow at Yale University, spent 2011 with the New York Jets, and had unlimited access to the coaches, the players, the offices and locker rooms. He describes the draft, the strategy sessions, the Combine (disquietingly like a slave market), and the players and coaches. He offers indelible, incisive portraits of the Jets: charismatic head coach Rex Ryan, offensive and defensive coaches, struggling QB Mark Sanchez, canny safeties, quirky and excitable cornerbacks, eager rookies and players who don't make it.

Dawidoff's observations and understanding of what he saw are penetrating and sometimes surprising, like how much the coaches work--nearly 24/7. What makes Collision Low Crossers soar like a perfect pass is his prose. Equipment manager Vito Contento "had the world-weary manner of a person who had seen far too many reasonably intelligent men toss their dirty shirts into the towel bin"; John Connor "blocked like a crate of bourbon"; special teams-coordinator Mike Westhoff spoke "in staccato beats of snarl"; if outside linebacker Aaron Maybin was fit, "that dude was the full agitato. If he wasn't fit, they'd cut his a**, allegro"; a losing game had "burst like a pillow; there were feathers everywhere."

In 2011, the Jets thought that the Super Bowl was attainable, but "the season vaporized"--they were undone by player (and coach) tension, and a lack of understanding of that discontent by Ryan. Was there more?

The problems of morale that the Jets experienced were not atypical of those endured by other teams. What really undid the Jets were crucial injuries to three of the most intelligent defensive players on whose football acumen the workings of the sophisticated defensive scheme depended, and then there was the beguiling regression of the quarterback Mark Sanchez. He committed so many crucial turnovers and generated erratic scoring. Given the rules of today's NFL, which cant heavily in favor of quarterbacks, the QB better be good.

You write about the team having "a mutual sense of binding purpose" and the family feeling (sometimes dysfunctional) that a team creates, but all teams are "annual teardowns." What does that sort of whiplash do to a player?

More, what does it do to the coaches who are responsible for achieving that sense of unity among players? A chief purpose of the long, football-immersive NFL off-season is to create exactly that--to assimilate players and bond them to your coaching ideals and aspirations.

There is so much joy in football for the players and coaches, along with the misery of pain and defeat--"Football brought so many little deaths so early in life." You say that football is a game of process, and "the arrival [can] never be as meaningful as the approach." Is that the way to maintain one's sanity?

If your whole sense of self worth is bound up in winning or losing, you won't last long as an NFL coach. As competitive as NFL men are, it is their ability to absorb, understand and move past terrible public failure that defines them in the profession.

If you aren't a confident, optimistic person, you won't be a successful coach. Jets quarterbacks coach Matt Cavanaugh told me on the practice field one day when the Jets were 2-0 that I hadn't yet seen the NFL. I'd see it when things went badly, he said, because success among players and coaches depends on how people respond to harrowing adversity. The Jets soon had their opportunities in this regard.

Can you quantify what makes unified team? Winning certainly helps, but there must be more than winning. A lucky meshing of personalities?

Nobody knows. What distinguishes a good team from a poor one is the NFL's signal mystery. Any given team can win against any given opponent. The legendary coach Joe Gibbs told Rex Ryan that his every season with the Redskins was the process of learning how good his team was. Gibbs said that in August he never knew. That aside, winning teams generally have a reliable quarterback, good health and a stout, opportunistic defense that generates many turnovers. Turnovers are the most crucial events in football games aside, of course, from scoring.

You describe your year with the Jets as a long car trip with days blending into each other because they never stopped. It seems like football, more than other sports, is perpetual motion--conditioning, learning, dissecting--for everyone involved.

Yes, day-to-day the immersion is complete, meaning that the rest of life passes by nearly unacknowledged. Football men live in the perpetual thrall of process. All year they are creating football plans, trying to understand their team and their opponents. The games are 16 exceptions, the NFL holidays on which every man's reputation rests. Regular life in the NFL is preparation.

A cliché about football players is that they are physical beings, not intellectual. But after reading your book, I'd say that most football players are really intelligent--they memorize new plays, they dissect the tape, they make instant decisions and reads.

Football players are every kind of person. That said, some not especially "book-smart" players have great aptitude for understanding the game, and some who are wonderfully intelligent in conventional ways can't grasp football ideas at all. Football requires more study and off-field application than any other team sport that I know of. The facility is really a football university. The players are students; the coaches are their professors. The players even look the part--flip-flops, sweats and backpacks.

There is a team code, a "family" code--what happens in the locker room stays there. Is that what you think is going on with the Dolphins situation? At what point does something like this become unacceptable?

Former Jets players I know have said they can't imagine that happening in New York. The Dolphins' shameful incident is not typical, but such is the level of immersion in football that I can see how, almost casually, teasing might devolve into something terrible. Everybody knows when banter is affectionate or intended to express some kind of cruel power dynamic, and when it is the latter, the recipient comes to dread going to work. When all you do is work, that's a big problem. --Marilyn Dahl