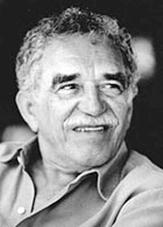

Colombian author Gabriel García Márquez, whose landmark novel One Hundred Years of Solitude "established him as a giant of 20th-century literature," died yesterday, the New York Times reported. He was 87. García Márquez, who received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1982, "was considered the supreme exponent, if not the creator, of the literary genre known as magic realism," the Times noted, though the author "made no claim to have invented magic realism; he pointed out that elements of it had appeared before in Latin American literature." His many books include The Autumn of the Patriarch, Chronicle of a Death Foretold, Love in the Time of Cholera and The General in his Labyrinth. One Hundred Years of Solitude contains one of the best opening lines in literature: "Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendía was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice."

Colombian author Gabriel García Márquez, whose landmark novel One Hundred Years of Solitude "established him as a giant of 20th-century literature," died yesterday, the New York Times reported. He was 87. García Márquez, who received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1982, "was considered the supreme exponent, if not the creator, of the literary genre known as magic realism," the Times noted, though the author "made no claim to have invented magic realism; he pointed out that elements of it had appeared before in Latin American literature." His many books include The Autumn of the Patriarch, Chronicle of a Death Foretold, Love in the Time of Cholera and The General in his Labyrinth. One Hundred Years of Solitude contains one of the best opening lines in literature: "Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendía was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice."

García Márquez's death "represents the passing of one of the world's greatest living authors, and the loss of a powerful public intellectual whose opinions on Cuba, military dictatorship and Latin American cultural autonomy made front-page news," the Los Angeles Times wrote, adding that the news of his death "was met with an outpouring of grief and reverence for the writer known to his admirers simply as 'Gabo,' and who was often compared to Hispanic literature's other titan, Don Quixote author Miguel de Cervantes. More than any other author, García Márquez fueled the post-World War II popularizing of Latin America literature known as the 'Boom.' "

"Being a contemporary of Gabo was like living in the time of Homer," said Colombian writer Hector Abad Faciolince, "In a mythic and poetic way, he explained our origins. His verbal imagination and creative force were astonishing."

In the Telegraph, Gaby Wood wrote: "The Colombian novelist Alvaro Mutis used to tell a story about his close friend and compatriot Gabriel García Márquez.... In the mid-Sixties, when the latter was writing One Hundred Years of Solitude (1967), they met every evening for a drink. García Márquez would tell Mutis about the scenes he'd written that day, and Mutis would listen, waiting avidly for the next installment. He started telling their friends that 'Gabo'--as García Márquez was affectionately known--was writing a book in which a man called X did Y, and so on. When the novel was published, however, it bore no relation to the story García Márquez had told over tequila--not the characters or the plot or any aspect at all. Mutis was left with the feeling of having been brilliantly duped, and he mourned the unwritten novel of the bar, that ephemeral fiction no one else would ever hear.

"It would have been a good anecdote no matter who the writers were, but it's particularly apt in the case of García Márquez, who could hold innumerable tales in his head, and spin them simultaneously. The oral novel offered to Mutis was a kind of enactment of the principle on which García Márquez's books were based: that what is passed down and told to you, however unbelievable, is part of your history; and that what we naively call lies can be far more true than facts."