More Top 10 lists from Shelf

Awareness folk... (see here for more).

Top Ten Books of 2010: Harvey

Freedenberg, reviewer

Freedom by Jonathan Franzen (Farrar, Straus & Giroux). While it's risky

to predict how the winds of literary fashion may blow someday, Franzen's novel

has all the earmarks of a work of enduring merit and significance. Its deep,

compelling portrayal of our uneasy times is matched by the acuity of Franzen's

insight into the souls of his troubled creations.

Freedom by Jonathan Franzen (Farrar, Straus & Giroux). While it's risky

to predict how the winds of literary fashion may blow someday, Franzen's novel

has all the earmarks of a work of enduring merit and significance. Its deep,

compelling portrayal of our uneasy times is matched by the acuity of Franzen's

insight into the souls of his troubled creations.

The Imperfectionists by Tom Rachman (The Dial Press). International

journalist Rachman supplies a satiric look at the newspaper business and much

more in his sly novel in stories about the travails of the staff struggling to

keep a small English-language paper afloat in Rome while wrestling with their

messy personal lives.

Memory Wall by Anthony Doerr (Scribner). Traversing settings from South Africa to

Wyoming to Lithuania to suburban Cleveland, and in time from the Holocaust to a

near-term dystopian future, in this outstanding short story collection Doerr

probes the subject of memory in evocative prose that only enhances the richness

of these consistently moving tales.

Super Sad True Love Story by Gary Shteyngart (Random House). It remains to be seen whether through

some combination of self-indulgence, profligacy and inattention America will

slide into the chaos Shteyngart channels in this brilliant satire. We have

something to say about that, he seems to be telling us. And we might do well to

take heed before it's too late.

Matterhorn by Karl Marlantes (Atlantic Monthly

Press, in association with El León Literary Arts). As ancient as The Iliad and as contemporary as the

latest dispatch from Afghanistan, stories of war will continue to absorb and

repel us. Marlantes's novel is a worthy addition to that body of literature,

rising above the particularities of the conflict it describes to achieve a firm

handhold on universal truth.

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot (Crown Publishers). In her first book, science journalist Skloot

uncovers the incredible story of Henrietta Lacks and the remarkable HeLa cells

that have spurred countless scientific advances, from polio vaccine to in vitro fertilization. While it's

hardly recompense for half a century of anguish, the Lacks family has attracted

a worthy chronicler of their amazing, often disturbing tale.

War by Sebastian Junger (Twelve). Junger offers an intense

account of his time embedded with the men of the Second Platoon of Battle

Company in Afghanistan. For those who haven't experienced combat and never will,

there's little to do but marvel at the courage of the men he describes and the

unflinching glimpse he offers us into their lives.

Making Toast by Roger Rosenblatt (Ecco). There

was a time when a brief account of the three generations of a close-knit family

living under the same roof and struggling to make sense of the sudden death of

a young wife and mother wouldn't have been all that extraordinary. That it

takes place within the last two years in an affluent household in Bethesda,

Md., transforms Rosenblatt's plainspoken, heartfelt story into something

remarkable.

Half a Life by Darin Strauss (McSweeney's

Books). Imagine yourself a few weeks

from your high school graduation, cruising down the road with a carload of your

friends. Now imagine the almost inconceivable: a fellow student riding her

bicycle swerves into the path of your car and is killed instantly. Novelist

Strauss was the driver of that car in May 1988 and this memoir is the intense, searching account of

the path he traveled from that grim day to the present.

Essays from the Nick of Time by Mark Slouka (Graywolf Press). Slouka, who teaches at the University of

Chicago, offers a dozen challenging meditations (several of which have been

selected previously for inclusion in the Best

American Essays series) located at what he calls "the intersection of

memory and history and fiction."

---

Top Ten Books of 2010: Robert Gray,

contributing editor

My list this year seems to have naturally lined up in pairs:

Fiction

Fiction

Matterhorn by Karl Marlantes (Atlantic Monthly Press). Like my Shelf colleague Marilyn Dahl, I had some reservations about reading another Vietnam novel. But this precisely detailed, evocative portrayal of hard-won survival and humanity in a combat zone turned out to be my favorite read of the year.

Up from the Blue by Susan Henderson (Harper Paperbacks). As I read this brilliant debut novel, I kept thinking that if I was still working on a bookstore sales floor, I could handsell a bunch (bookseller shorthand for dozens, maybe hundreds) of copies. "You have got to read this," I would say, like an incantation.

Travel

Travels in Siberia by Ian Frazier (FSG). As always, Frazier crafts a work of nonfiction that opens my eyes to a subject and a people I thought I knew something about. And how can anyone resist a book with observational gems like the fact that Lake Baikal "contains about 20% of the world's freshwater"?

Jeff in Venice, Death in Varanasi by Geoff Dyer (Vintage). Yes, it's technically a novel, but you also have to take into account the fact that Geoff Dyer is, well, Geoff Dyer, and the usual rules about any genre simply do not apply to him. There is magic in this tale and I was utterly spellbound.

Memoir-ish

Autobiography of Mark Twain, Vol. 1 (University of California Press). As many critics have pointed out, this isn't really a memoir. It's a collection of memories. Reading Twain's sharp-tongued reflections and sometimes rambling--but always illuminating--recollections is like listening to the greatest dinner conversation/monologue ever.

Hitch-22 by Christopher Hitchens (Twelve). This book is also not, strictly speaking, a memoir, but it does offer intriguing biographical details--later made more compelling with the revelation of his illness--mixed generously with fierce and brilliant opinions. Whether I agree or disagree with Hitchens on a particular subject, I still love to watch his mind at work and at play.

My Obsession with Silence

A Book of Silence by Sara Maitland (Counterpoint). This year I became intrigued with the concept of silence and its increasingly rare presence in our cacophonous world. Maitland writes a fiercely beautiful account of her attempt to pursue silence as a way of life, with all the complexities inherent in such an impossible, yet sometimes approachable, quest.

In Pursuit of Silence: Listening for Meaning in a World of Noise by George Prochnik (Doubleday). In contrast to Maitland's work, Prochnik explores a full range of sound and silence in human existence, noting, among many insightful observations, that we are are the only species--predator or prey--that seems compelled to consciously make so much noise as we move through the world.

Bookseller Recs

Comeback Love by Peter Golden (Staff Picks Press). I've written about the publication of Golden's novel in my column (Shelf Awareness, November 5, 2010). This book makes my list this year not only because it is a quality read that would be an easy handsell, but also because of its notable genesis as an indie bookseller-published work with national sales potential.

Merit Badges by Kevin Fenton (New Issues/Western Michigan University). At the MBA trade show in St Paul, Minn., this year, Martin Schmutterer of Common Good Books convinced me to read this novel and introduced me to the author. Thanks, Martin. Fenton's story is a beautifully crafted, perceptive and often funny evocation of some extraordinary, ordinary people.

---

Top Ten Books

of 2010: John McFarland, reviewer

Vile Bodies by Evelyn Waugh (1930; reprinted by

Back Bay Books). A romp through a fantastical 1920s London filled with

strivers, dimwits and vampy flappers that is guaranteed to make a dreary day

seem sunny and change your mood from dull to effervescent.

Vile Bodies by Evelyn Waugh (1930; reprinted by

Back Bay Books). A romp through a fantastical 1920s London filled with

strivers, dimwits and vampy flappers that is guaranteed to make a dreary day

seem sunny and change your mood from dull to effervescent.

The Judgment of Paris: The

Revolutionary Decade that Gave the World Impressionism by Ross King (Walker). The Paris art

world went from celebrating large historical canvases in shades of brown and

gray to those featuring riots of color in the decade that King covers so well.

Sample factoid: Manet couldn't give away his paintings (any one of which will

now cost you in excess of $45 million).

Loitering with Intent by Muriel Spark (New Directions). A

fraudulent academy purporting to help aspiring authors write their

autobiographies provides the setting for Muriel Spark to skewer snobbery and

stupidity in her most delicious, inimitable and eccentric manner.

A Gift for Admiration: Further

Memoirs by James

Lord (Farrar, Straus & Giroux). If you were friends with James Lord, you

might not have realized he was keeping a very precise and, as it turns out,

withering record of his encounters with you. Here, he delivers the goods on

Peggy Guggenheim, Sonia Orwell and Isabel Rawsthorne, among other fascinating

characters.

The Golden Mean: A Novel of

Aristotle and Alexander the Great

by Annabel Lyon (Knopf). A richly imagined and engrossing novel of fourth-century

B.C. Macedon and Greece in which Aristotle tells all, including entrancing

tales of his most famous student.

Claude Levi-Strauss: The Poet in the

Laboratory by

Patrick Wilcken (Penguin). A rich and satisfying intellectual biography of one

of the foremost thinkers of the 20th century, of special interest to

anthropologists and readers who thrilled to the discovery of Tristes

Tropiques.

Prayer for My Enemy by Craig Lucas (Theater

Communications Group, 2009). A work of theatrical genius--rich in character,

emotion, regret, possibility and tragedy--that covers the war in Iraq,

addiction, forbidden love and the eternal battle between the Yankees and the

Red Sox.

Old Goriot by Honore de Balzac, translated by

Marion Ayton Crawford (Penguin Classics). A ramshackle Parisian boarding house,

packed with some on the rise, others on the decline, is the scene of human

comedy at which Balzac excels.

The Summer People by Maxim Gorky, translated by Nicholas

Saunders and Frank Dwyer (Smith and Kraus, 1995). A delightful play by Maxim

Gorky in a Chekhovian mood yet wielding satire like a surgeon's scalpel at the

expense of the Russian bourgeoisie.

A Dead Man in Deptford by Anthony Burgess (Da Capo Press).

A brilliant novel about the tempestuous life of Christopher Marlowe, playwright

and spy, by a master of the English language who is also a supreme entertainer.

---

Top Ten of 2010: Ron Hogan, reviewer

A Little Bit Wild by Victoria Dahl (Zebra). Hands down the best

historical romance I read this year. A precocious young heroine whose

blossoming appetites have already gotten her into trouble, and the rough but

sincere bastard son of a duke who volunteers to pretend to be engaged to her,

served up with a delightfully saucy sense of humor.

A Little Bit Wild by Victoria Dahl (Zebra). Hands down the best

historical romance I read this year. A precocious young heroine whose

blossoming appetites have already gotten her into trouble, and the rough but

sincere bastard son of a duke who volunteers to pretend to be engaged to her,

served up with a delightfully saucy sense of humor.

For the Win

by Cory Doctorow (Tor). Doctorow's second YA book is one of the year's most politically

engaging novels at any level. A truly global perspective on the impact of the

new economies created through the Internet, and a gripping story about labor

activists struggling to organize tomorrow's outsourced workforces.

Lord of Misrule by Jaimy Gordon (McPherson & Co.). If there was

ever an appropriate time to say the dark horse took the National Book Award,

this would be it. But Gordon's story about the not-so-glamorous side of horse

racing has the potential to become an enduring noir classic.

A Friend of the Family by Lauren Grodstein (Algonquin). Pete

Dizinoff really didn't think the woman his son was getting involved with was

suitable, so he decided to do something about it. Grodstein's masterful prose

renders Pete's voice as he looks back on events, after everything has gone to

hell.

The Instructions by Adam Levin (McSweeney's). In this surreal, rambling

debut, a 10-year-old with counterinsurgency training leads his most troubled

classmates in a violent uprising. Oh, did I mention the boy might also be the

messiah? Yes, it's over 1,000 pages long; yes, it's worth it.

The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet by David Mitchell (Random House). Even

when David Mitchell decides to do a straightforward historical novel, it's

still as relentlessly inventive as all his other fiction. A young Dutch

merchant-in-training arrives in Nagasaki in 1799 and finds much more corruption

than he'd bargained on, but that's just the surface of the emotionally complex

world Mitchell creates.

Skippy Dies

by Paul Murray (Faber & Faber). I've been recommending this novel to anyone

and everyone since I read it at the end of the summer. It made me laugh, then

it made me cry, then it made me laugh all over again. It's simply brilliant.

So Much for That by Lionel Shriver (Harper). A domestic drama of

overwhelming resonance, as a Brooklyn contractor's life savings are depleted by

his wife's mesothelioma (not to mention his aging father's increasing need for

care). But Shriver doesn't indulge in a lot of sweeping literary passages about

what it all means; she just keeps pushing the story as hard as it will go.

The Tiger

by John Vaillant (Knopf). It's the one nonfiction title on my list, but it's a

doozy. A little over a decade ago, a tiger stalked the forests around a remote

Siberian settlement, killing any human that got in its way. Vaillant's

absorbing meditation on man's relationship to nature and the wild never loses

sight of the dramatic story of this beast's rampage and the hunt to bring him

down.

I Hotel

by Karen Tei Yamashita (Coffee House Press). There is no one Asian-American

story. But Yamashita's set of interlocking novellas goes a long way towards

depicting the turbulent development of

Asian-American identity through San Francisco's political and cultural

underground between 1968 and 1977. An amazing, kaleidoscopic 600-page epic that

deserves to be absorbed in one marathon sitting.

Laura Ayrey has been named executive director of the Mountains & Plains Independent Booksellers Association, effective December 20. She succeeds Lisa Knudsen, who is working with Ayrey to facilitate the transition by early January.

Laura Ayrey has been named executive director of the Mountains & Plains Independent Booksellers Association, effective December 20. She succeeds Lisa Knudsen, who is working with Ayrey to facilitate the transition by early January.

BookExpo America will remain in New York City for the foreseeable future, according to BEA show director Steve Rosato, who wrote on the

BookExpo America will remain in New York City for the foreseeable future, according to BEA show director Steve Rosato, who wrote on the  Early next year, bestselling author and entrepreneur Seth Godin will launch the

Early next year, bestselling author and entrepreneur Seth Godin will launch the  Jeff Bezos was profiled by

Jeff Bezos was profiled by  Amazon plans to build a distribution center in Cayce, S.C., that will have 1,250 full-time employees,

Amazon plans to build a distribution center in Cayce, S.C., that will have 1,250 full-time employees,

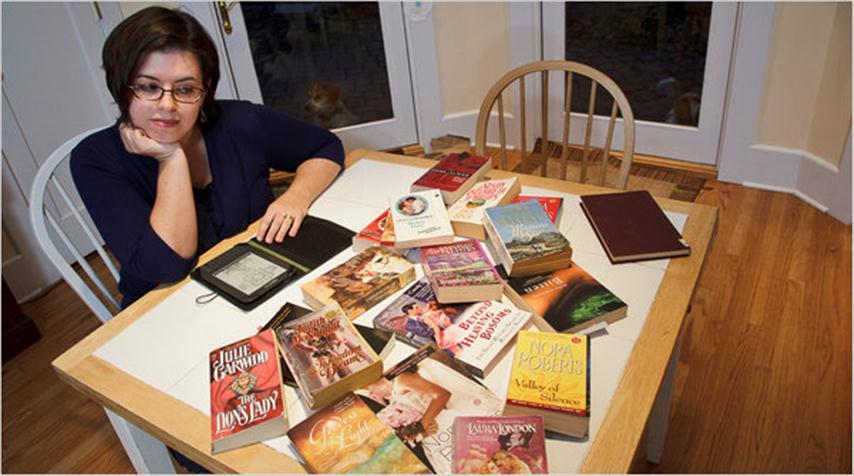

"If the e-reader is the digital equivalent of the brown-paper wrapper, the romance reader is a little like the Asian carp: insatiable and unstoppable. Together, it turns out, they are a perfect couple," the

"If the e-reader is the digital equivalent of the brown-paper wrapper, the romance reader is a little like the Asian carp: insatiable and unstoppable. Together, it turns out, they are a perfect couple," the  Yesterday morning,

Jason Ashlock, founder of Movable Type Literary Group, invited readers

of his

Yesterday morning,

Jason Ashlock, founder of Movable Type Literary Group, invited readers

of his  On Black Friday, the aptly named Book Store opened in downtown Loganville, Ga., the

On Black Friday, the aptly named Book Store opened in downtown Loganville, Ga., the  The generation gap: books and music category. From

The generation gap: books and music category. From

This year for holiday gifting Fassett

stocked up on coffee-table books, something customers aren't as likely to

be reading on electronic devices. One of her favorites is Horse by photographer and equestrian Kelly Klein. Books

with a regional slant are also popular selections, such as Canyon

Wilderness of the Southwest by Jon Ortner

and The Art of Maynard Dixon by

Donald J. Hagerty.

This year for holiday gifting Fassett

stocked up on coffee-table books, something customers aren't as likely to

be reading on electronic devices. One of her favorites is Horse by photographer and equestrian Kelly Klein. Books

with a regional slant are also popular selections, such as Canyon

Wilderness of the Southwest by Jon Ortner

and The Art of Maynard Dixon by

Donald J. Hagerty.

Cate Blanchett has been cast to play Galadriel in Peter Jackson's film version of J.R.R. Tolkien's The Hobbit.

Cate Blanchett has been cast to play Galadriel in Peter Jackson's film version of J.R.R. Tolkien's The Hobbit.  Freedom by Jonathan Franzen (Farrar, Straus & Giroux). While it's risky

to predict how the winds of literary fashion may blow someday, Franzen's novel

has all the earmarks of a work of enduring merit and significance. Its deep,

compelling portrayal of our uneasy times is matched by the acuity of Franzen's

insight into the souls of his troubled creations.

Freedom by Jonathan Franzen (Farrar, Straus & Giroux). While it's risky

to predict how the winds of literary fashion may blow someday, Franzen's novel

has all the earmarks of a work of enduring merit and significance. Its deep,

compelling portrayal of our uneasy times is matched by the acuity of Franzen's

insight into the souls of his troubled creations. Vile Bodies by Evelyn Waugh (1930; reprinted by

Back Bay Books). A romp through a fantastical 1920s London filled with

strivers, dimwits and vampy flappers that is guaranteed to make a dreary day

seem sunny and change your mood from dull to effervescent.

Vile Bodies by Evelyn Waugh (1930; reprinted by

Back Bay Books). A romp through a fantastical 1920s London filled with

strivers, dimwits and vampy flappers that is guaranteed to make a dreary day

seem sunny and change your mood from dull to effervescent.  A Little Bit Wild by Victoria Dahl (Zebra). Hands down the best

historical romance I read this year. A precocious young heroine whose

blossoming appetites have already gotten her into trouble, and the rough but

sincere bastard son of a duke who volunteers to pretend to be engaged to her,

served up with a delightfully saucy sense of humor.

A Little Bit Wild by Victoria Dahl (Zebra). Hands down the best

historical romance I read this year. A precocious young heroine whose

blossoming appetites have already gotten her into trouble, and the rough but

sincere bastard son of a duke who volunteers to pretend to be engaged to her,

served up with a delightfully saucy sense of humor. News reports confront us on a daily basis about deadly conflicts in Afghanistan, Iraq, Korea and elsewhere. Anxiety is widespread that any of these hotspots could spark a major war. Is that anxiety truly justified, Christopher Fettweis asks in his provocative analysis of current thinking (and heated debate) in university political science departments.

News reports confront us on a daily basis about deadly conflicts in Afghanistan, Iraq, Korea and elsewhere. Anxiety is widespread that any of these hotspots could spark a major war. Is that anxiety truly justified, Christopher Fettweis asks in his provocative analysis of current thinking (and heated debate) in university political science departments.