On September 11, 2001, Christopher Myers called his father

on the phone. "Dad, check out the television. A plane just flew into the

World Trade Center," he said. "Not to be outdone," Walter Dean

Myers recalls, "I said, 'I remember back in 1947, a plane flew into the

Empire State Building.' " But then the second plane hit. Two months

later, Myers was in London with his wife, Connie (Christopher's mother), when a

plane malfunctioned and crashed in Queens, N.Y. A group of Middle Eastern men

were on a London street, watching the crash on television through the window of

an appliance store, cheering because they believed it was an act of terror. The

author's complex reactions to these two events sent him on a journey to

rediscover what America means to him. Christopher Myers, as the artist, went on

an odyssey of his own. But as Christopher puts it, "To be honest, these

are conversations, we've been having since I was a kid." Here they let us

in on the conversation about how their paths converged in the majestic We Are America.

From your foreword,

it seems that this book grew from a place of great feeling. Did the first draft

come to you in a rush?

From your foreword,

it seems that this book grew from a place of great feeling. Did the first draft

come to you in a rush?

Walter Dean Myers: No,

it did not. I started with a very

formal, very strict rhythm. I thought, "It's not working for me. I should

just write it as I feel it and see what happens," and I did a moderately

fast first draft. Then I looked at some of my lines, and I realized I was

paraphrasing. So I began looking at the originals. Then I thought, "This

guy said it better than I did." Sometimes it was better because the language

was more direct. It was so charged with emotion under the original

circumstances. I began to make a concerted effort to incorporate them. Then I

said, "No, take them out of my material because it's necessary to put

these things into context." That gave me a lot of freedom. I could write

the way I felt, have these quotations on the side, and hope that my editor

would go for it.

As you went through

those original documents, how did you decide which quotes to use in the poem?

WDM: Sometimes I'd

find, while looking through a speech, something I hadn't put in the book, and

think, "let me go and mention this." I hadn't read a lot of it since

I was in high school. They were so stirring and to the point. You also find

people serving their own purposes, twisting things--twisting Lincoln, twisting

Jefferson. It's a damn shame that Jefferson is known to many people only by the

fact that he might have had an affair with Sally Hemings.

Christopher Myers:

What's also odd about the way people think about these Founding Fathers, is

they think about them as people who lived without conflict, who lived as these

unified thinkers. That takes away from the strength of what it means to be

American. In fact, these guys were debaters, they were thinkers. That's the beauty

of this place, that it was founded on the idea of, "Let's make changes,

let's discuss." There's the Federalist Papers, but you look even in the

work of Jefferson, there's tumult. This is not a country about stasis, this is

a country based on tumult. And how does one deal with that?

WDM: That's a

good point. You don't make a lot of good points.

CM: Once in a

blue moon.

Was Walt Whitman an

influence for this piece? I thought of "I Hear America Singing" with

its hymn to the satisfaction to be gained from one's work, and also "One

Song, America, Before I Go."

WDM: I've always

been moved by Whitman. He is, to me, America's greatest poet. It's not a poetry of detachment, it's not a

poetry of abstraction. It's a poetry of love. I was very much conscious of his

influence.

Then there are the

ongoing themes of liberty and captivity throughout the poem. These kinds of paradoxes

are still with us, aren't they?

CM: That for me

is part of what I love about this place, is that we are able to acknowledge and

to think about our history. I travel a lot, [and in] other places, they work

very hard to have a very short memory of their countries--"We sprung up

out of nowhere whenever the last regime started." One of the gifts of this

place is we can think about and openly acknowledge and openly debate and

discuss our history. It's not that I'd ever look at this country and say

nothing bad ever happened. I'm the product of some of that bad that has

happened, slavery being the emblematic one. At the same time, there are very

few places in the world that can be so self-corrective.

WDM: One of the

things, talking about slavery, this is a country that brought an end to slavery

around the world. American debate brought an end to slavery. It was the

American Civil War that brought an end to slavery around the world. England

followed us; we did not follow England. As C.L.R. James said, they didn't need

slaves in England to do the work, so they could abolish it by keeping it in the

islands. Then they didn't need it in the islands because they had already a

virtually captive workplace. Although the British abolished slavery before

America, it was the American debate that caused that, in my view. Americans

talked about ending the powers of slavery more openly and more widely than

anyone in the world--that idea of freedom of speech, the idea of debating, the

idea of open conversation, it's still so great.

CM: When you ask

yourself, "What is America?" there are a lot of definitions. As much

as America is the people and the geography, America is also a set of ideas that

are very beautiful ideas, a lot of them. That was a big challenge of this book,

to contain all those definitions of America, to contain the people, the land,

the history, and the ideas. I would put ideas last.

WDM: I'll put

ideas first, just to be different.

CM: That's cool.

Rewriting runs thick in this family.

For the spread that

begins "Like clumsy children/ we fell/ as we learned to run," would

you call the references to Wounded Knee and Chapultepec Castle early examples

of the kind of present-day jingoism to which you refer in your foreword?

WDM: We have a

constant struggle in America. The people who want to achieve power will often

address that achievement as patriotism. It's no coincidence that the people who

portrayed themselves as the most patriotic are also the ones with the most guns--with

the most threats, either veiled or unveiled. The build to power is so great, so

fantastic, but what these people are doing is they are saying, "Well, this

power is not just me, it's my love of country." When you go into the

history of the country and who stood up for the country, who fought for the

country, who worked for the country, it's never these people. It's always small

people who saw a sense of duty and did it.

CM: We've talked

about these things since the inception of this country. That is what our

history gives us. Hopefully this book is a tool for a young child or

middle-schooler or an adult who would read the book with a child, to start them

on a journey to discovering their own America. As Dad says, it's the people who

have come in from the side--the immigrants, the poor, the women--who have found

ways to make this country better.

Is that, in part,

what informed your decisions about which individuals to include in your

paintings?

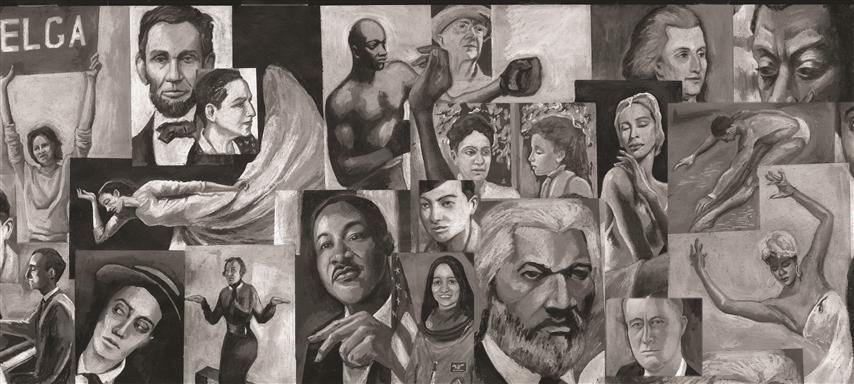

CM: There were

several things going on in my election of Americans. I wanted to think about

Americans that were unsung--Americans that did something to change the way

Americans were viewed both at home and abroad. There are some wonderful lines

about the landscape of America that Dad had written. What's amazing about

America is how the diversity of the landscape mirrors the diversity of the

people. You take, for example, Duke Kahanamoku, who's known as the father of

modern surfing, a Hawaiian guy. Here he is, a tall dark brown man who lived in

the water and represented the U.S. in swimming events in five Olympics. He went

around the world, spreading surfing and spreading the good will that he'd grown

up with in Hawaii. The idea of what an American was changed. He changed it--as

did all of the people that I elected after many debates along the way. To be

honest, that's all of our jobs in some way. Sometimes I travel in Asia; I was

recently in Sudan. You tell people, "I'm an American." Certain places

they look at you with incredulity. They say, "Americans look like this,

Americans look like that." You want to say, "No, Americans look like

me."

WDM: That

happened to us in a village in Egypt, a guy looked at us and asked, "Who

are you people?" We said, "Americans." They didn't want to

accept us. They accepted Connie [who has fair skin] as an American but not me.

CM: People have

this idea of Americans as being all blond-haired, blue-eyed cowboys or

raven-haired socialites. Whatever the latest television show is. I'm always a

bit taken aback. That was one of the things I wanted to talk about in the book

visually. There are different classes, races, different articulations of self

that are all equally American in the fact that they couldn't exist anywhere

else.

So many of the images

take on a mural-like quality. I thought of the WPA project murals. Did they

evolve into layered works? Did you do a lot of sketches first?

CM: One of the

chief influences of the art in the book is the Mexican muralists and the

muralists of the WPA. There's a lot of cross-pollination between them, everyone

from Aaron Douglas to Thomas Hart Benton, who did these WPA murals that tried

to wrangle entire histories of countries and entire intellectual trajectories.

The hard part is doing something that can match the anthemic and

all-encompassing tone of the text, as well as--Dad talked about Whitman's

quality of love. Love is big, love is open, especially the love that I have for

my country. The strategy of muralists, and of people who want to tell this

layered, rich history, is to add richness in that layering. Not one of the

pieces would work without that layering. That being said, there were a lot of

preparatory sketches, a lot of internal debate.

The paintings themselves

were 9' x 3', weren't they? Did you just lay them all around your studio and live

inside them?

CM: About 9' x 3',

yes. They took up a lot of space in my studio. And yes, pretty much, that's

what I did for months on end, with occasional phone calls from Phoebe [Yeh],

our editor. She'd say, "So how's it going?" And I'd say, "Right

now I'm sleeping in the sky that is being trod upon by a Mohawk skyscraper

worker in the 1940s." For me, it felt like taking a thousand mice and trying

to hook them up to a chariot.

WDM: And making

promises left and right, "Don't worry, Dad, it's coming soon."

Your images often

point out a paradox when laid out against the text, such as the image for "We

were willing to die/ to forge our dream," where you show the violent

response to the peaceful civil rights demonstrations against the founding

fathers' words, then you also join that together with the colonists risking

their lives to resist King George III.

CM: For me, that

spread is about seeing our country as being a country in which the history of

debate and protest are central. People try to take away the through line,

often. They want to say that my debate was different than your debate; my

struggle for rights was different than your struggle for rights. When in fact,

you're still coming back to the same amazing, beautiful, brilliant and flexible

and open documents. You're saying, look, through these documents, let me assert

my right for humanity. It's important to remind ourselves that the Civil Rights

movement was in some ways the realization of the independence dreams that were

had in the 1700s, to see those through lines, to lengthen our concept of

history. I tried to focus on Americans whose speech was important, who spoke

with their art, who spoke with their words, with their statesmanship, with

their science. This is not a country that tells people that they need to be

quiet. This is a country that says, "What do you have to say? We want to

know."

Your first

picture-book collaboration was Harlem

in 1997. In what ways was it different to work on this book, or does it feel

like part of a continuum?

WDM: For me, it

felt like a continuum, because I think what you do with literature is you

define yourself, and you define your place. How I know who I am is how I define

the world around me. I took Christopher to Harlem as a kid, and showed him all

the places I triumphed. [Laughs.] I think he understood how I was defining

Harlem; he took it from there. As we talk about this idea of America, I'm

listening to the conversations that we're having now. You mentioned

Chapultepec, and Christopher and I were there, and defining that, and defining

ourselves in Egypt, and defining ourselves in London [where I live] five weeks

a year. So we're constantly defining ourselves and discussing it. I see it as a

continuum. What do you think, Chris?

CM: I absolutely

see it as a continuum, but specifically because--we talk about Harlem and the

United States as geographic spaces, but more than geographic spaces, they're

conceptual spaces. They're places you write songs about. This is our song.

Harlem is a conceptual place, Harlem is a place I look to both as a home, and

as an exemplar of an artistic moment and a cultural moment that very strongly

relates to me. Similarly, in a larger way, America is a conceptual place. There

is a song that is there to be sung about diversity, about ideals, about hope,

about dreaming. We're both, I think, very excited to have added our voices to

the chorus.

Photo: Malin Fezehal

From your foreword,

it seems that this book grew from a place of great feeling. Did the first draft

come to you in a rush?

From your foreword,

it seems that this book grew from a place of great feeling. Did the first draft

come to you in a rush?

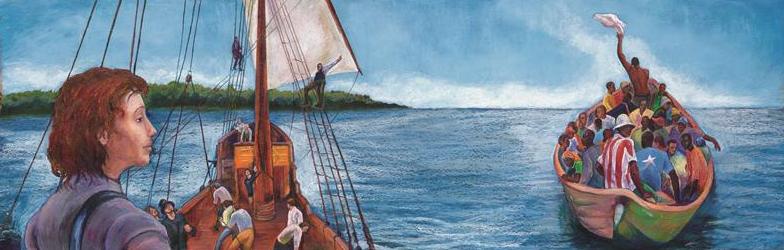

After Myers sent We

Are America to Yeh, she called him the next day and told him, "I'm

thinking this is for Chris to illustrate." She believed that Christopher

Myers had the "intellectual curiosity" to meet the challenge of the

text. It took him three years to illustrate the project. "When you see the

book, it makes perfect sense," said Yeh. "He had to come up with the

entire visual landscape for every spread. There was so much content. With [the

poem's] reference to the boats, for example, people would have expected

Christopher Columbus, and he showed John Smith." Around year two, Yeh got

to see a sample of the artwork--nine feet wide. "We

got nervous because we thought, 'We've never shot a book like this. How are we

going to do it? Where's the type going to go?" Martha Rago, the designer,

had to come up with a layout that would integrate long, flowing lines of

poetry, the quotes from the original documents and expansive horizontal artwork.

The art vignettes were Christopher Myers's idea. "I want kids to focus and

to look closely," he told Yeh. He felt that pulling out a detail from the

artwork would help them do that. He also suggested the classical typeface.

After Myers sent We

Are America to Yeh, she called him the next day and told him, "I'm

thinking this is for Chris to illustrate." She believed that Christopher

Myers had the "intellectual curiosity" to meet the challenge of the

text. It took him three years to illustrate the project. "When you see the

book, it makes perfect sense," said Yeh. "He had to come up with the

entire visual landscape for every spread. There was so much content. With [the

poem's] reference to the boats, for example, people would have expected

Christopher Columbus, and he showed John Smith." Around year two, Yeh got

to see a sample of the artwork--nine feet wide. "We

got nervous because we thought, 'We've never shot a book like this. How are we

going to do it? Where's the type going to go?" Martha Rago, the designer,

had to come up with a layout that would integrate long, flowing lines of

poetry, the quotes from the original documents and expansive horizontal artwork.

The art vignettes were Christopher Myers's idea. "I want kids to focus and

to look closely," he told Yeh. He felt that pulling out a detail from the

artwork would help them do that. He also suggested the classical typeface. On your nightstand

now:

On your nightstand

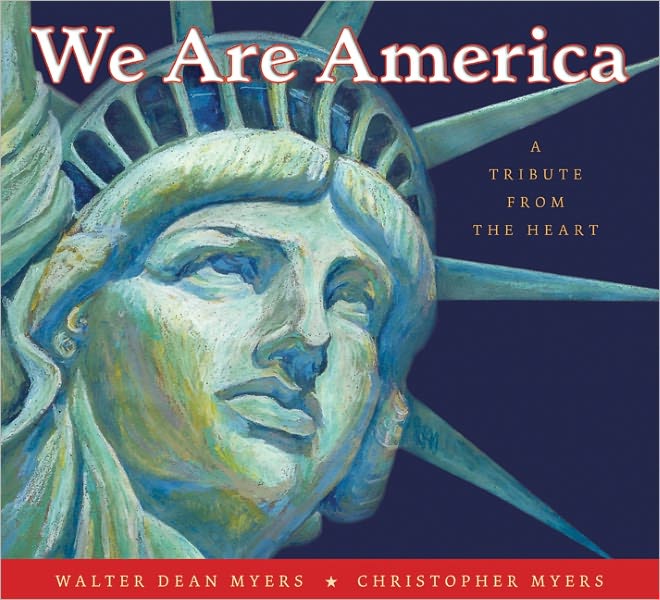

now: This glorious picture book by the father-son team that created Harlem immerses us deep inside the United States of America--its geography, its character, its ideas, its people. The close-up cover portrait of Lady Liberty suggests both untold strength and centuries of bearing witness to the "huddled masses" who have arrived on her shores. Author and artist ask us to reconsider icons such as the flag, the military uniform, and words and phrases we say from memory--the Declaration of Independence, the Pledge of Allegiance--and to ponder their deeper implications. What does it mean to be an American? What does America mean to you?

This glorious picture book by the father-son team that created Harlem immerses us deep inside the United States of America--its geography, its character, its ideas, its people. The close-up cover portrait of Lady Liberty suggests both untold strength and centuries of bearing witness to the "huddled masses" who have arrived on her shores. Author and artist ask us to reconsider icons such as the flag, the military uniform, and words and phrases we say from memory--the Declaration of Independence, the Pledge of Allegiance--and to ponder their deeper implications. What does it mean to be an American? What does America mean to you?