What were the seeds

for The Art of Racing in the Rain?

What were the seeds

for The Art of Racing in the Rain?

I used to make documentary films, and a friend asked me to

look at a film called State of Dogs.

It was about this belief in Mongolia that the next life for dogs would be as a

person. I kept thinking, "I wish I could do something with that, but how

do you do that?" It wasn't until I saw the poet Billy Collins who read his

poem from the point of view of a dog that's been euthanized that I thought, "That's

it! That story can only be told from the dog's point of view."

I raced for about four years as an amateur in a Miata and

had a great time doing it. I'm too competitive to be a middle-of-the-pack guy.

If you want to be good at racing, you have to put in all your time, energy and

effort, and I wasn't willing to do that. The zebra got in the car with me. If I'd

been able to say, "Look in the mirror: Is this where you want to be?"

I might have stopped. We get wrapped up in our passions, and sometimes the only

way to get out of it is to crash.

What made you want to

adapt The Art of Racing in the Rain

for a younger audience?

I have three kids, 14, 12 and four. When the book came out

in 2008, my 14-year-old was 11. The book was at Starbucks and stuff, and people

at school were talking about it. My son wanted to read it. I said, "Okay,

but there are some mature subjects in there. Let's keep tabs on it, and we'll

work through it together." That was great, and I thought, okay, an

11-year-old can read this along with a parent who's willing to work through it

with them. I realized that not all kids have a parent who's willing to do that.

There was bad language in the book, and the way I'd constructed the plot was

too mature for kids. I talked to my editor at Harper, and she said, "I

talked with the people at Harper Children's and they would love to work with

you on an adaptation that would do what you'd want it to do." Young people

identify with Enzo because they feel his frustration in essential ways. [They]

are essentially dogs, metaphorically speaking, in that they have fully

functioning, very intelligent brains--more intelligent than a lot of adults who've

forgotten too much. They have to ask for stuff, for clothes, to go places. The

tweens can get a charge out of Enzo, and take some of the same messages into

account: self-responsibility, self-reliance. The morals he puts out would

resonate with tween readers.

Enzo's relationship

with Zoë's zebra is fascinating as a measurement of his maturity and change in

perspective. Youngest readers might even believe the zebra is possessed in that first episode. How did the zebra develop as a

subtheme?

Enzo's relationship

with Zoë's zebra is fascinating as a measurement of his maturity and change in

perspective. Youngest readers might even believe the zebra is possessed in that first episode. How did the zebra develop as a

subtheme?

The true story behind that is this: I didn't know about the

zebra before I started writing the book. Sometimes I'll give myself a writing

assignment in the middle of a book because I need to know more about the

characters. It might not stay in the book, but it helps me explore. One day I

went into my office and thought, "I want to see what makes Enzo tick. I'm

going to lock him into the house for three days." Right away he finds the

toilet bowl so he won't go thirsty. He knows the food is right behind that

door, but he can't open the door. If you leave a dog with complete freedom for

several days, something will get destroyed. I don't think the dog wants to, I

think it happens--he would never do anything to hurt Zoë or her stuffed

animals. The zebra destroys itself, too, and leaves him framed for the job. I

read the scene over, and thought, "That's going to work!" I went

through the outline and thought, "Where else can I use the zebra?"

Including the climactic scene [where Denny's about to sign some crucial legal

papers]. We all have a zebra. It's the part where we don't want to take

responsibility for our own actions--a force beyond our control. Enzo's lesson

is: We are the zebra, and we have to acknowledge that, and when we do, we

render the zebra powerless.

The red pepper scene

(in which Enzo intentionally causes his own stomach upset) and Enzo's notion of

"King Karma" are so great in terms of Enzo being able to exact

revenge on the Twins in his own way.

It's interesting because that [red pepper] scene is tied in

with the zebra. Right after that scene, he goes in and growls at the zebra [in

Zoë's bedroom]. In a sense, that's a big transition moment. He's using the

tools he has available, and he's going to express his dissatisfaction. He's

standing up for himself and taking charge of his zebra. Crapping on the rug is

kind of a key moment for him.

Enzo is not an unbiased narrator. He's very opinionated. And

he's very possessive of his family. The demonization of the Twins is through

Enzo's eyes. Adult readers who I come in contact with forget that. I would dare

say the Twins probably aren't that evil, but they're evil in Enzo's eyes. If we

saw it through a different perspective, like an omniscient narrator, perhaps we'd

see them differently. They're wrong, they shouldn't be doing what they're

doing, but they want the best for their granddaughter. They're incorrect in

their assessment, but we run into that in the world all the time. I don't

believe that politicians whom I disagree with want evil in the world; they

differ in their opinion in how things should get done.

Denny has a lot of

compassion. He has to have compassion when he presents her grandparents to Zoë

in the best light. He also has to have compassion in that key scene with Zoë's

grandmother. And then there's the compassion that the head of Ferrari shows to

Denny. Does that have to do with karma, too?

Denny has a lot of

compassion. He has to have compassion when he presents her grandparents to Zoë

in the best light. He also has to have compassion in that key scene with Zoë's

grandmother. And then there's the compassion that the head of Ferrari shows to

Denny. Does that have to do with karma, too?

Yes. Absolutely. The deal with writing is this: I don't get

to control much, but it's a conversation between the reader and the writer.

People will ask me what message I want them to take away. It's presumptuous of

me to suggest what that is. If they want to put the book down and say that was

great entertainment, that's fine. But there are things I put in for a reason.

If you want to dig deeper, you can uncover these things.

The idea of listening without interrupting. When I was in

fourth grade, I had a teacher who said, "When someone else is speaking,

you can't raise your hand. If you're raising your hand, you're thinking about

what you want to say while they're speaking, and you're not listening." It's

fundamental to our society, and sometimes it's lacking. I'm going to listen,

think about it and then respond.

Denny's perseverance, being patient. Going to the driving

metaphor, if you're behind in a race and there are five or eight laps left to

go, the worst thing you can do is force the issue. You're taking the focus away

from where it should be. Look for your opportunities, and when it appears, you

have to take it. That's what Denny does with Trish [the grandmother] on the

street. The reason it works is because Enzo is his alter ego. They're each

other's yin and yang. Denny's got perseverance; he's balanced, he's looking for

the moment. Enzo wants to take Zoë and go to Canada. He thinks, "I really

wanted to take a couple of his fingers" when Maxwell [the grandfather]

hands him the red pepper. He voices the impulses that we feel, too: "This

is not right, somebody do something!" We identify more strongly with Enzo.

Then we learn the lesson of the book, which is we must approach our lives with

balance and patience, and we should not force issues that shouldn't be forced.

If we can do that, we will win the race.

Do you think we get

to choose when we die?

Enzo phrases it my "will to die." People talk about

a will to live but rarely a will to die. I do think, on some level, we can be

in control of that. I don't think everybody is in control of it. It's probably

not easy. But I do think there's a lot more that we can be in control of than

we give ourselves credit for, including our own healing and our own sicknesses.

A lot of times you get that cold or flu in the middle of extreme stress. You

could say your body is more susceptible. It might be your body saying, "If

I don't do this, you're going to have an aneurysm." We tend to look at

these things as victims, and I don't think we have to. This is the whole idea

of the zebra again.

That's the kind of stuff I want to work with in my writing.

I believe in the transformative power of fiction. As a writer I have to strive

to transform people--you have to put in a lot of effort to read a book, and

make pictures in your head that work. If you're going to put in the time, I

want you to walk away with some thoughts and ideas that will stay with you.

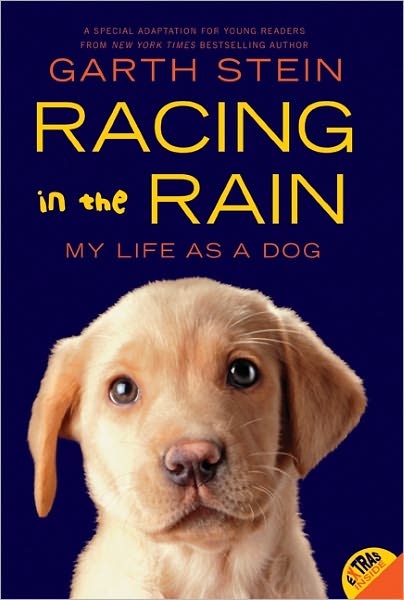

Why do a young reader's edition of the popular adult title The Art of Racing in the Rain (2008)?

Because every child has some of Enzo, a

charming lab-terrier mix, in him (or her). With a few adjustments (a slight

simplification of vocabulary and syntax, and a reworking of some adult themes),

Garth Stein has provided a version of his book that you may hand to any child.

Enzo, the wise and observant canine narrator, has advantages and disadvantages.

One of the chief advantages is access. People--adults--say things in front of

him they wouldn't say in front of others. So Enzo is privy to conversations and

information that Denny, his owner, is not. He has nearly full access to the

human world, yet, as a canine, he also possesses highly attuned senses. He can

smell where Denny has been all day and what he has eaten. He feels the mist of

the Seattle skies and the squish of mud beneath his paws, and he can read body

language and facial expressions like a secret code. He is fully in the moment--as

are children.

Why do a young reader's edition of the popular adult title The Art of Racing in the Rain (2008)?

Because every child has some of Enzo, a

charming lab-terrier mix, in him (or her). With a few adjustments (a slight

simplification of vocabulary and syntax, and a reworking of some adult themes),

Garth Stein has provided a version of his book that you may hand to any child.

Enzo, the wise and observant canine narrator, has advantages and disadvantages.

One of the chief advantages is access. People--adults--say things in front of

him they wouldn't say in front of others. So Enzo is privy to conversations and

information that Denny, his owner, is not. He has nearly full access to the

human world, yet, as a canine, he also possesses highly attuned senses. He can

smell where Denny has been all day and what he has eaten. He feels the mist of

the Seattle skies and the squish of mud beneath his paws, and he can read body

language and facial expressions like a secret code. He is fully in the moment--as

are children.

What were the seeds

for The Art of Racing in the Rain?

What were the seeds

for The Art of Racing in the Rain?  Enzo's relationship

with Zoë's zebra is fascinating as a measurement of his maturity and change in

perspective. Youngest readers might even believe the zebra is possessed in that first episode. How did the zebra develop as a

subtheme?

Enzo's relationship

with Zoë's zebra is fascinating as a measurement of his maturity and change in

perspective. Youngest readers might even believe the zebra is possessed in that first episode. How did the zebra develop as a

subtheme? Denny has a lot of

compassion. He has to have compassion when he presents her grandparents to Zoë

in the best light. He also has to have compassion in that key scene with Zoë's

grandmother. And then there's the compassion that the head of Ferrari shows to

Denny. Does that have to do with karma, too?

Denny has a lot of

compassion. He has to have compassion when he presents her grandparents to Zoë

in the best light. He also has to have compassion in that key scene with Zoë's

grandmother. And then there's the compassion that the head of Ferrari shows to

Denny. Does that have to do with karma, too? younger readers, she agreed. Day said, "It had a poignancy and a humor,

and a message of hope that we felt translated to young readers in the same way."

She believed that children could relate to Enzo's perspective, observing what's

unsaid and picking up on body language. To emphasize that identification, Day

said they wanted to bring Denny and Eve's young daughter, Zoë, more to the

forefront in this edition, and emphasize the relationship between them.

younger readers, she agreed. Day said, "It had a poignancy and a humor,

and a message of hope that we felt translated to young readers in the same way."

She believed that children could relate to Enzo's perspective, observing what's

unsaid and picking up on body language. To emphasize that identification, Day

said they wanted to bring Denny and Eve's young daughter, Zoë, more to the

forefront in this edition, and emphasize the relationship between them.  On your nightstand

now:

On your nightstand

now: