How did you first become interested in the lineage of Alexander the Great right through Cleopatra Selene?

How did you first become interested in the lineage of Alexander the Great right through Cleopatra Selene?

I was always a history buff, and around the time Oliver Stone was working on Alexander, my brother [Michael Alvear] got a call to work on a book about Alexander the Great. He asked me to help him with it, and I delved into the research. I'd tell my kids stories about Alexander the Great, and they were fascinated. I said--without knowing how difficult it was--that I would publish a children's book about him, and began working on it.

And Cleopatra was the next logical choice?

I learned so much about Cleopatra, but nothing shocked me as much as knowing she had four children, only one of whom survived into adulthood. I was fascinated by what a fierce mother she was. When you see Hollywood movies or plays about Cleopatra, it's always shown that she committed suicide after Marc Antony was brought to her. But the truth was, she lived for weeks after Marc Antony died, negotiating for the lives of her children. In fact, Plutarch writes that Octavianus attacked Cleopatra with threats to her children as if with "a siege engine." So her children were her weakness. Did she love Marc Antony? I believe she did. But this is where Octavianus attacked her. Plutarch says later that her son Caesarion was murdered. When all was lost, that's when she gives up hope. Now her suicide makes more sense.

You're so careful to delineate what is factual and what is not, even as you list the cast of characters. Is that because you hope people will seek out more information about these people?

That's exactly what I would hope. The history writer in me wants to convey to whoever reads it that this history is so rich, so fascinating, and there's so much to learn about these people and their politics, religion,and the interaction between rich and poor, male and female. Octavianus's slow dismantling of civil liberties in the name of safety is very much what we're struggling with today. The Romans were so tired of civil war, they didn't care [about their civil liberties] as long as there was peace. Female autonomy and all those things are still at issue today. In many ways, things haven't changed, and we can look at history as a mirror. How did that work out? On the one hand, it worked out great because [Romans] were the center of the world, but in the case of civil liberties, not so much.

Were there differences in your approach, given that this is a work of fiction, and you'd worked on nonfiction in the past?

I have to say right now, all I want to do is write fiction. It was very freeing. The only sources we have were written by Cleopatra's enemies. With fiction, that gave me the freedom to say, "Wait a minute." Plutarch said Cleopatra tested poison on slaves. Remember that it's coming from a Roman who needs to look good and make Cleopatra look bad; this was a war Octavianus started with Marc Antony and blamed on Queen Cleopatra. The fact of what Plutarch said was there. But what if there was a different reason for that? In protecting her children, she would make the potential poisoner take his own poison. As long as it's consistent with the essential facts, it allows me to shift the perspective a little bit and wonder, "What if it was in service of a different reason?"

The scene in the Jewish Quarter is crucial, in the way it demonstrates the queen's compassion for others' ways of practicing faith, but also because the rabbi introduces Cleopatra Selene to the idea of free will.

Outside of Jerusalem, Alexandria had the largest concentration of Jews during this period. Whatever Cleopatra's particular arrangement was, it was working for everybody. The idea of people wrestling with free will didn't just come up. Christianity took hold because of the suffering under the Roman Empire. And Cleopatra Selene is suffering. It made sense to me that this would be an idea she'd be introduced to and would struggle with. We're talking 25BCE, 30BCE, that's just one generation away from the birth of one particular figure--if we accept the dates that were given to us--who also will change the world.

Related to the idea of free will is that wonderful moment when Juba tells Cleopatra Selene, "The important question is not 'why was I saved?' but 'what will I do with the life that the gods decided to spare?'"

I think that is the essential question of philosophy, really. How much do we control? How much do we have, in terms of free will? How much is out of our hands? And young adults are grappling with those questions. I thought it was important for Juba to show this irony, that he was very much like her. He was taken. He was a prince. How did he handle it? Cleopatra Selene has changed Juba, because of the questions she asks him about the choices he's made. In my interpretation, that changes his character in the same way that she changes. That's what fiction allows. There are other interpretations that people can and have made. This is one that made sense to me and fits within the facts we know.

How did you come up with the structure of the novel, beginning with Cleopatra Selene's journey to an uncertain destination by ship, and then going back in time to fill in the major events of her life?

It was a challenge because I didn't want to lose the drama of the story--that some really incredibly horrible things happened to this young woman. It made sense to me that she'd ask herself, how did I go from the daughter of the most powerful woman in Egypt to this? Once I asked that question, I never really changed the structure. And that's what leads her to her decision, whether to be like her mother or to separate from her. It was important for us to see everything she's lost, for us to care about what choices she makes.

Author photo: Keiko Guest

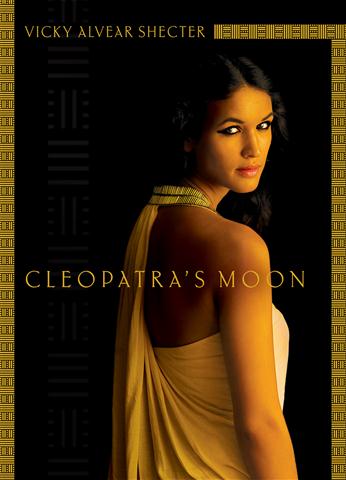

First-time novelist Vicky Alvear Shecter plunges us into the captivating world of Cleopatra Selene, the only one of Queen Cleopatra's four children (the other three were males) to survive into adulthood. It may surprise you to learn that Queen Cleopatra not only possessed a hypnotic beauty and keen intelligence, but that she was also a mother. Shecter may imagine the thoughts of Queen Cleopatra's extraordinary daughter, but the author anchors this riveting work of fiction with fascinating facts gleaned from years of research (for her nonfiction books Alexander the Great Rocks the World and Cleopatra Rules!).

First-time novelist Vicky Alvear Shecter plunges us into the captivating world of Cleopatra Selene, the only one of Queen Cleopatra's four children (the other three were males) to survive into adulthood. It may surprise you to learn that Queen Cleopatra not only possessed a hypnotic beauty and keen intelligence, but that she was also a mother. Shecter may imagine the thoughts of Queen Cleopatra's extraordinary daughter, but the author anchors this riveting work of fiction with fascinating facts gleaned from years of research (for her nonfiction books Alexander the Great Rocks the World and Cleopatra Rules!). We also see lighter moments--Cleopatra Selene's proficiency at the game of trigon ("I have beaten the king of Egypt," she says, teasing Caesarion) and her jealousy when her brothers receive Eye of Horus gifts from their mother, not realizing the significance of her own gift (a golden scarab pendant with an emerald in the center). These endow the weightier moments with greater significance. In one standout scene, the children's tutor, Euphronius, takes them to visit the Jewish Quarter in Alexandria. As their teacher explains, the queen "does not force them to act against their faith, thus earning their devotion and allegiance." They meet Rabbi Yoseph ben Zakkai, who encourages their questions, and Cleopatra Selene discovers the concept of "free will." The rabbi explains, "It is the discernment--the knowledge of good and evil--that is at the heart of free will." This idea takes hold in the young heroine. Even after the deaths of her parents and her forced move to the house of her enemy, Octavianus, in Rome, Cleopatra Selene evaluates the choices remaining to her within a course of events seemingly determined by fate.

We also see lighter moments--Cleopatra Selene's proficiency at the game of trigon ("I have beaten the king of Egypt," she says, teasing Caesarion) and her jealousy when her brothers receive Eye of Horus gifts from their mother, not realizing the significance of her own gift (a golden scarab pendant with an emerald in the center). These endow the weightier moments with greater significance. In one standout scene, the children's tutor, Euphronius, takes them to visit the Jewish Quarter in Alexandria. As their teacher explains, the queen "does not force them to act against their faith, thus earning their devotion and allegiance." They meet Rabbi Yoseph ben Zakkai, who encourages their questions, and Cleopatra Selene discovers the concept of "free will." The rabbi explains, "It is the discernment--the knowledge of good and evil--that is at the heart of free will." This idea takes hold in the young heroine. Even after the deaths of her parents and her forced move to the house of her enemy, Octavianus, in Rome, Cleopatra Selene evaluates the choices remaining to her within a course of events seemingly determined by fate. Shecter smoothly balances historical intrigue with classic adolescent romance and abundant details of life in Egypt and Rome--the food, smells, sounds and sights. Key scenes early on establish Cleopatra Selene's sense of confidence and curiosity, as well as the high respect accorded to women in Egypt versus their second-class status in Rome. The author throws some curve balls in the plot's development but, as rereadings will divulge, she plants subtle indicators all along the way. Scrupulous and generous endnotes reveal where Shecter either diverged from the facts or took liberties to fill in missing information.

Shecter smoothly balances historical intrigue with classic adolescent romance and abundant details of life in Egypt and Rome--the food, smells, sounds and sights. Key scenes early on establish Cleopatra Selene's sense of confidence and curiosity, as well as the high respect accorded to women in Egypt versus their second-class status in Rome. The author throws some curve balls in the plot's development but, as rereadings will divulge, she plants subtle indicators all along the way. Scrupulous and generous endnotes reveal where Shecter either diverged from the facts or took liberties to fill in missing information.

How did you first become interested in the lineage of Alexander the Great right through Cleopatra Selene?

How did you first become interested in the lineage of Alexander the Great right through Cleopatra Selene? "Culture is not just something that goes around the world but also goes backward and forward in time," editor Cheryl Klein said. As someone who has edited a number of award-winning translated works, she should know. "A lot of the ideas we discuss now have been wrestled with throughout the ages, like the nature of free will or a ruler's approach." She noted that fiction allows you to see those dramas playing out as they were lived, not just through the history books.

"Culture is not just something that goes around the world but also goes backward and forward in time," editor Cheryl Klein said. As someone who has edited a number of award-winning translated works, she should know. "A lot of the ideas we discuss now have been wrestled with throughout the ages, like the nature of free will or a ruler's approach." She noted that fiction allows you to see those dramas playing out as they were lived, not just through the history books. On your nightstand now:

On your nightstand now: