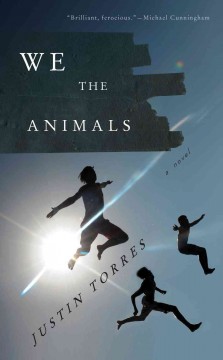

This debut novel's titular "animals" are three boys, nine, eight and six, fighting each other, their parents and life in general. Their Paps is Puerto Rican, big and strong and violent; Mami is white, barely five feet tall, fragile and fierce. There are some good times but mostly bad times in this Brooklyn household. Paps is a serial womanizer, and Mami works the graveyard shift at the brewery. The boys are left, unsupervised, without food, waiting for Mami to come home, wondering if she will be drunk or sober. When Paps disappears for weeks, Mami is too desolate to work, so their situation becomes even worse.

This debut novel's titular "animals" are three boys, nine, eight and six, fighting each other, their parents and life in general. Their Paps is Puerto Rican, big and strong and violent; Mami is white, barely five feet tall, fragile and fierce. There are some good times but mostly bad times in this Brooklyn household. Paps is a serial womanizer, and Mami works the graveyard shift at the brewery. The boys are left, unsupervised, without food, waiting for Mami to come home, wondering if she will be drunk or sober. When Paps disappears for weeks, Mami is too desolate to work, so their situation becomes even worse.

Mami was 14 when Paps, 16, convinced her that what they were up to would not make her pregnant. Despite Paps's reassurances, Manny was born, followed by Joel a year later and then the narrator, Justin, the odd boy out. The disillusionment, desperation, fear and anger felt by these parents--really just kids themselves--is frequently mitigated by their love for each other and for their boys. When Torres writes of the occasional calming influence of their love, it is as if a cooling rain has suddenly fallen on a raging fire. The heartbreaking "You Better Come" has the boys playing a game where they hide in the bathtub behind the shower curtain. The game had been played many times, always ending with the parents "discovering" the boys, to great joy all around. This time, Mami and Paps didn't play properly. The boys vent their terror and anger, their constant feelings of abandonment, by striking their parents, the way they've been hurt. Paps and Mami allow it to go on. They understand their failures; they have been rendered powerless by circumstance.

The three brothers are wild animals, out-of-control marauders in hand-me-down camo clothes, playing war in the woods--who then use all their pocket money to buy milk for a stray cat. They stick together because there is no respite from the privation that is their lives, except curled around each other, feral and afraid.

Justin Torres's first-rate prose will leave you gut-socked and breathless, with a lump in your throat. His style is in-your-face: narrator Justin tries so hard to be macho for his Paps and his Mami, his brothers--and mostly--himself. But macho is not who he is. He is smart, perceptive, Mami's favorite, destined for a better life. He is the glue that holds the wild bunch together. In the end, his true nature is discovered. In "The Night I Was Made," he returns home from cruising the bus station lavatory, to find his family gathered, his mother reading his journal. In a mad scene to rival Lucia di Lammermoor or Ophelia, this "made" boy comes apart altogether. He is filthy, unkempt, reeking of sex and the street, wounded in too many ways and now raging at his family. His father bathes him tenderly; they pack his suitcase and take him to a hospital where his wounds, internal and external, will be cared for. Everyone is exhausted, including the reader, but the redeeming factor here is that the writing is exquisite, making the painful trip so worthwhile. --Valerie Ryan

Shelf Talker: A touching, frightening story of three boys who grow up amid neglect, poverty, violence and occasional moments of pure, radiant love.

and scheduled central libraries as if this discharges them of their obligations. It doesn't. For a child a library needs to be round the corner. And if we lose local libraries it is children who will suffer. Of the libraries I have mentioned the most important for me was that first one, the dark and unprepossessing Armley Junior Library. I had just learned to read. I needed books. Add computers to that requirement maybe but a child from a poor family is today in exactly the same boat."

and scheduled central libraries as if this discharges them of their obligations. It doesn't. For a child a library needs to be round the corner. And if we lose local libraries it is children who will suffer. Of the libraries I have mentioned the most important for me was that first one, the dark and unprepossessing Armley Junior Library. I had just learned to read. I needed books. Add computers to that requirement maybe but a child from a poor family is today in exactly the same boat."

Negotiations continue between Barnes & Noble and Liberty Media, but "constraints on financing

Negotiations continue between Barnes & Noble and Liberty Media, but "constraints on financing  "I am an independent business owner and as such compete with these giant online retailers--Amazon being the biggest gorilla of the group. I collect sales tax and Amazon has not and that gives them an unfair advantage," said Kepler. "It's just time for Amazon to stop being a tax evader and step up and be a real corporate citizen."

"I am an independent business owner and as such compete with these giant online retailers--Amazon being the biggest gorilla of the group. I collect sales tax and Amazon has not and that gives them an unfair advantage," said Kepler. "It's just time for Amazon to stop being a tax evader and step up and be a real corporate citizen." Approximately

Approximately  Author Ann Patchett and publishing veteran Karen Hayes have found a location for their much-anticipated indie bookstore in Nashville, Tenn. They plan to open Parnassus Books this October in Greenbriar Village--where Abbott Martin Rd. meets Hillsboro Pike--with a staff headed by Mary Grey James, formerly of Ingram.

Author Ann Patchett and publishing veteran Karen Hayes have found a location for their much-anticipated indie bookstore in Nashville, Tenn. They plan to open Parnassus Books this October in Greenbriar Village--where Abbott Martin Rd. meets Hillsboro Pike--with a staff headed by Mary Grey James, formerly of Ingram.  In addition to a curated book selection, Parnassus will stock greeting cards and journals, magazines and newspapers, locally produced products and art, and store-branded merchandise. Customers will also be able to buy e-books through the store's website. Web outreach will include an e-mail newsletter,

In addition to a curated book selection, Parnassus will stock greeting cards and journals, magazines and newspapers, locally produced products and art, and store-branded merchandise. Customers will also be able to buy e-books through the store's website. Web outreach will include an e-mail newsletter,  Turn Borders into a "book store" preserved in the style of Colonial Williamsburg ("Ye Olde Borders-Towne"). Replace "old-fashioned" bookshelves with "beautiful, well-appointed downloading pods." These are just two of the suggestions comedian John Hodgman made on Tuesday night's episode of the

Turn Borders into a "book store" preserved in the style of Colonial Williamsburg ("Ye Olde Borders-Towne"). Replace "old-fashioned" bookshelves with "beautiful, well-appointed downloading pods." These are just two of the suggestions comedian John Hodgman made on Tuesday night's episode of the  James Patterson ($84 million)

James Patterson ($84 million) The latest edition of Algonquin Annotations, the publisher's e-newsletter, paid tribute to Carl Lennertz as he prepares for his new role as CEO of the U.S. division of

The latest edition of Algonquin Annotations, the publisher's e-newsletter, paid tribute to Carl Lennertz as he prepares for his new role as CEO of the U.S. division of  CBS Films has released

CBS Films has released  This debut novel's titular "animals" are three boys, nine, eight and six, fighting each other, their parents and life in general. Their Paps is Puerto Rican, big and strong and violent; Mami is white, barely five feet tall, fragile and fierce. There are some good times but mostly bad times in this Brooklyn household. Paps is a serial womanizer, and Mami works the graveyard shift at the brewery. The boys are left, unsupervised, without food, waiting for Mami to come home, wondering if she will be drunk or sober. When Paps disappears for weeks, Mami is too desolate to work, so their situation becomes even worse.

This debut novel's titular "animals" are three boys, nine, eight and six, fighting each other, their parents and life in general. Their Paps is Puerto Rican, big and strong and violent; Mami is white, barely five feet tall, fragile and fierce. There are some good times but mostly bad times in this Brooklyn household. Paps is a serial womanizer, and Mami works the graveyard shift at the brewery. The boys are left, unsupervised, without food, waiting for Mami to come home, wondering if she will be drunk or sober. When Paps disappears for weeks, Mami is too desolate to work, so their situation becomes even worse.