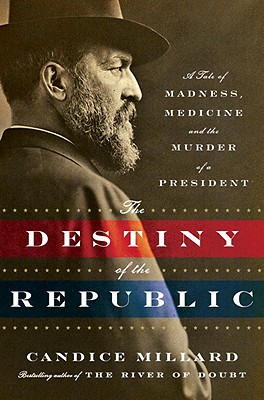

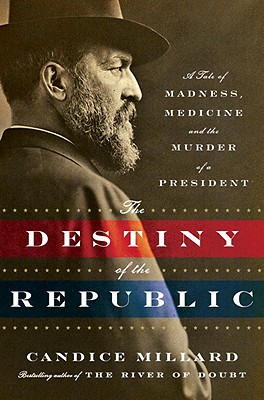

Candice Millard (The River of Doubt: Theodore Roosevelt's Darkest Journey) paints an indelible portrait of the 1876-1882 period, when the United States was still reeling from the Civil War, advances in science and medicine upset long-ingrained superstition, and politics was a blood sport. People believed in forces at work beyond human knowledge. James Garfield, the 20th president, wrote that he could have died of exposure at 16 but God had something greater for him to accomplish. Charles Guiteau, a lawyer and skip-artist, also believed that, having been spared in a steamship collision in June 1880, he had been given a divine mission. These two men, survivors who believed in Providence and divine missions, did have appointments with destiny--but not as they expected and in a way that would shatter the nation.

Candice Millard (The River of Doubt: Theodore Roosevelt's Darkest Journey) paints an indelible portrait of the 1876-1882 period, when the United States was still reeling from the Civil War, advances in science and medicine upset long-ingrained superstition, and politics was a blood sport. People believed in forces at work beyond human knowledge. James Garfield, the 20th president, wrote that he could have died of exposure at 16 but God had something greater for him to accomplish. Charles Guiteau, a lawyer and skip-artist, also believed that, having been spared in a steamship collision in June 1880, he had been given a divine mission. These two men, survivors who believed in Providence and divine missions, did have appointments with destiny--but not as they expected and in a way that would shatter the nation.

Nowhere was the age's tendency to allow accident to prevail over action with intention clearer than in the election of James Garfield in 1880. Garfield did not want the Republican Party's nomination, and he refused to campaign; while others who wanted the office chewed each other up in desperate battles at the nominating convention, he went on to win the election. Millard writes, "Garfield could not shake the feeling that the presidency would bring him only loneliness and sorrow," and he was so right.

Despite the assassination of Lincoln 16 years earlier, the presidency still operated within old traditions. Anybody could walk into the White House; the president traveled without a single security guard; legitimate petitioners and pesky eccentrics had equal access to the president to make requests for government appointments. The clearly unqualified Charles Guiteau, for example, campaigned for ambassadorships to Paris and Vienna during frequent visits to the White House. Denying this particular madman his wishes had serious consequences. In Washington, Guiteau purchased a gun, his first ever, and on July 2, 1881, in the Baltimore and Potomac train station, he fired two shots into the president at close range.

Millard's vivid telling excels on two important points: establishing Guiteau's insanity and describing the medical treatment Garfield received for what should have been a nonlethal wound. "Had Garfield been shot just fifteen years later, the bullet in his back would have been quickly found by X-ray images, and the wound treated with antiseptic surgery," she writes. At the trial during which he used an insanity defense, Guiteau argued that "General Garfield died from malpractice." Guiteau may have been insane, but he was right about that, as the damning autopsy results showed. --John McFarland

Shelf Talker: A brilliantly written account of the tragic time when James Garfield, Civil War hero, pioneering congressman and 20th president, was mowed down by a madman as his administration began.

July bookstore sales fell 4.2% to $982 million compared to July 2010, according to preliminary estimates from the Census Bureau. For the year to date, bookstore sales have dropped 0.5% to $8.03 billion.

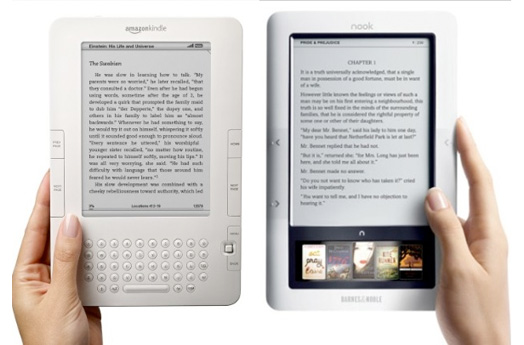

July bookstore sales fell 4.2% to $982 million compared to July 2010, according to preliminary estimates from the Census Bureau. For the year to date, bookstore sales have dropped 0.5% to $8.03 billion. A total of 5.4 million units were shipped during the period, IDC estimated, adding that it expects 27 million e-reader units to be shipped in 2011, up from a previous projection of 16.2 million units.

A total of 5.4 million units were shipped during the period, IDC estimated, adding that it expects 27 million e-reader units to be shipped in 2011, up from a previous projection of 16.2 million units. In the Detroit News,

In the Detroit News,  Edwards said that when he joined Borders in 2009, "it was really presented to me as a classic turnaround." The company, he added, expected to be acquired, and Edwards himself wanted some kind of merger with Barnes & Noble, which consistently showed no interest in a hookup with Borders.

Edwards said that when he joined Borders in 2009, "it was really presented to me as a classic turnaround." The company, he added, expected to be acquired, and Edwards himself wanted some kind of merger with Barnes & Noble, which consistently showed no interest in a hookup with Borders. Aurora Anaya-Cerda, who founded

Aurora Anaya-Cerda, who founded  Congratulations to the Community Bookstore in the Park Slope neighborhood of Brooklyn, N.Y., which is marking its 40th anniversary Saturday as one of the hosts of a Brooklyn Book Festival bookend event. The reading at a nearby church will feature Jonathan Safron Foer, Paul Auster, Siri Hustvedt, Mary Morris and Joe Scieszska.

Congratulations to the Community Bookstore in the Park Slope neighborhood of Brooklyn, N.Y., which is marking its 40th anniversary Saturday as one of the hosts of a Brooklyn Book Festival bookend event. The reading at a nearby church will feature Jonathan Safron Foer, Paul Auster, Siri Hustvedt, Mary Morris and Joe Scieszska.  The 40th annual

The 40th annual  French author

French author  Nigerian author

Nigerian author  Candice Millard (The River of Doubt: Theodore Roosevelt's Darkest Journey) paints an indelible portrait of the 1876-1882 period, when the United States was still reeling from the Civil War, advances in science and medicine upset long-ingrained superstition, and politics was a blood sport. People believed in forces at work beyond human knowledge. James Garfield, the 20th president, wrote that he could have died of exposure at 16 but God had something greater for him to accomplish. Charles Guiteau, a lawyer and skip-artist, also believed that, having been spared in a steamship collision in June 1880, he had been given a divine mission. These two men, survivors who believed in Providence and divine missions, did have appointments with destiny--but not as they expected and in a way that would shatter the nation.

Candice Millard (The River of Doubt: Theodore Roosevelt's Darkest Journey) paints an indelible portrait of the 1876-1882 period, when the United States was still reeling from the Civil War, advances in science and medicine upset long-ingrained superstition, and politics was a blood sport. People believed in forces at work beyond human knowledge. James Garfield, the 20th president, wrote that he could have died of exposure at 16 but God had something greater for him to accomplish. Charles Guiteau, a lawyer and skip-artist, also believed that, having been spared in a steamship collision in June 1880, he had been given a divine mission. These two men, survivors who believed in Providence and divine missions, did have appointments with destiny--but not as they expected and in a way that would shatter the nation.