"I write about history," Walter Dean Myers said, kicking off the Children's Reading Series at the 92nd Street Y in New York City last month. When he was named the National Ambassador for Young People's Literature a year ago, Myers made his credo "Reading is not an option," and his life experience bears it out.

Growing up in Harlem in the 1940s and '50s, Myers remembers the church on Morningside Avenue and 122nd Street, where Langston Hughes sold his books on the steps. James Baldwin lived 12 blocks away. Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in 1947. Truman integrated the armed services in 1948, and, in 1954, Brown v. Board of Education proclaimed segregated public schools unconstitutional. Also in 1954, Myers joined the army, after dropping out of New York's highly competitive Stuyvesant High School at age 15, two years before.

Growing up in Harlem in the 1940s and '50s, Myers remembers the church on Morningside Avenue and 122nd Street, where Langston Hughes sold his books on the steps. James Baldwin lived 12 blocks away. Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in 1947. Truman integrated the armed services in 1948, and, in 1954, Brown v. Board of Education proclaimed segregated public schools unconstitutional. Also in 1954, Myers joined the army, after dropping out of New York's highly competitive Stuyvesant High School at age 15, two years before.

"Why did you drop out?" asked a woman in the audience when Myers opened the floor to questions. "My uncle was murdered, and my family fell apart," he answered. His father spiraled into depression, and his mother became alcoholic. Myers speaks nationwide to young people about reading and writing, and volunteers in juvenile detention centers. He believes the inmates he's met are not lacking intelligence; they're lacking information--"information that's passed down through the family." He cites as an example his first son, who experienced his father as a Vietnam-era soldier, and who's now a chaplain in the army. His second son, Christopher, whom Myers was raising after his career as a writer for young people was already established, is a children's book illustrator. Myers's wife (Christopher's mother) is an artist who studied with Jacob Lawrence. "You learn to think sitting around the dinner table, overhearing your parents. The passing of wisdom from generation to generation around the table--that's changing," Myers said. "Ten- and 11-year-olds are raising the younger children."

During a recent trip to Washington, D.C., Myers struck up a conversation with a cab driver. "You look tired," Myers told the driver. "He said, 'I've just come from being a pall bearer at another teen's funeral.' " The exchange reminded the author of a poem he'd written for his 2004 poetry collection, Here in Harlem (Holiday House), called "J. Milton Brooks, 41: Undertaker." He read: "[T]here comes a time when I have to weep/ It's when we lay some teenage boy so deep/ I close my eyes and pray the Lord to save/ Me from watching old men shuffling children to/ the grave."

When Myers was in his 20s, he had a conversation with Langston Hughes. Hughes had been criticized for writing for "the lowest element of black life," as Myers put it. Hughes told Myers, "That's who I want to write for." In his book Just Write: Here's How! (HarperCollins, 2012) Myers says, "Reading probably saved my life." Literally. For him, reading was not an option, it was essential. He also says, in Just Write, "I write books for the troubled boy I once was, and for the boy who lives within me still." He worries about those kids who begin school behind, and how only 15% of them ever catch up.

A teenage boy in the audience asked Myers if his book Monster (the inaugural Printz Award winner) was based on one of the prisoners with whom he's worked. Yes, Myers answered. "There are young people committing crimes for no apparent reason. They're not thinking it through. One kid spent two-and-a-half years in jail for being a lookout man [for a robbery gone wrong that ended in murder]." Steve Harmon in Monster was inspired by that kid.

"Prisoners want to know, if I dropped out of high school, how did I get where I am?" said Myers. "I tell them, 'I dropped out of high school but I didn't drop out of reading books.' "--Jennifer M. Brown

"E-books, in other words, may turn out to be just another format--an even lighter-weight, more disposable paperback. That would fit with the discovery that once people start buying digital books, they don't necessarily stop buying printed ones. In fact, according to Pew, nearly 90% of e-book readers continue to read physical volumes. The two forms seem to serve different purposes.

"E-books, in other words, may turn out to be just another format--an even lighter-weight, more disposable paperback. That would fit with the discovery that once people start buying digital books, they don't necessarily stop buying printed ones. In fact, according to Pew, nearly 90% of e-book readers continue to read physical volumes. The two forms seem to serve different purposes.

Many thanks to the more than 120 booksellers and bloggers who have embedded our book giveaway button their websites and blogs. We're kicking off the new year by

Many thanks to the more than 120 booksellers and bloggers who have embedded our book giveaway button their websites and blogs. We're kicking off the new year by BINC.1203.T2.ANONYMOUSDONORMATCH.jpg)

A day-long workshop for prospective booksellers and new bookstore owners and managers called How to Succeed at Retail Bookselling: Introduction to the Bookstore Business will be held Friday, February 22, the day before the beginning of the ABA's Winter Institute 8 in Kansas City, Mo.

A day-long workshop for prospective booksellers and new bookstore owners and managers called How to Succeed at Retail Bookselling: Introduction to the Bookstore Business will be held Friday, February 22, the day before the beginning of the ABA's Winter Institute 8 in Kansas City, Mo. Written Words Bookstore, Shelton, Conn., must relocate by the end of the month

Written Words Bookstore, Shelton, Conn., must relocate by the end of the month

Cameron Books

Cameron Books

Growing up in Harlem in the 1940s and '50s, Myers remembers the church on Morningside Avenue and 122nd Street, where Langston Hughes sold his books on the steps. James Baldwin lived 12 blocks away. Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in 1947. Truman integrated the armed services in 1948, and, in 1954, Brown v. Board of Education proclaimed segregated public schools unconstitutional. Also in 1954, Myers joined the army, after dropping out of New York's highly competitive Stuyvesant High School at age 15, two years before.

Growing up in Harlem in the 1940s and '50s, Myers remembers the church on Morningside Avenue and 122nd Street, where Langston Hughes sold his books on the steps. James Baldwin lived 12 blocks away. Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in 1947. Truman integrated the armed services in 1948, and, in 1954, Brown v. Board of Education proclaimed segregated public schools unconstitutional. Also in 1954, Myers joined the army, after dropping out of New York's highly competitive Stuyvesant High School at age 15, two years before. A very young girl, yearning to escape her provincial beginnings, is swept up into an ill-advised romance with a much older, more sophisticated, totally inappropriate man who educates her in sex and heartbreak.

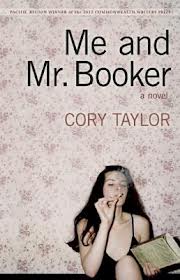

A very young girl, yearning to escape her provincial beginnings, is swept up into an ill-advised romance with a much older, more sophisticated, totally inappropriate man who educates her in sex and heartbreak.