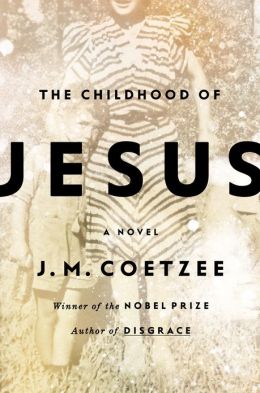

Though no one named Jesus ever appears in J.M. Coetzee's The Childhood of Jesus, there are parallels aplenty to the story of Jesus, Mary and Joseph, reworked into a modern context that reads like science fiction, taking place in an unnamed Spanish-speaking country where the people are decent, well-intentioned, strangely satisfied, don't eat meat, don't fight and don't charge for services.

Though no one named Jesus ever appears in J.M. Coetzee's The Childhood of Jesus, there are parallels aplenty to the story of Jesus, Mary and Joseph, reworked into a modern context that reads like science fiction, taking place in an unnamed Spanish-speaking country where the people are decent, well-intentioned, strangely satisfied, don't eat meat, don't fight and don't charge for services.

Five-year-old David and his 50ish guardian, Simon, have just arrived by boat in the Relocation Center. David is a slim, pale-faced child without parents, often confused and upset, extremely bright but troubled, who writes words only he understands. He loves numbers but doesn't understand numerical sequence. He lives in terror of falling through a crack in the sidewalk. They've come there to find the boy's mother, whose name has been lost at sea. Simon gets hired as a stevedore to unload vessels at the docks.

Too complicated and realistic to be an allegory, too multi-dimensional and idiosyncratic to be a fable, Coetzee's surreal philosophical discourse on childrearing and education still manages to remain human and frequently touching. Coetzee is known for his pessimism--his Booker Prize-winning Disgrace has one of the most depressing endings in modern fiction--but the world Simon finds himself in is surprisingly warm-hearted. The foreman at the docks not only minds David while his guardian works, he even loans them money.

The novel's intentionally artificial conversations sound like Platonic dialogues, questioning and debating abstractions like beauty and erotic desire, goodwill and love, stealing and parenting, seasoned with enjoyable discussions of Don Quixote. Impulsively, Simon decides that a wealthy young woman playing tennis is the boy's mother. He announces as much to her; more astonishing yet, she agrees to adopt the boy. Coetzee's characters, though recognizably human, don't act like any human beings you know. They seem to exist on a different planet where goodwill has replaced passion.

In this small, baffling riddle of a novel, where people arrive mysteriously by boat, washed clean of memory, to labor in a peaceful agrarian world, David grows more and more out of control. Running away from school, defying his teachers, he begins gathering doctors and hitchhikers like apostles and saying things like, "You must call me by my real name" and "Yo soy la verdad." What exactly Coetzee has in mind is anyone's guess, but just try to stop puzzling over this thought-provoking novel after finishing it. --Nick DiMartino

Shelf Talker: In Nobel Prize-winner Coetzee's mysterious new novel, a five-year-old boy and his guardian go in search of the boy's mother in an unnamed Spanish-speaking utopia.

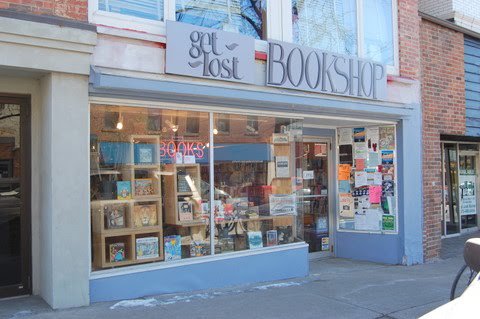

"The good news is that, as consumers, we are free to do exactly that. We decide the fate of bookstores, and of literature itself, with every book we buy. If you value your bookstore and think it plays an important role in your community, then buy your books there.

"The good news is that, as consumers, we are free to do exactly that. We decide the fate of bookstores, and of literature itself, with every book we buy. If you value your bookstore and think it plays an important role in your community, then buy your books there.

SHELFAWARENESS.1222.S1.BESTADSWEBINAR.gif)

SHELFAWARENESS.1222.T1.BESTADSWEBINAR.gif)

A pair of former Kepler's Books staff members are

A pair of former Kepler's Books staff members are  As they explained on the home page for their

As they explained on the home page for their  Cheryl and Steve Hare, who were

Cheryl and Steve Hare, who were  In an unusual twist that emphasizes that he is arguably the most powerful man in publishing, Markus Dohle, CEO of Penguin Random House, will be the sole guest speaker at this year's CEO Debate at the Frankfurt Book Fair. The event usually features a panel of publishing CEOs.

In an unusual twist that emphasizes that he is arguably the most powerful man in publishing, Markus Dohle, CEO of Penguin Random House, will be the sole guest speaker at this year's CEO Debate at the Frankfurt Book Fair. The event usually features a panel of publishing CEOs. Recovery efforts continue in Calgary, Alberta, from

Recovery efforts continue in Calgary, Alberta, from  Recently, the digital publishing company DailyLit was making plans to put out new electronic editions of several public domain works of literature. But Jennifer 8. Lee, co-founder of DailyLit's parent company, Plympton, wanted these e-books to stand out from other versions of the same titles--and, she explained, "I didn't want to use auto-generated covers." So she got in touch with the Creative Action Network, and together they worked out the concept behind

Recently, the digital publishing company DailyLit was making plans to put out new electronic editions of several public domain works of literature. But Jennifer 8. Lee, co-founder of DailyLit's parent company, Plympton, wanted these e-books to stand out from other versions of the same titles--and, she explained, "I didn't want to use auto-generated covers." So she got in touch with the Creative Action Network, and together they worked out the concept behind

On Friday,

On Friday,  Describing it as "a charity we believe in strongly," Brooklyn's

Describing it as "a charity we believe in strongly," Brooklyn's  A Tap on the Window

A Tap on the Window Though no one named Jesus ever appears in J.M. Coetzee's The Childhood of Jesus, there are parallels aplenty to the story of Jesus, Mary and Joseph, reworked into a modern context that reads like science fiction, taking place in an unnamed Spanish-speaking country where the people are decent, well-intentioned, strangely satisfied, don't eat meat, don't fight and don't charge for services.

Though no one named Jesus ever appears in J.M. Coetzee's The Childhood of Jesus, there are parallels aplenty to the story of Jesus, Mary and Joseph, reworked into a modern context that reads like science fiction, taking place in an unnamed Spanish-speaking country where the people are decent, well-intentioned, strangely satisfied, don't eat meat, don't fight and don't charge for services.