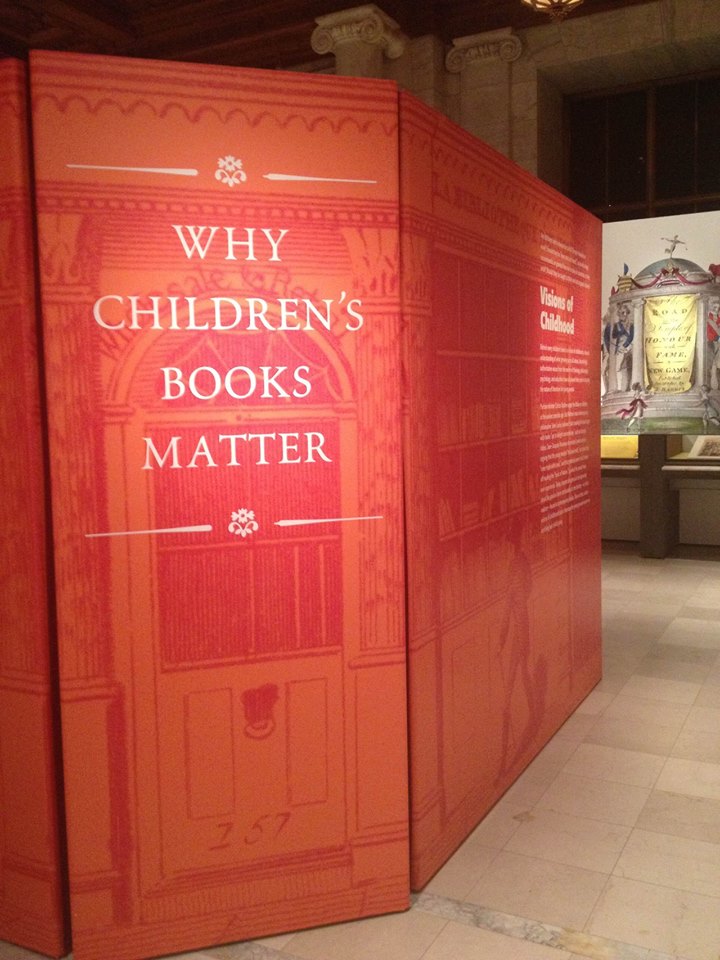

In the exhibition "The ABC of It: Why Children's Books Matter," now on view at the New York Public Library's Fifth Avenue branch, Leonard Marcus locates American children's literature at the center of society--its values, its beliefs about education, and its efforts to instill those values and beliefs in its youth through literature.

In the exhibition "The ABC of It: Why Children's Books Matter," now on view at the New York Public Library's Fifth Avenue branch, Leonard Marcus locates American children's literature at the center of society--its values, its beliefs about education, and its efforts to instill those values and beliefs in its youth through literature.

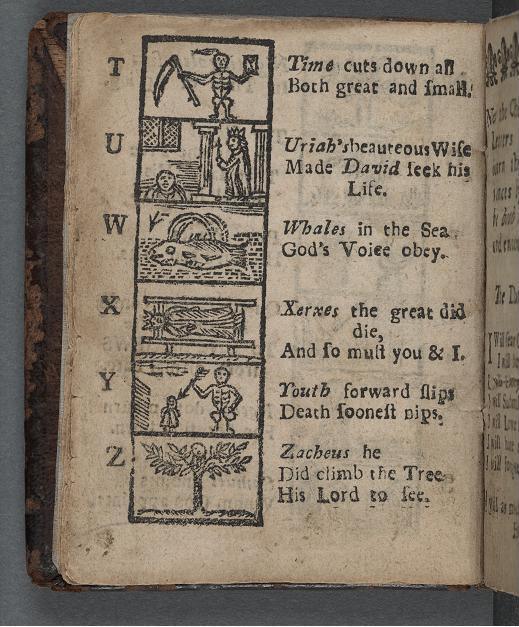

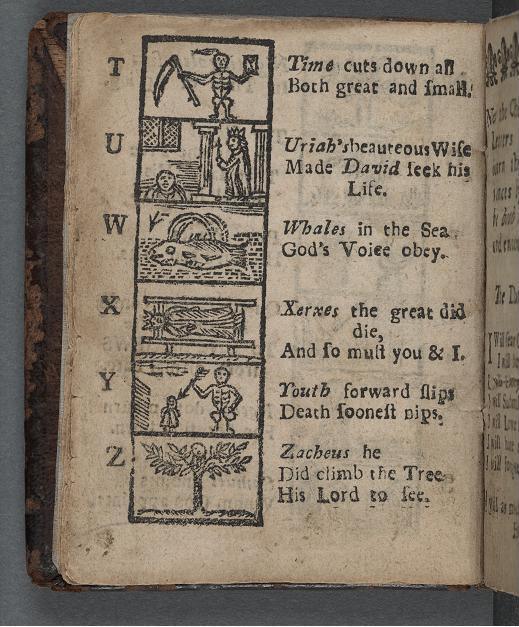

The exhibit opens with what is believed to be one of the oldest New England Primers still in existence, which, Marcus said, is normally kept "in a vault that would be the envy of Fort Knox." Its estimated value is $1 million. "In Adam's Fall/ We Sinned all./ Thy Life to Mend/ This Book Attend./ The Cat doth play/ and after flay." These are the ABCs according to that 1727 primer. Against a backdrop on a wall designed as an open book, the primer takes the right hand–page position. On the left is William Blake's Songs of Innocence, illustrated with Blake's own watercolors.

The exhibit opens with what is believed to be one of the oldest New England Primers still in existence, which, Marcus said, is normally kept "in a vault that would be the envy of Fort Knox." Its estimated value is $1 million. "In Adam's Fall/ We Sinned all./ Thy Life to Mend/ This Book Attend./ The Cat doth play/ and after flay." These are the ABCs according to that 1727 primer. Against a backdrop on a wall designed as an open book, the primer takes the right hand–page position. On the left is William Blake's Songs of Innocence, illustrated with Blake's own watercolors.

Are children born sinful or innocent? This is the lens through which Marcus frames the implicit societal, literary debate that follows. Can children acquire information through inquiry or must they be taught by rote? Nathaniel Hawthorne, the great-great-grandson of the Salem witch trials' presiding judge, "felt forever haunted by his Puritan past," Marcus said, adding that fiction writing for Hawthorne was "an act of personal rebellion against his dour, unforgiving ancestors." Before the publication of The Scarlet Letter, Hawthorne wrote children's books under a pen name. If Hawthorne is an example of the transition from Puritanical to more imaginative texts, the progressive education movement--with John Dewey, Maria Montessori and Lucy Sprague Mitchell at the forefront--represented a clean break.

Marcus dedicates a full subsection to the Bank Street School (originally the Bureau of Educational Experiments, located in New York's Greenwich Village and founded by Mitchell), with Harold and his purple crayon leading viewers into the Great Green Room of Goodnight Moon. Children may climb up into a window seat next to a picture of the cow jumping over the moon, memorialized in Clement Hurd's illustrations of Margaret Wise Brown's text. Mitchell and the Bank Street Writers Lab members--Crockett Johnson, Margaret Wise Brown, Maurice Sendak, Ruth Krauss and Edward Steichen, among others--wrote about children exploring their world, and recorded the sights and sounds of their immediate environment, often incorporating overheard phrases from children.

Marcus dedicates a full subsection to the Bank Street School (originally the Bureau of Educational Experiments, located in New York's Greenwich Village and founded by Mitchell), with Harold and his purple crayon leading viewers into the Great Green Room of Goodnight Moon. Children may climb up into a window seat next to a picture of the cow jumping over the moon, memorialized in Clement Hurd's illustrations of Margaret Wise Brown's text. Mitchell and the Bank Street Writers Lab members--Crockett Johnson, Margaret Wise Brown, Maurice Sendak, Ruth Krauss and Edward Steichen, among others--wrote about children exploring their world, and recorded the sights and sounds of their immediate environment, often incorporating overheard phrases from children.

The exhibit offers a number of other opportunities for children to experience the exhibit: they may climb into a car that's part of The Phantom Tollbooth display, disappear down the rabbit hole into an Alice in Wonderland exhibit (don't miss the parasol handle of Tweedledum and Tweedledee, plus Lewis Carroll's letter to the real Alice who served as his muse), and walk through a fur-covered silhouette of Max in his Wild Things outfit.

The exhibit offers a number of other opportunities for children to experience the exhibit: they may climb into a car that's part of The Phantom Tollbooth display, disappear down the rabbit hole into an Alice in Wonderland exhibit (don't miss the parasol handle of Tweedledum and Tweedledee, plus Lewis Carroll's letter to the real Alice who served as his muse), and walk through a fur-covered silhouette of Max in his Wild Things outfit.

Marcus also showcases children's books from around the world, and brings to the fore some entries that may well surprise viewers--e.g., a bilingual book published in Lakota and English, Lak'ota pte'ole hoksila lowansa by Ann Clark (Singing Sioux Cowboy Reader, 1947).

Nowhere is the impact of societal debate more keenly felt than in a section on comic books, "Lights Out: Reading Under the Covers," where children may slip into a cubby designed to evoke a clandestine rendezvous with a book under blankets, with flashlight. In an exhibit case above the cubby is a major reason the fruit was forbidden: Seduction of the Innocent by Frederic Wertham (Rinehart & Co, 1954), which asserted comics' society-eroding effects. Just around the corner from the comics, viewers discover a wall of banned books, spine out. Each spine features a title in dispute or removed at one time from school and library shelves. Marcus calls out a few famous examples, such as Madeleine L'Engle's A Wrinkle in Time--pulled both for being, at different times, too religious and sacrilegious.

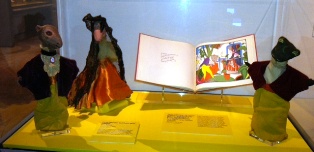

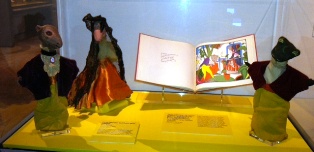

Marcus brings into focus the key role that the New York Public Library and its librarians played in bringing together the larger community, with photos of African American librarian Augusta Baker in Harlem, and a display case with the puppets and picture books (such as Pérez y Martina) of Pura Belpré, the NYPL's first Latina librarian. Items in the exhibit come from all over the New York Public Library's archives, including the Rare Book Division, the Henry W. and Albert A. Berg collection of English and American Literature, the Carl H. Pforzheimer Collection of Shelley and His Circle and the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

Marcus brings into focus the key role that the New York Public Library and its librarians played in bringing together the larger community, with photos of African American librarian Augusta Baker in Harlem, and a display case with the puppets and picture books (such as Pérez y Martina) of Pura Belpré, the NYPL's first Latina librarian. Items in the exhibit come from all over the New York Public Library's archives, including the Rare Book Division, the Henry W. and Albert A. Berg collection of English and American Literature, the Carl H. Pforzheimer Collection of Shelley and His Circle and the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

The captions, which do not exceed 100 words, convey both Marcus's wit and scholarship. For the 1727 edition of the New England Primer, for instance, Marcus cites the entry, "Our King the good/ No Man of Blood," and writes that by 1791, "a new sentiment was clearly in order.... 'The British King/ Lost States thirteen.' " Ever mindful of families attending with children--in addition to the interactive elements--Marcus includes the milestone event of Harry Potter's entrance on the scene, with global sales of "forest-rattling proportions" and precipitating the New York Times' juvenile bestseller list, "aimed at keeping the world safe for the usual potboilers and thrillers," writes Marcus.

The exhibit redeems comics in a section called "Comics Grow Up" and includes works by Will Eisner, Art Spiegelman, Shaun Tan's The Arrival and Brian Selznick's Caldecott Medal–winning The Invention of Hugo Cabret. Near the close of the exhibit, a wall of Ashley Bryan's paintings from Let It Shine lets viewers know that Bryan's awakening as an artist began in part due to his work on the WPA projects. At one time, society valued art enough to fund projects like these. Marcus subtly brings the exhibit full circle, and a question lingers: Where are the WPA projects of today? How do we encourage aspiring artists and writers, especially those of diverse cultures and perspectives, to become involved in the arts when so much of it is disappearing from schools, along with its funding? There is much food for thought in this inclusive history of children's literature, on display through March 23, 2014. --Jennifer M. Brown

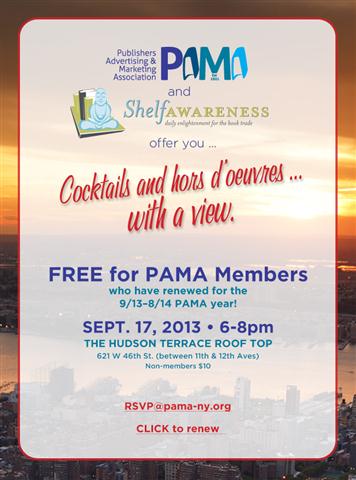

The Publishers Advertising and Marketing Association and Shelf Awareness invite you to join us next Tuesday evening for "cocktails and hors d'oeuvres--with a view." The party takes place September 17, 6-8 p.m., at the Hudson Terrace Rooftop, at 621 W. 46th St. (between 11th and 12th Avenues) in Manhattan. It's free for PAMA members; $10 for nonmembers. RSVP to RSVP@pama-ny.org. Hope to see you there!

The Publishers Advertising and Marketing Association and Shelf Awareness invite you to join us next Tuesday evening for "cocktails and hors d'oeuvres--with a view." The party takes place September 17, 6-8 p.m., at the Hudson Terrace Rooftop, at 621 W. 46th St. (between 11th and 12th Avenues) in Manhattan. It's free for PAMA members; $10 for nonmembers. RSVP to RSVP@pama-ny.org. Hope to see you there!

SHELFAWARENESS.1222.S1.BESTADSWEBINAR.gif)

SHELFAWARENESS.1222.T1.BESTADSWEBINAR.gif)

"Part of the consultation process was that anybody could take voluntary redundancy and in the end quite a few did, which included some people we might not have wanted to go," Waterstones managing director James Daunt said. "I think that part has been a relatively positive side of this--there were people who wanted to stay but there were also people who wanted to go, and those people have a chance to go in a different direction."

"Part of the consultation process was that anybody could take voluntary redundancy and in the end quite a few did, which included some people we might not have wanted to go," Waterstones managing director James Daunt said. "I think that part has been a relatively positive side of this--there were people who wanted to stay but there were also people who wanted to go, and those people have a chance to go in a different direction." E-reading devices are touted for their convenience when on the road, but a recent survey by London's Heathrow Airport found that

E-reading devices are touted for their convenience when on the road, but a recent survey by London's Heathrow Airport found that  Last night Oliver Pötzsch launched the U.S. tour for his new novel, The Ludwig Conspiracy (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt), with a reading at Die Stammkneipe beer garden, just down the street from Brooklyn's

Last night Oliver Pötzsch launched the U.S. tour for his new novel, The Ludwig Conspiracy (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt), with a reading at Die Stammkneipe beer garden, just down the street from Brooklyn's  Congratulations to

Congratulations to  To buy or to borrow... that is the question. Messy Nessy highlighted "

To buy or to borrow... that is the question. Messy Nessy highlighted "

As Flies to Whatless Boys: A Novel

As Flies to Whatless Boys: A Novel When Tony Hillerman died in 2008, it was a sad day for fans of Lt. Joe Leaphorn and Sergeant Jim Chee of the Navajo Tribal Police. But wait! Thankfully, his daughter Anne has taken up the torch with Spider Woman's Daughter, offering her take on these memorable and beloved characters.

When Tony Hillerman died in 2008, it was a sad day for fans of Lt. Joe Leaphorn and Sergeant Jim Chee of the Navajo Tribal Police. But wait! Thankfully, his daughter Anne has taken up the torch with Spider Woman's Daughter, offering her take on these memorable and beloved characters.

In the exhibition "

In the exhibition " The exhibit opens with what is believed to be one of the oldest New England Primers still in existence, which, Marcus said, is normally kept "in a vault that would be the envy of Fort Knox." Its estimated value is $1 million. "In Adam's Fall/ We Sinned all./ Thy Life to Mend/ This Book Attend./ The Cat doth play/ and after flay." These are the ABCs according to that 1727 primer. Against a backdrop on a wall designed as an open book, the primer takes the right hand–page position. On the left is William Blake's Songs of Innocence, illustrated with Blake's own watercolors.

The exhibit opens with what is believed to be one of the oldest New England Primers still in existence, which, Marcus said, is normally kept "in a vault that would be the envy of Fort Knox." Its estimated value is $1 million. "In Adam's Fall/ We Sinned all./ Thy Life to Mend/ This Book Attend./ The Cat doth play/ and after flay." These are the ABCs according to that 1727 primer. Against a backdrop on a wall designed as an open book, the primer takes the right hand–page position. On the left is William Blake's Songs of Innocence, illustrated with Blake's own watercolors. Marcus dedicates a full subsection to the Bank Street School (originally the Bureau of Educational Experiments, located in New York's Greenwich Village and founded by Mitchell), with Harold and his purple crayon leading viewers into the Great Green Room of Goodnight Moon. Children may climb up into a window seat next to a picture of the cow jumping over the moon, memorialized in Clement Hurd's illustrations of Margaret Wise Brown's text. Mitchell and the Bank Street Writers Lab members--Crockett Johnson, Margaret Wise Brown, Maurice Sendak, Ruth Krauss and Edward Steichen, among others--wrote about children exploring their world, and recorded the sights and sounds of their immediate environment, often incorporating overheard phrases from children.

Marcus dedicates a full subsection to the Bank Street School (originally the Bureau of Educational Experiments, located in New York's Greenwich Village and founded by Mitchell), with Harold and his purple crayon leading viewers into the Great Green Room of Goodnight Moon. Children may climb up into a window seat next to a picture of the cow jumping over the moon, memorialized in Clement Hurd's illustrations of Margaret Wise Brown's text. Mitchell and the Bank Street Writers Lab members--Crockett Johnson, Margaret Wise Brown, Maurice Sendak, Ruth Krauss and Edward Steichen, among others--wrote about children exploring their world, and recorded the sights and sounds of their immediate environment, often incorporating overheard phrases from children. The exhibit offers a number of other opportunities for children to experience the exhibit: they may climb into a car that's part of The Phantom Tollbooth display, disappear down the rabbit hole into an Alice in Wonderland exhibit (don't miss the parasol handle of Tweedledum and Tweedledee, plus Lewis Carroll's letter to the real Alice who served as his muse), and walk through a fur-covered silhouette of Max in his Wild Things outfit.

The exhibit offers a number of other opportunities for children to experience the exhibit: they may climb into a car that's part of The Phantom Tollbooth display, disappear down the rabbit hole into an Alice in Wonderland exhibit (don't miss the parasol handle of Tweedledum and Tweedledee, plus Lewis Carroll's letter to the real Alice who served as his muse), and walk through a fur-covered silhouette of Max in his Wild Things outfit. Marcus brings into focus the key role that the New York Public Library and its librarians played in bringing together the larger community, with photos of African American librarian Augusta Baker in Harlem, and a display case with the puppets and picture books (such as Pérez y Martina) of Pura Belpré, the NYPL's first Latina librarian. Items in the exhibit come from all over the New York Public Library's archives, including the Rare Book Division, the Henry W. and Albert A. Berg collection of English and American Literature, the Carl H. Pforzheimer Collection of Shelley and His Circle and the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

Marcus brings into focus the key role that the New York Public Library and its librarians played in bringing together the larger community, with photos of African American librarian Augusta Baker in Harlem, and a display case with the puppets and picture books (such as Pérez y Martina) of Pura Belpré, the NYPL's first Latina librarian. Items in the exhibit come from all over the New York Public Library's archives, including the Rare Book Division, the Henry W. and Albert A. Berg collection of English and American Literature, the Carl H. Pforzheimer Collection of Shelley and His Circle and the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.