|

|

Jon Scieszka, Kate DiCamillo, Walter Dean Myers

|

Friday morning, at the Thomas Jefferson Building of the Library of Congress, author Kate DiCamillo was sworn in as the National Ambassador for Young People's Literature. She is the fourth author to hold this position; Jon Scieszka was the first, followed by Katherine Paterson, and most recently, Walter Dean Myers.

Congresswoman Debbie Wasserman Schultz (D.-Fla.), who played a key role in establishing the Young Readers Center in the Jefferson Building, hailed the author, who grew up in Florida, as an example that "the Gator Nation is everywhere." Congressman Robert Aderholt (R.-Ala.), who serves with Wasserman Schultz on the House Committee on Appropriations, also congratulated DiCamillo. "The books we read as children become the narratives of our lives," he said.

|

|

John Cole, director of the Center for the Book at the Library of Congress, welcoming new National Ambassador for Young People's Literature Kate DiCamillo.

|

John Cole, director of the Library of Congress's Center for the Book, served as master of ceremonies. "We're a young program, but we do have traditions," he said. One is that the outgoing National Ambassador for Young People's Literature pass the baton to the incoming Ambassador. He invited Walter Dean Myers to the podium. "I was prepared for the frequent travel," Myers said. He travels so often that the cashier at the airport newsstand sees him and says, "Peanuts again?" Myers continued, "I was prepared for people saying, 'You're my favorite author.' What I was not prepared for was to find so many people eager to hear what I had to say. They understand that reading is important." Myers described what he called the most important moment in his two years as ambassador: "I was in a prison that was loosely run. By that I mean, some talking is allowed among the inmates," Myers said. When he started to speak, an inmate was talking. "'Keep quiet, I want to hear this,' one inmate said to the other," Myers recalled. "That touched me. I knew this program was working."

Kate DiCamillo told a tale from her life as an example of how "Stories Connect Us," her platform as ambassador. It's the story of a silver fish and a blue dolphin, set in Silver Springs, Fla., where monkeys swing through the treetops and glass-bottom boats take passengers down the Silver River.

At age eight, DiCamillo took a ride in a glass-bottom boat. A silver fish swam beneath her. A woman, a total stranger, grabbed her wrist. " 'Did you see that?' the stranger asked," DiCamillo recalled. "Her face was open. She wore a rain bonnet even though the sun was shining." Terribly shy, DiCamillo said, "There goes a turtle." "That's right," the stranger replied, "That's a turtle. Oh my, this world."

The eight-year-old Kate saw it all as if viewing it from above. She felt a part of everything. Her mother asked her who the woman was. "She was just someone I was looking at things with," DiCamillo told her gregarious mother, who had no concept of how she could have such a shy daughter. "I had opened a bit," DiCamillo realized. "I was a tiny bit awake."

In 1972, Kate DiCamillo had Mrs. Boyette as a second-grade teacher. She was old and short-tempered. "I loved her with the whole of myself," said DiCamillo. "She read aloud to us Island of the Blue Dolphins by Scott O'Dell." In her class was a boy named Tony Fenchel, who "liked to trip me," she said. "I've changed his name." Not only was she a "preternaturally shy child," DiCamillo admitted, "I was a terrified child." When Mrs. Boyette read the scene in which Karana tames a wild dog, young Kate was on the edge of her seat. "I looked over at Tony Fenchel. Tony Fenchel was on the edge of his seat, too. I smiled at him. He smiled at me. Tony Fenchel was like me; he was not a monster."

|

|

On the eve of DiCamillo's inauguration, the ambassadors gathered at at Politics & Prose: (l.-r.) Jon Scieszka, Kate DiCamillo, Katherine Paterson.

|

DiCamillo likened Island of the Blue Dolphins to the glass-bottom boat: "That book had the feeling of a world hidden under the world I already knew." She floated above her second-grade classroom, much as she did in that glass-bottom boat. "Oh my, this world," said DiCamillo.

"Did Tony Fenchel stop tripping me?" DiCamillo continued. "He did not. But I could not go back to seeing him as a monster. Stories for me are a glass-bottom boat ride. We see each other; we open up. We change. Everyone is together in a room. Everyone is connected." When we read together, grandparent to grandchild, parent to child, teacher to student, brother to sister, said DiCamillo, "We are taken off that horrible rock of our aloneness. I want to work to bring more people together into a room." --Jennifer M. Brown

SHELFAWARENESS.0213.S4.DIFFICULTTOPICSWEBINAR.gif)

Borland is seeking help because she learned during the holiday season that she will begin providing the sole support for her 25-year-old son, who has autism. "A bookshop requires a 100% commitment of time, energy, and devotion, and I suddenly find myself unable to provide that," she said.

Borland is seeking help because she learned during the holiday season that she will begin providing the sole support for her 25-year-old son, who has autism. "A bookshop requires a 100% commitment of time, energy, and devotion, and I suddenly find myself unable to provide that," she said.

SHELFAWARENESS.0213.T3.DIFFICULTTOPICSWEBINAR.gif)

More about

More about

Among examples:

Among examples:  Sheila Daley, owner of the

Sheila Daley, owner of the  Romance Is My Day Job: A Memoir of Finding Love at Last

Romance Is My Day Job: A Memoir of Finding Love at Last While book-to-screen adaptations did not dominate last night's

While book-to-screen adaptations did not dominate last night's

The National Book Critics Circle has chosen the

The National Book Critics Circle has chosen the  Random House is moving up the on-sale date of The Loudest Voice in the Room: How the Brilliant, Bombastic Roger Ailes Built Fox News--and Divided a Country by Gabriel Sherman to tomorrow from January 21 because of what the publisher calls "heavy media attention."

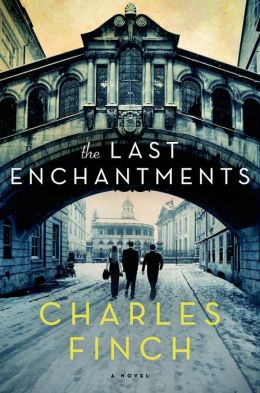

Random House is moving up the on-sale date of The Loudest Voice in the Room: How the Brilliant, Bombastic Roger Ailes Built Fox News--and Divided a Country by Gabriel Sherman to tomorrow from January 21 because of what the publisher calls "heavy media attention." In The Last Enchantments, an engagingly written novel about a young American man coming of age at Oxford, Charles Finch departs from his usual historical mysteries (A Beautiful Blue Death, etc.). Instead, he sets the scene in a place where the past and present are in a constant state of fusion. Twenty-five-year-old Will Baker has, to all appearances, an enviable life: a career in politics he enjoys, a wealthy and sympathetic girlfriend and a glamorous lifestyle in New York City, where going out to clubs at midnight is seen as getting an early start. Despite having what most Americans would equate to success, however, Will is restless and desirous of a change.

In The Last Enchantments, an engagingly written novel about a young American man coming of age at Oxford, Charles Finch departs from his usual historical mysteries (A Beautiful Blue Death, etc.). Instead, he sets the scene in a place where the past and present are in a constant state of fusion. Twenty-five-year-old Will Baker has, to all appearances, an enviable life: a career in politics he enjoys, a wealthy and sympathetic girlfriend and a glamorous lifestyle in New York City, where going out to clubs at midnight is seen as getting an early start. Despite having what most Americans would equate to success, however, Will is restless and desirous of a change.