Thursday night in Manhattan, at Florence Gould Hall at the French Institute Alliance Française (FIAF), Leonard Lopate led a discussion with cartoonists Art Spiegelman, Molly Crabapple, Emmanuel "Manu" Letouzé and New Yorker cover director Françoise Mouly about the Charlie Hebdo murders and what's next. The FIAF, PEN American Center and the National Coalition Against Censorship sponsored the program.

|

|

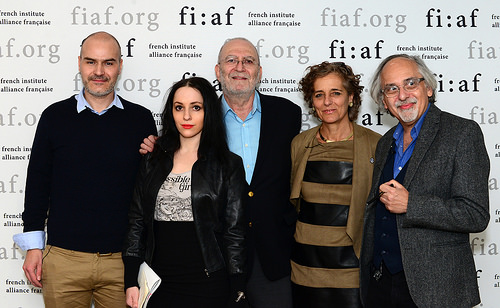

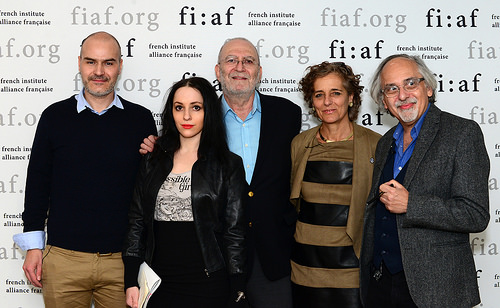

"After Charlie" speakers: (l.-r.) Emmanuel "Manu" Letouze, Molly Crabapple, moderator Leonard Lopate, Françoise Mouly and Art Spiegelman.]

|

Leonard Lopate posited that William Hogarth, working in the 18th century, was the first political cartoonist, but suggested that Charlie Hebdo was the first to be punished for its satire. Cartoonist and journalist Molly Crabapple pointed out the power of visual satire: "Op-ed pieces are tied to a certain language," she said, "but art you can yank out of context." Lopate quoted Boss Tweed, who infamously said, "Stop the pictures! My constituents can't read, but they can see pictures!"

New Yorker art director, French-born Françoise Mouly, described the difference between French and American points of view, when it came to Charlie Hebdo. "In France, the written press joined with the artists," she said, while in the U.S., "there's a fear of artists not being totally toilet-trained." Her husband, Art Spiegelman, Pulitzer Prize–winning creator of Maus, added, "Jon Stewart and Stephen Colbert are the closest we have to political cartoonists."

Socio-political cartoonist Emmanuel "Manu" Letouzé said he was 21 when he first met Charlie's editor-in-chief, Philippe Val. "Working for Charlie was my dream," Manu wrote in a strip called "They killed my idols." He said, "These were not racists. Context is the point." Mouly added, "Charlie Hebdo's roots were in the 1960s, when it was far more important to fight the established order. When Charlie got the interdiction [at that time], they became a rallying point. They went from 10,000 to 100,000 circulation--thanks to the censorship. They provoked the discussion of how far you can go, and what's too far."

Crabapple expanded on the idea of a line to be crossed: "There's the law that bans it, but then you're outsourcing your ethics to the State." She described her experience visiting Guantanamo as "the most censored place." She had to wear identification as "escort of the military" and was not allowed to draw the faces of anyone who works there. She received death threats after her Gitmo piece was published. "The only faces are the prisoners,' " Crabapple said.

Crabapple expanded on the idea of a line to be crossed: "There's the law that bans it, but then you're outsourcing your ethics to the State." She described her experience visiting Guantanamo as "the most censored place." She had to wear identification as "escort of the military" and was not allowed to draw the faces of anyone who works there. She received death threats after her Gitmo piece was published. "The only faces are the prisoners,' " Crabapple said.

Spiegelman described another line crossed, when he began doing covers for the New Yorker. "My model was MAD," Spiegelman said. "The New Yorker at that time was 'it's nice in Connecticut' kind of covers." In describing his approach to the February 15, 1993, cover, a reference to the Crown Heights riots, he said, "I doodled the New Yorker fellow and thought, 'What would he look like if he were Jewish?" The cover depicts a Hasidic Jew and an African American woman kissing. Lopate asked, "Who was upset by it?" Everyone, essentially. "I was trying to avoid the stereotypes," Spiegelman explained. "My Jew escaped from a Chagall painting; she was not of the Aunt Jemima school. A religious Jew couldn't touch his wife in public. I brought them together, and both sides were equally upset." He thought that embrace would be amusing, rather than upsetting.

Another cover, however, "41 shots 10 cents," (March 8, 1999) Spiegelman claims was "meant to shock." The white police officer in a shooting gallery made a clear reference to the Amadou Diallo shooting. "The cover brought it from a conversation only Al Sharpton was having and opened it up as a city-wide dialogue," said Spiegelman, who described the cover as "a picture of a picture of what happened to the image of the police."

Mouly took this idea of crossing a line one step further when she described the inspiration behind "The Politics of Fear" New Yorker cover (July 21, 2008) depicting candidate Barack Obama dressed as a Muslim and a rifle- and ammunition-toting Michele Obama fist-bumping in the Oval Office. "We were trying to pin down the whisperings," Mouly explained. "The power of the talk was that no one brought it out in the open. This was the right-wing nightmare."

What the cartoons of the prophet in Charlie Hebdo attempted to do, Mouly said, was to demonstrate that "there's a difference between the fundamentalists and Muhammad. They did not show [the prophet's] face." Crabapple also pointed out that "There's a Persian tradition of representing the prophet. There's also a solidarity [with Charlie Hebdo] from Middle Eastern journalists. The people on the front lines are not Western cartoonists, they're the writers of the global South."

"I have no interest in drawing the prophet--unless I'm told I cannot," added Manu. "Charlie Hebdo did things in context, not as an insult. It was political commentary." --Jennifer M. Brown

photos courtesy of PEN American Center

Maya Angelou will be honored with a Forever Stamp by the U.S. Postal Service, which said it will preview the stamp and provide details on the day and location of the first-day-of-issuance ceremony at a later date.

Maya Angelou will be honored with a Forever Stamp by the U.S. Postal Service, which said it will preview the stamp and provide details on the day and location of the first-day-of-issuance ceremony at a later date.

To help spur business in a city hit by multiple snowstorms over the past month, the Office of Economic Development in Boston, Mass., yesterday introduced "

To help spur business in a city hit by multiple snowstorms over the past month, the Office of Economic Development in Boston, Mass., yesterday introduced " In featuring the "

In featuring the " The Nurture Effect: How the Science of Human Behavior Can Improve Our Lives and Our World

The Nurture Effect: How the Science of Human Behavior Can Improve Our Lives and Our World Nothing much seems to be going on with Francis Falbo, the narrator of Adam Rapp's new novel, set in downstate Pollard, Ill., during the winter of Francis's 36th year. Former rhythm guitar player and songwriter for Third Policeman, his defunct "well-aged, anti-industry psychedelic semi-jam band with a penchant for outro pop harmonies and the occasional speedy punk vibe," Francis lives alone in the attic of his inherited Victorian childhood home converted to apartments. His beloved mother died slowly of cancer and his distant accountant father retired and moved to Florida with a bimbo 20 years his junior. After only three years of marriage, Francis's wife left him for a square-jawed New York pharma salesman. Francis isn't doing well. He sees himself as "the human equivalent of a cold rainy day... a brown puddle in the middle of a dead-end street, with maybe a Popsicle stick or two floating in my dank, dog-slobbered water." Withdrawn and agoraphobic, he lives on junk food, whiskey and pills from his home delivery drug dealer and wears worn slippers and a ratty bathrobe--rarely venturing outside during a Midwest season that begins with blizzards and ends with a devastating multi-tornado storm.

Nothing much seems to be going on with Francis Falbo, the narrator of Adam Rapp's new novel, set in downstate Pollard, Ill., during the winter of Francis's 36th year. Former rhythm guitar player and songwriter for Third Policeman, his defunct "well-aged, anti-industry psychedelic semi-jam band with a penchant for outro pop harmonies and the occasional speedy punk vibe," Francis lives alone in the attic of his inherited Victorian childhood home converted to apartments. His beloved mother died slowly of cancer and his distant accountant father retired and moved to Florida with a bimbo 20 years his junior. After only three years of marriage, Francis's wife left him for a square-jawed New York pharma salesman. Francis isn't doing well. He sees himself as "the human equivalent of a cold rainy day... a brown puddle in the middle of a dead-end street, with maybe a Popsicle stick or two floating in my dank, dog-slobbered water." Withdrawn and agoraphobic, he lives on junk food, whiskey and pills from his home delivery drug dealer and wears worn slippers and a ratty bathrobe--rarely venturing outside during a Midwest season that begins with blizzards and ends with a devastating multi-tornado storm.

Crabapple expanded on the idea of a line to be crossed: "There's the law that bans it, but then you're outsourcing your ethics to the State." She described her experience

Crabapple expanded on the idea of a line to be crossed: "There's the law that bans it, but then you're outsourcing your ethics to the State." She described her experience