_George_Mcluskie.jpeg) |

| photo: George Mcluskie |

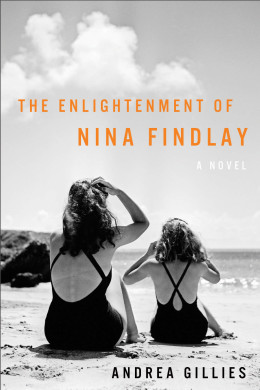

Andrea Gillies lives in Edinburgh, Scotland. Her debut book was the memoir Keeper: One House, Three Generations and a Journey into Alzheimer's (Broadway, 2010), which won the Wellcome Trust Book Prize and the Orwell Book Prize. The inspiration for her first novel, The White Lie (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt/Mariner), about three generations of a family, came to her while she was on a bus in the middle of the Highlands, traveling along a long stone estate wall, and she glimpsed a dilapidated old manor house through an overgrown garden. The Enlightenment of Nina Findlay (Other Press, May 5, 2015) is her second novel, written in the aftermath of her own separation and divorce.

On your nightstand now:

My nightstand is always overflowing. It gets to the point that I can't bear to remove books I know I'll never finish, or even start: the situation becomes almost superstitious. I've had to buy really big nightstands, and I've developed a sort of hierarchy in which the urgency of the need to read something is indicated by the title's position in the various piles. Currently in the pile at the front: Jessie Burton's The Miniaturist, Anne Tyler's A Spool of Blue Thread, Karen Joy Fowler's We Are All Completely Beside Ourselves, a battered 19th-century copy of Keats's poetry, Martin Gayford's A Bigger Message (about David Hockney) and a book about Barbara Hepworth, the subject of my novel after next.

Favorite book when you were a child:

I was a reading child, the kind with a book glued to her face at all possible times. I'd try to read at mealtimes, surreptitiously on my lap, and would be chastised. I'd read on the way to school, a 10-minute walk to the other side of the Yorkshire village where I grew up, and would walk into things. My first love was Enid Blyton's the Secret Seven series, after which I moved on to pony books by the Pullein-Thompson sisters. I read Ballet Shoes by Noel Streatfeild, probably a dozen times. By 11, I was starting on Jane Austen and Charles Dickens. It was a very English introduction to reading. My dad bought me hardbacks of books he'd loved.

Your top five authors:

This is as impossible a list as the Top Five Films/Tracks/Pictures, but off the top of my head, the five people who come to mind, whose books I might grab in a fire, are George Eliot (Middlemarch), Charlotte Bronte (Jane Eyre), Charles Dickens (especially for Great Expectations), Jane Austen (especially for Persuasion) and Edith Wharton, for everything. I'd have to place Henry James at #6, and then a whole load of modern American writers from #7 onwards. Can we do a top 25? I didn't get chance to mention Virginia Woolf or E.M. Forster. If I'm given a top five, I don't seem to be able to get out of the 19th century, and the writers I read and re-read when I was 16, 17. These people have a way of staying with you.

Book you've faked reading:

I don't think I've ever read a book by one of the great and revered Russians. I have editions on my shelves somewhere, waiting for me, and I've got to page 5 on several occasions, but I think I'm probably never going to read Anna Karenina. I've seen the movie, though, so I can fake it if I have to.

Book you're an evangelist for:

Book you're an evangelist for:

In terms of the one I'd urge anyone to read, suspecting they might not have done, Jane Eyre (Charlotte Bronte). No-one had done anything like this before: it was revolutionary in the development of the inner life of the novel. Bronte rejected the idea of the beautiful heroine, saying "I will show you a heroine as plain and small as myself." She was brave in using the voice of Jane to express how stifled women were by convention: "Women are supposed to be very calm generally: but women feel just as men feel; they need exercise for their faculties, and a field for their efforts, as much as their brothers do; they suffer from too rigid a restraint, too absolute a stagnation, precisely as men would suffer; and it is narrow-minded in their more privileged fellow-creatures to say that they ought to confine themselves to making puddings and knitting stockings, to playing on the piano and embroidering bags."

The story has very pleasing wish-fulfillment aspects: Rochester sees Jane's inner beauty and falls for her, despite her plainness and lowly social status. "He was the first to recognise me, and to love what he saw."

For me, it's probably the most flawless novel, in terms of its shape, development, language, its thoroughly imagined world, that was ever written. That's my pitch.

Book you've bought for the cover:

Alasdair Gray's Lanark, because he'd drawn all over it.

Book that changed your life:

Books have been milestones in my life since I was four years old, and I could tell you about a dozen turning points that books have signalled and embodied, but the one that made me have a go at writing fiction was Carol Shields's Republic of Love, which is a straightforward romantic novel made spectacular by beautiful phrases, by cadence and style. I wrote some of her wonderful metaphors down in a notebook. It made me realise that I could write in my own voice, and take an ordinary story and make it something memorable.

Favorite line from a book:

"We are such stuff as dreams are made on; and our little lives are ended with a sleep." It's from Shakespeare's The Tempest. No-one's ever written a better line.

Which character you most relate to:

In general I don't relate to characters in books, or seek to relate to them, or expect to. I'm not disappointed if I can't relate. I have this conversation with other people a lot. It seems to me a very modern expectation, to "relate" to people in books. Amazon is full of reader-critics complaining that they couldn't relate to anyone in the novel they're criticizing. I find that a strange way of reading. I don't relate to anyone in King Lear or David Copperfield and it doesn't stop them being consummate works of art.

But if forced to pick someone in a book to relate to, it would have to be Elizabeth Bennet in Pride & Prejudice. She speaks out, and has integrity, but is also deeply lovable. She was tremendously influential when I was an insecure teen.

Book you most want to read again for the first time:

It would have to be The Secret Seven (Enid Blyton) which was written in 1949 and which I was given for my ninth birthday in 1970. I got the whole set, and read them one after another, and then again, and again and again. I was absolutely transported. I longed to be in a secret society and do detective work and fight crime. I started keeping a notebook, noting down the characters in the neighbourhood and what they might be up to, and what their secret identities might be. I probably started being a novelist then. That's part of it, but the main reason I'd want to reread The Secret Seven again for the first time is so that I could be nine again, with my whole life ahead.

Dalkey Archive Press

Dalkey Archive Press Amazon plans to

Amazon plans to  Kobo is partnering with Global Eagle Entertainment, a media and connectivity provider to the travel industry, and Bauer Communications to

Kobo is partnering with Global Eagle Entertainment, a media and connectivity provider to the travel industry, and Bauer Communications to  Representatives from nearly 200 small businesses from across the country are in Washington, D.C., for the 2015

Representatives from nearly 200 small businesses from across the country are in Washington, D.C., for the 2015  On Saturday, May 16,

On Saturday, May 16,  No trip to New York City would be complete without a trip to Brooklyn, home to a thriving literary scene. Today DK Eyewitness Travel Guides is taking you on a tour from Greenpoint to Park Slope, stopping to talk with three local bookshops along the way.

No trip to New York City would be complete without a trip to Brooklyn, home to a thriving literary scene. Today DK Eyewitness Travel Guides is taking you on a tour from Greenpoint to Park Slope, stopping to talk with three local bookshops along the way. What's the number one thing people should do when in New York City for BEA?

What's the number one thing people should do when in New York City for BEA? Bookshop:

Bookshop:  Bookshop:

Bookshop:  The Familiar: Volume 1: One Rainy Day in May

The Familiar: Volume 1: One Rainy Day in May_George_Mcluskie.jpeg)

Book you're an evangelist for:

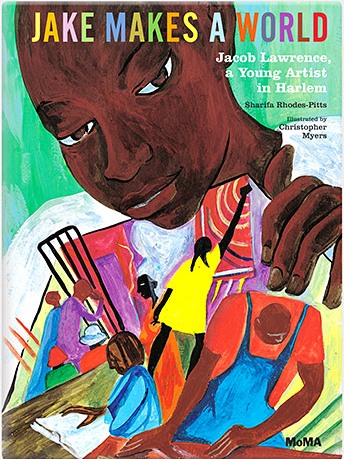

Book you're an evangelist for: For the first time since 1993, all 60 panels of The Migration of the Negro series by Jacob Lawrence (1917–2000) are reunited at New York's Museum of Modern Art. Lawrence created the series in 1941 at the age of 23; the odd-numbered panels are in the Phillips Collection's permanent holdings, and the even-numbered panels are part of the MoMA's permanent collection.

For the first time since 1993, all 60 panels of The Migration of the Negro series by Jacob Lawrence (1917–2000) are reunited at New York's Museum of Modern Art. Lawrence created the series in 1941 at the age of 23; the odd-numbered panels are in the Phillips Collection's permanent holdings, and the even-numbered panels are part of the MoMA's permanent collection.