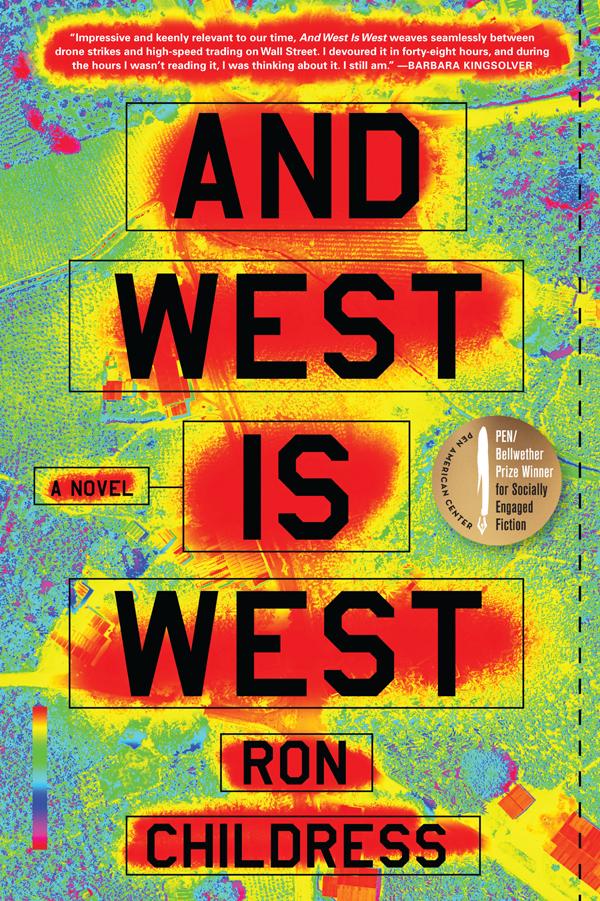

Ron Childress began publishing short stories in the 1980s. The manuscript of his debut novel, And West Is West, won the PEN/Bellwether Prize for Socially Engaged Fiction and was published by Algonquin Books on October 13, 2015. He originally planned to teach English literature and write fiction, but changed his career path after a year as a college adjunct. Moving from Florida to Washington, D.C., he worked as a writer/editor for a professional association and then as a copywriter/technical writer/programmer for a marketing company that served high-tech clients. And West Is West focuses on secrets--family, corporate, and military--and how they can go toxic. It also dramatizes how the technology can distance us from personal responsibility and enable destructive behavior.

On your nightstand now:

On my nightstand is Karl Ove Knausgaard's My Struggle: Book Four. The series is addictive, and I simply capitulated and set aside the time for it. On my nightstand's electronic device is Gustave Flaubert's L'Éducation sentimentale; I read a page or two a day to exercise my minimal French. To fill my Stairmaster time at the gym, the audiobook of Bryan Burrough's Days of Rage: America's Radical Underground, the FBI, and the Forgotten Age of Revolutionary Violence is giving me flashbacks to the bomb threats that regularly emptied my junior high school.

Favorite book when you were a child:

Daniel Defoe's Robinson Crusoe was a book that I enjoyed. The only child of a non-helicopter parent, I spent a lot of time reading, and books like Crusoe were my Friday. Also, I loved digging through our Funk & Wagnalls Universal Standard Encyclopedia and Yearbooks--I still have the set. It's a fascinating time capsule. The extensive entries on the literature of individual countries remind me of how central to our culture books, especially novels, used to be.

Your top five authors:

This list can change on any given day. Looking at my bookshelves right now, I am going to pick Henry James (my dissertation subject), Martin Amis (for his use of language), Doris Lessing (for the intensity of The Golden Notebook), Philip Roth (for his 1990s American trilogy) and J.M. Coetzee (for his austere descriptive power).

Book you've faked reading:

I'd be most likely to fib about Miguel de Cervantes's Don Quixote. It's an urtext so culturally pervasive that I often forget that I've never actually read it. Every time I use the phrase "tilting toward windmills," I experience a twinge of remorse.

Book you're an evangelist for:

Book you're an evangelist for:

Just about anything by Roberto Bolaño. But because his 2666 is monumental and uncompromising, this is the book I would challenge a reader to try. What pulls you through is Bolaño's narrative power, which he applies most hypnotically in a long section dedicated to female sweatshop workers who end as victims of Mexico's drug war. Bolaño's introductory CSI-like descriptions are disturbing, but then he goes on to portray the victims' quite individual lives before their tragedies. Bolaño's narrative refuses to allow these maquiladora workers to be diminished into statistics.

Book you've bought for the cover:

An intriguing cover will certainly lead me to pick up a book in a bookstore and go on to read its blurbs and first pages, so it could be the starting point of an "I'm sold." An early book that sold me because of its cover was Bernadette Mayer's Memory. In my 20s, I must have identified with the wrap-around full-bleed images of young bohemian life. They have the same pull as the photographs in Nan Goldin's later The Ballad of Sexual Dependency--which, in fact, the stream-of-consciousness prose-poetry in Memory could illustrate. I also first picked up Goldin's Ballad, in a Miami bookstore, because of its cover.

Book you hid from your parents:

It was an anthology: The Olympia Reader, edited by Maurice Girodias. Filled with excerpts from once-banned works by Henry Miller, William Burroughs, Jean Genet, J.P. Donleavy and several other writers of mixed ambition, it offered a young person a stimulating introduction into the wide range of human behavior. Today, of course, the Internet answers this function.

Book that changed your life:

Lust for Life, Irving Stone's biographical novel of Vincent van Gogh. It's the book that inaugurated my abiding fascination with visual art--a fascination that developed so thoroughly I ultimately married an artist.

Favorite line from a book:

What reader can have just one favorite line, which are so often first lines: "Call me Ishmael." --Herman Melville, Moby-Dick; "A screaming comes across the sky. It has happened before, but there is nothing to compare it to now." --Thomas Pynchon, Gravity's Rainbow. Or they may be lines within a first chapter: "This then? This is not a book. This is libel, slander, defamation of character." --Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer.

Outside of such classics, I would vote Zia Haider Rahman's In the Light of What We Know as having as high a percentage of quotable lines as any recent fiction. Here is one of my favorites: "Watching him vanishing into the multitude, I had the impression that this is what adult life consists of, encounters with people who are impermanent and want something, and that I, like everyone else, am only a cameo in the lives of others." Or how about, "Like apes knuckling down to a forest clearing to groom each other, they thronged to the drinks parties and dinner parties, the art openings and first nights." Or perhaps Rahman's concise explication of his title is my favorite: "Everything new is on the rim of our view, in the darkness, below the horizon, so that nothing new is visible but in the light of what we know."

Five books you'll never part with:

Herman Melville's Moby-Dick, William Gaddis's The Recognitions, Fyodor Dostoyevsky's The Adolescent, James Joyce's Ulysses, and Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn's The Gulag Archipelago are books I consumed in my late teens to early 20s, and which I think about fondly, and which I happily display on my bookshelves as early reading accomplishments.

Book you most want to read again for the first time:

Gabriel García Márquez's One Hundred Years of Solitude. Although, whenever I read the opening lines about Aureliano Buendía's first encounter with ice, the chill of pleasure is so great that I almost feel as if I am reading it for the first time.

.jpg)

In the third quarter ended September 30, net sales at Amazon rose 23.2%, to $25.4 billion, and net income was $79 million, compared to a net loss of $437 million in the same period a year earlier.

In the third quarter ended September 30, net sales at Amazon rose 23.2%, to $25.4 billion, and net income was $79 million, compared to a net loss of $437 million in the same period a year earlier.

In the months since

In the months since  Face Paint: The Story of Makeup

Face Paint: The Story of Makeup

Book you're an evangelist for:

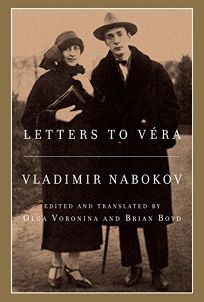

Book you're an evangelist for: Véra Nabokov was the wife and assistant to the great Russian expatriate novelist Vladimir Nabokov. She was his closest confidante and adviser, and his grandest love. Almost all of these previously unpublished Letters to Véra are from the years 1923 to 1950, throughout their courtship and the first and most difficult half of their marriage. After that, during the years of Vladimir Nabokov's greatest literary fame, they were rarely separated and had no need to correspond.

Véra Nabokov was the wife and assistant to the great Russian expatriate novelist Vladimir Nabokov. She was his closest confidante and adviser, and his grandest love. Almost all of these previously unpublished Letters to Véra are from the years 1923 to 1950, throughout their courtship and the first and most difficult half of their marriage. After that, during the years of Vladimir Nabokov's greatest literary fame, they were rarely separated and had no need to correspond.