_Cristin_Young_(Medium).jpg) |

| photo: Cristin Young |

Sophie Egan is director of programs and culinary nutrition for the Strategic Initiatives Group at the Culinary Institute of America. She's also a contributor to the New York Times's Well blog, and has written about food and health for KQED, WIRED and Sunset magazine, where she worked on The Sunset Cookbook and The One-Block Feast. She holds a master's of public health from the University of California, Berkeley, with a focus on health and social behavior, and a bachelor of arts with honors in history from Stanford University. Egan's new book is Devoured: From Chicken Wings to Kale Smoothies--How What We Eat Defines Who We Are (Morrow, May 3, 2016). It's a well-researched, fascinating and witty discussion about food and American culture.

You write about the correlation between productivity and the number of hours worked. How has this shaped our eating habits?

We have a "more is better" approach to work, especially in tech. The floodgates have been flung open as to what is a reasonable time spent working. There used to be more time for other things, but now we think that if you can work, why wouldn't you? You have Internet access, you have more to be done--so we don't focus on food during the day. We spend the least amount of time of all OECD [Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development] countries in preparing food. We spend about an hour and 20 minutes a day eating, half an hour less than in those countries. We're using food as fuel.

But we still want it to taste good.

We do, right. We've always been a culture to eat on the run, but now there's a greater availability than ever of portable, delicious snack foods, and that is enabling the heightened emphasis on extreme working.

We want things easier tomorrow than they are today; we want meals that microwave in three minutes instead of four. We want things to taste good, but we will absolutely compromise on freshness and some percentage of deliciousness for convenience and speed.

America has an obsession with protein; we think we need more than we actually do.

The Paleo diet, and men, are driving this a lot, particularly with meat. Grams of protein is one of the top things people look for on labels. It's a response to our previous low-fat obsession--all these foods had fat stripped out, which was replaced by additives and sugar and salt. So people were basically eating refined carbs. When people discovered that eating, say, a handful of nuts made them feel full for a while longer, they thought protein was the answer to getting through a crazy hectic day, instead of the instant energy from a cookie and the subsequent crash. And, as a culture, we have this tendency to jump on whatever the new nutritional darling du jour is. Now it's protein's turn. We have a fitness-focused culture and people are into muscle building and leanness. Athletes need more protein for sure, but now people think they need outrageous amounts compared to what they actually need.

Is there a downside to focusing on protein?

Some of the concern is that you don't store protein. So you are putting excess stress on your kidneys, but we don't know yet what that level is--what's optimal, what's harmful. But it has set up an entire industry--I just saw "protein water" in a store! That cracked me up. And so many products that already have protein now are advertised as "protein-packed," like peanut butter. Or Cheerios with added protein. Well, the difference between that and regular Cheerios might be half a gram per serving, but it costs more.

It's concerning to me the ways nutrition frenzies cause us to always jump to the extreme.

I liked the chapter about "cheffing"--adding something extra to personalize your meal, while denying the reality of processing and preparation.

I liked the chapter about "cheffing"--adding something extra to personalize your meal, while denying the reality of processing and preparation.

Absolutely. That's why so many of these make-it-your-own/fast-casual concepts, like Subway, are just going gangbusters. People want their food fast and they want it at a good price. But they want to feel like someone made it for them, like at Starbucks where they call your name out for a drink that was specially crafted for you. We feel we deserve our food to be special. We will pay a small premium to meet these desires--to add tomato to a sub--and to have food delivered.

Brunch--in your words, our secular church--has become a time for community, a time to relax. And a time to eat a lot of food you wouldn't normally eat--a "free day."

I really enjoyed that chapter. Initially I wondered if it was just a San Francisco thing, or a Seattle thing [Egan is from Seattle], and it's really not. It's widespread, and what does fascinate me is the way that it's a craving for community. It used to be a normal way of eating but now represents a large gulf in people's lives around social, even guilt-free, eating. There's so much denial-based eating, but on Sunday you can have chicken and waffles and gravy and it doesn't count.

Would you explain the concept and the success of selling absence?

This is where food companies label foods based on what the foods don't have: gluten-free, low fat, reduced calories, non-GMO, etc. It very much plays into our lack of food literacy. In my view, it's about the way in America where we default to the latest nutrition study. We don't really know what's in a certain cereal or nutrition bar, but we know we want to avoid something. So we look to those labels to tell us what a food's value is, a signal that it's safe to proceed. And "natural" has come to mean the absence of stuff we don't want in our food.

One of the things we miss when we focus on what is taken out is what is put in. When fat is taken out, sugar and salt are added for flavor.

Absolutely. We definitely overlook that. Michael Moss, in Salt Sugar Fat, goes into that in great detail. It's happening now with a lot of gluten-free products. If you look at the ingredients list in a gluten-free pastry, it takes up most the page--whether for texture or for shelf life, there's got to be something in the pastry to take up the slack.

Or take Cheerios. The label says "no GMOs." But oats aren't GMO grains. A lot of foods that never had gluten to begin with say "gluten-free."

Exactly. It illustrates two things about American food culture. There's an enormous amount of fear-mongering that happens, and it keeps us in the grasp of the food companies, because if we don't understand food, then we are relying on their labeling and their health claims. And then there is the ongoing outsourcing of food preparation and creation. But this is very American: on the positive side, we welcome new foods and food experiences; the flip side is that we don't have the common sense, the core familiarity with food that can be carried on from one generation to the next. No stability. It leaves us at the whimsy of the latest health freak-out and corresponding food labeling.

Instead of cooking, we are outsourcing our food more and more. What are the consequences?

One consequence is the growing distance from the origin of food and what is in it. The grocery store has more and more space for prepared foods, it's harder and harder to have a reason to cook. We are going to be further dependent on whatever new flashy things come out of the industry, we aren't really in the driver's seat. Also, from a food and culinary literacy standpoint, it means we aren't passing down some of the muscle memory you get from using a knife, beating eggs. If you learn these things from an early age, you have skills, you have empowerment for life--you can throw together whatever is around and make an omelet. It's concerning to think about a future where people don't have these skills or that knowledge, or an ease with feeding yourself.

You note that the Vatican consumes more wine per capita than anyplace else. And that here, our wine capital is Washington, D.C. That explains so much....

Well, House of Cards....

After 14 years owning Point Reyes Books, Point Reyes Station, Calif., Kate Levinson and Steve Costa are putting the store up for sale.

After 14 years owning Point Reyes Books, Point Reyes Station, Calif., Kate Levinson and Steve Costa are putting the store up for sale..jpg)

BINC.1118.T2.2024YEARENDCAMPAIGN.jpg)

The Book Spot

The Book Spot Among attendees last week at BookExpo America in Chicago was a familiar face to veteran booksellers: Bernie Rath, executive director of the American Booksellers Association from 1984 to 1997, who hadn't attended the show in many years. Rath, who lives in Florida now, came in part because he has published two books in the past two years. (Google "Florida Gunkholer," he said, "if you're interested in water, nature, islands, beaches and outdoor adventures and funny things.")

Among attendees last week at BookExpo America in Chicago was a familiar face to veteran booksellers: Bernie Rath, executive director of the American Booksellers Association from 1984 to 1997, who hadn't attended the show in many years. Rath, who lives in Florida now, came in part because he has published two books in the past two years. (Google "Florida Gunkholer," he said, "if you're interested in water, nature, islands, beaches and outdoor adventures and funny things.")

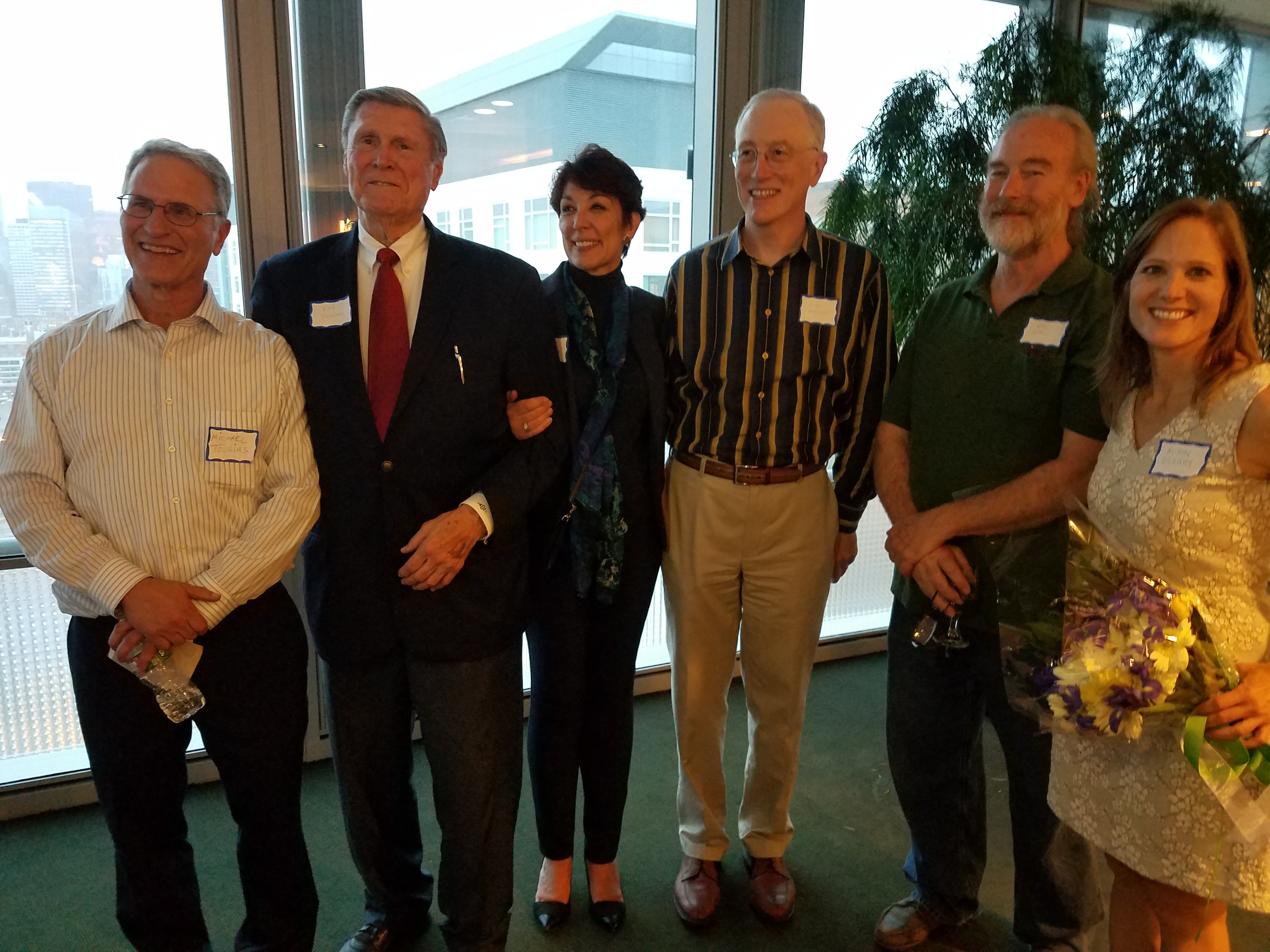

Pegasus Books hosted a launch party at the John Hancock Tower in Boston for So Close to Home: The True Story of an America Family's Fight for Survival During World War II by Michael Tougias (The Finest Hours) and Alison O'Leary. Proceeds from the event benefited the Greater Boston Food Bank. Pictured (l.-r.): Tougias; U-boat torpedo survivor Ray "Sonny" Downs (whose family's story is featured in the book); Downs's friend Lynne; John Hancock legal counsel Jim Hoodlet; Roy Sorli Jr. (son of the Merchant Mariner who saved Downs's 11-year-old sister, Lucille); and O'Leary.

Pegasus Books hosted a launch party at the John Hancock Tower in Boston for So Close to Home: The True Story of an America Family's Fight for Survival During World War II by Michael Tougias (The Finest Hours) and Alison O'Leary. Proceeds from the event benefited the Greater Boston Food Bank. Pictured (l.-r.): Tougias; U-boat torpedo survivor Ray "Sonny" Downs (whose family's story is featured in the book); Downs's friend Lynne; John Hancock legal counsel Jim Hoodlet; Roy Sorli Jr. (son of the Merchant Mariner who saved Downs's 11-year-old sister, Lucille); and O'Leary. Katz noted that one reason for the recent comeback of independent bookstores nationwide is people like Brooks, who "are a new kind of bookstore owner. They understand business as well as literature, they make good decisions and keep an eye on the cash flow as well as the bestsellers. They love books, but they also learned from Amazon: customer service is not just about having books in the store, it is about knowing customers, treating them well, making them feel safe and comfortable and giving them what they want....

Katz noted that one reason for the recent comeback of independent bookstores nationwide is people like Brooks, who "are a new kind of bookstore owner. They understand business as well as literature, they make good decisions and keep an eye on the cash flow as well as the bestsellers. They love books, but they also learned from Amazon: customer service is not just about having books in the store, it is about knowing customers, treating them well, making them feel safe and comfortable and giving them what they want.... The Last Goodnight: A World War II Story of Espionage, Adventure, and Betrayal

The Last Goodnight: A World War II Story of Espionage, Adventure, and Betrayal_Cristin_Young_(Medium).jpg)

I liked the chapter about "cheffing"--adding something extra to personalize your meal, while denying the reality of processing and preparation.

I liked the chapter about "cheffing"--adding something extra to personalize your meal, while denying the reality of processing and preparation.  Ben Ehrenreich's The Way to the Spring: Life and Death in Palestine is a work of nonfiction journalism written with the lyrical passion of a novelist. His two previous books were novels--Ether and The Suitors; for his first nonfiction book, Ehrenreich spent three years embedded with Palestinian families living in the West Bank. In the introduction, he writes: "I do not aspire in these pages to objectivity. I don't believe it to be a virtue, or even a possibility. " He aspires, instead, to "something more modest than objectivity, which is truth." The Way to the Spring is unapologetically on the side of the Palestinian people, marshalling facts, history, anecdote and personal experience in order to persuade the reader to the author's point of view. That does not mean, however, that Ehrenreich's book is interested only in proving rhetorical points. Instead, The Way to the Spring functions primarily as an extraordinary love letter to a people that, through everything, persist.

Ben Ehrenreich's The Way to the Spring: Life and Death in Palestine is a work of nonfiction journalism written with the lyrical passion of a novelist. His two previous books were novels--Ether and The Suitors; for his first nonfiction book, Ehrenreich spent three years embedded with Palestinian families living in the West Bank. In the introduction, he writes: "I do not aspire in these pages to objectivity. I don't believe it to be a virtue, or even a possibility. " He aspires, instead, to "something more modest than objectivity, which is truth." The Way to the Spring is unapologetically on the side of the Palestinian people, marshalling facts, history, anecdote and personal experience in order to persuade the reader to the author's point of view. That does not mean, however, that Ehrenreich's book is interested only in proving rhetorical points. Instead, The Way to the Spring functions primarily as an extraordinary love letter to a people that, through everything, persist.