You think that their

dying is the worst

thing that could happen.

Then they stay dead.

Grief is a funny thing. I thought about beginning this column with the previous sentence, then decided not to, then decided I would after all because grief is funny, as in perplexing and mystifying and singular. Anyone who has experienced deep personal loss understands this, but an occasional reminder somehow always has the power to stun and haunt anew. This happened to me recently during a bookstore author event.

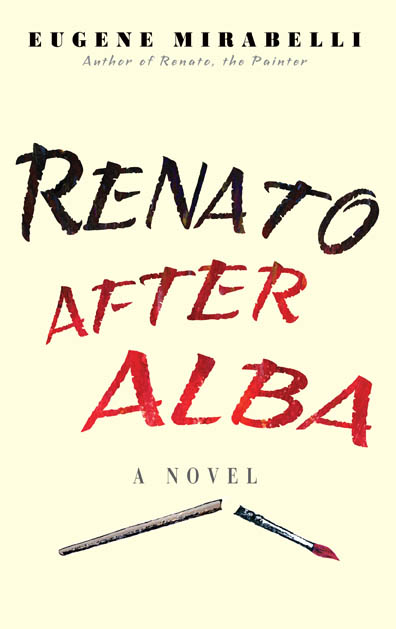

November 4 of this year was proclaimed Eugene Mirabelli Day in Albany, N.Y. In her proclamation, Mayor Kathy M. Sheehan noted that in his most recent book, Renato After Alba--a sequel to his 2012 novel Renato, the Painter (both published by McPherson & Co.)--the 85-year-old author "touches upon universal aspects of human existence by creating lovably flawed characters who subtly express the full range of human emotion and experience, from great joy to crushing loss, from deep love of life to rage against the inevitability of death. All written with clarity and cleverness and craft."

November 4 of this year was proclaimed Eugene Mirabelli Day in Albany, N.Y. In her proclamation, Mayor Kathy M. Sheehan noted that in his most recent book, Renato After Alba--a sequel to his 2012 novel Renato, the Painter (both published by McPherson & Co.)--the 85-year-old author "touches upon universal aspects of human existence by creating lovably flawed characters who subtly express the full range of human emotion and experience, from great joy to crushing loss, from deep love of life to rage against the inevitability of death. All written with clarity and cleverness and craft."

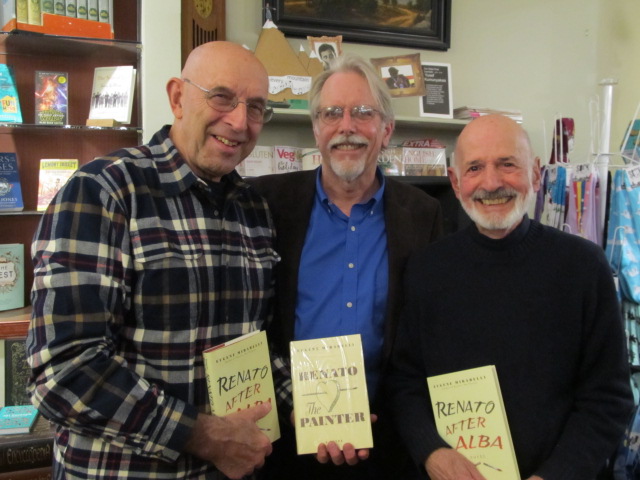

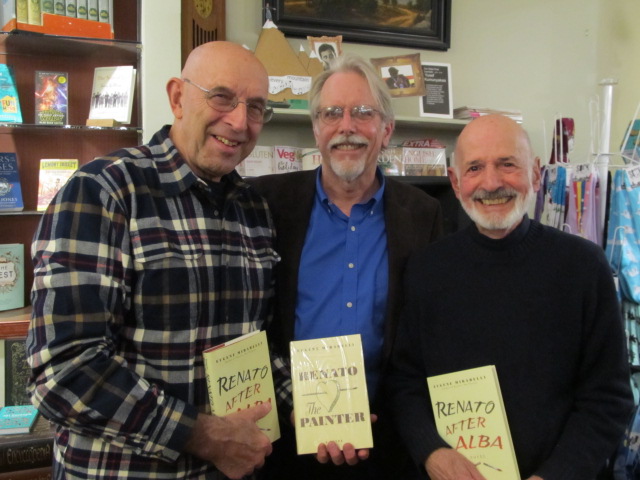

As part of the celebration, the Book House at Stuyvesant Plaza hosted an event last Friday, with renowned author Joseph Bruchac interviewing Mirabelli. I stopped by the bookstore to learn more about Renato Stillamare before--and after--Alba, but what I heard was something extraordinary about how one writer mourns... and works.

When I read Mirabelli's two novels back to back not long ago, I was struck by how intricately, and intimately, woven together they were, despite being in many ways quite different reads. Renato, the Painter's narrator is a 70-year-old scoundrel of an artist, still hungry for fame and not particularly averse to temptation. In the sequel, Renato is 12 years older and trying to reorient himself after the loss of his beloved wife, Alba, a striking presence in the first book and a stunning absence in the second. The borderline between these two novels is life and death.

"Anybody who's written a first-person novel knows that you're going to be identified with the narrator," Mirabelli told his audience. "My wife died after I'd written the book that precedes it. She had read everything in that first Renato book. We were about to go down and see the publisher, in fact, when she passed away. And I had a great sense of revulsion against that Renato, the Painter because I knew instinctively that people were going to identify me with him and I hated the idea. I took the galleys of the book and threw them in the garage, which is usually the stop that precedes being thrown away entirely. And it took about a year before the publisher and I got together and went ahead with that publication."

|

| Joseph Bruchac, Bruce McPherson & Eugene Mirabelli |

Although he acknowledged that he could have written a memoir after his wife's death, Mirabelli recalled that "for two or three years I didn't feel like writing at all. And my friends said, 'Oh you're a writer, you'll write.' That was the last thing on my mind. I did after a few years come to the point where I wanted.... not to write so much, but I wanted to have the feeling I used to have when I did have a piece of work I was writing. I really liked that feeling and wanted it back again.

"And sooner or later I did write a short story and another short story, but whenever I sat down to write my head was suddenly filled with death, and it became apparent finally that I couldn't write anything unless I wrote something about death. Something about grief. So the question was what.... And one of the things that had happened to me during that early period, very early, was the recognition that what happened to me, which astonished me, was happening to people every day. All over the globe. I wasn't unique at all. Grief is a strange emotion.... But grief is something you've never felt unless somebody you love has died. It's a remarkably unique emotion.... One of the curious things is how similar people's experiences can be while being unique in all the details."

Mirabelli added: "It's funny, or ironic that when I wrote Renato, the Painter, I decided that I wanted to write a really life-affirming book. At the end of that book, everybody who could possibly get pregnant is pregnant. I wanted that. Renato is a deeply flawed, but very creative person. I think it's a life-affirming story.... I didn't intend to write this book. No one would ever intend to write a book like Renato After Alba. But when I did start to write it, it was kind of weird... I went back to Renato, The Painter and there were all sorts of things that I found in the book that made sense in this book. And I don't know how that happened, but it just happened."

His publisher, Bruce McPherson, told me: "I've been working with Gene for about five years, and, for whatever reason, I think he's been an underrated and unjustly overlooked author for too long. Renato Stillamare is a remarkable creation, the literary offspring of a comic tradition dating at least from Fielding's Tom Jones through Joyce Cary's The Horse's Mouth and Donleavy's The Ginger Man, with a touch of John Kennedy Toole's A Confederacy of Dunces. But for all of his irrepressible life force and cranky artistic sprezzatura in Renato, the Painter, Renato is most completely realized and fully human in Renato After Alba, where he ultimately overcomes terrible suffering with wonderment toward life and creation. I now see the two books as necessary to one another, a perfect balance."

Grief is a funny thing.

Guide to Kulchur

Guide to Kulchur

Edwidge Danticat (left) visited

Edwidge Danticat (left) visited  Congratulations to

Congratulations to

The Italian government has launched an initiative to give a

The Italian government has launched an initiative to give a  Living Out Loud: Sports, Cancer, and the Things Worth Fighting For

Living Out Loud: Sports, Cancer, and the Things Worth Fighting For

Book you're an evangelist for:

Book you're an evangelist for: Set in 1962 Dublin, Ireland, The Magdalen Girls by V.S. Alexander revolves around three girls from different families committed by their parents to life at the Sisters of the Holy Redemption convent. Teagan Tiernan is accused of seducing a priest, Nora Craven is believed to have thrown herself at the boys, and Lea is a bit odd and had no place to live with her stepfather once her mother died. Denied contact with the outside world, forced to work in the hot and humid laundry with the other Magdalens or repair torn lace, the girls form an alliance and plot to escape their holy prison, but their keepers are diligent in their endeavors to flush the sins from these new charges.

Set in 1962 Dublin, Ireland, The Magdalen Girls by V.S. Alexander revolves around three girls from different families committed by their parents to life at the Sisters of the Holy Redemption convent. Teagan Tiernan is accused of seducing a priest, Nora Craven is believed to have thrown herself at the boys, and Lea is a bit odd and had no place to live with her stepfather once her mother died. Denied contact with the outside world, forced to work in the hot and humid laundry with the other Magdalens or repair torn lace, the girls form an alliance and plot to escape their holy prison, but their keepers are diligent in their endeavors to flush the sins from these new charges.

November 4 of this year was proclaimed Eugene Mirabelli Day in Albany, N.Y. In her proclamation, Mayor Kathy M. Sheehan noted that in his most recent book,

November 4 of this year was proclaimed Eugene Mirabelli Day in Albany, N.Y. In her proclamation, Mayor Kathy M. Sheehan noted that in his most recent book,