"But slowness is also essential to grasping the experience of modernity--if only because the hallmark of modernity is speed." --Arden Reed, Slow Art: The Experience of looking, Sacred Images to James Turrell

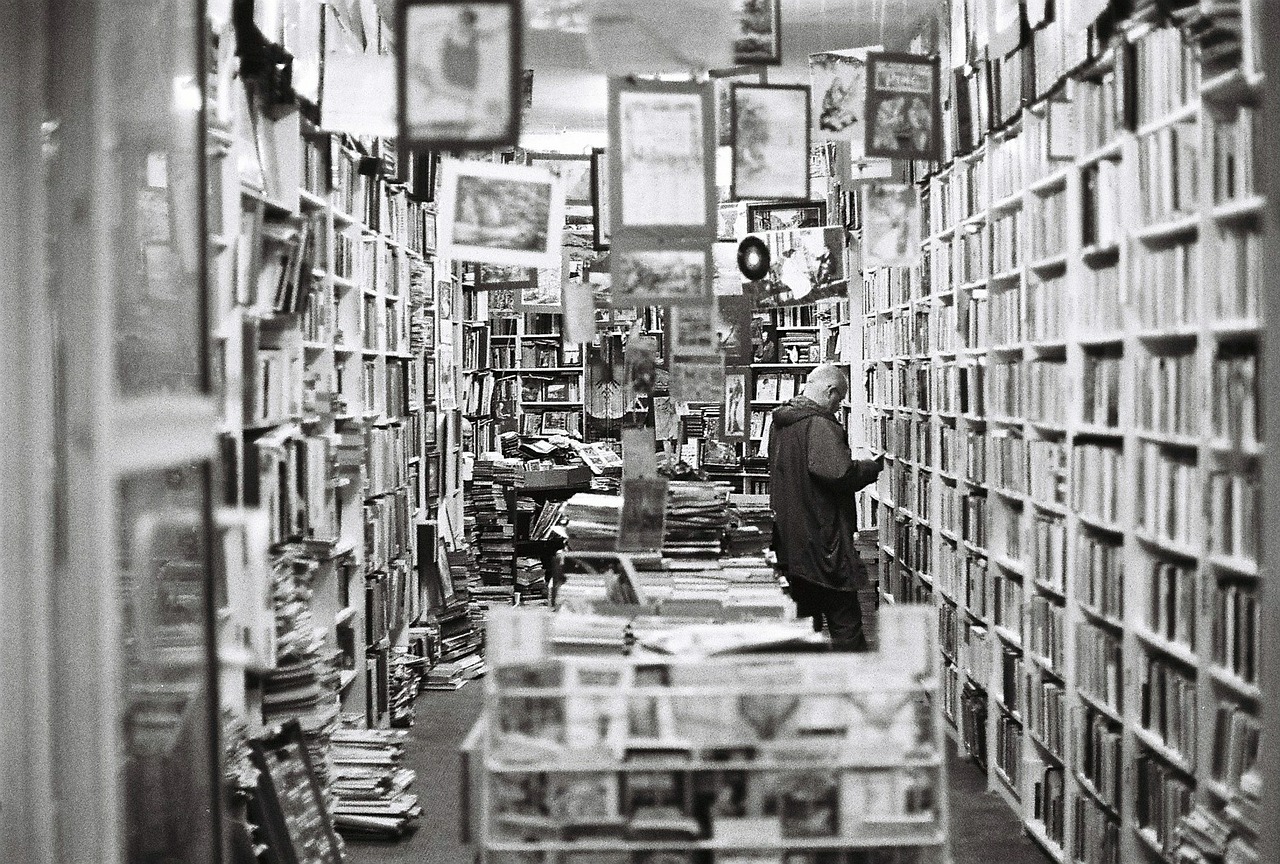

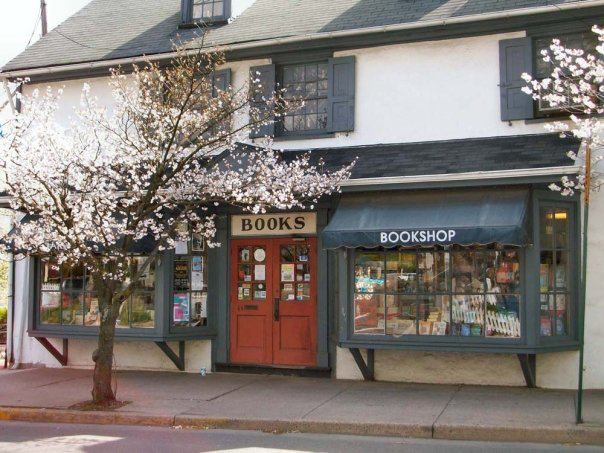

I'm reading Slow Art, which has somehow inspired me to think about bookshops, or more specifically the walls and aisles of shelves lined with titles and how we interact with them. Slowly, with focus.

I'm reading Slow Art, which has somehow inspired me to think about bookshops, or more specifically the walls and aisles of shelves lined with titles and how we interact with them. Slowly, with focus.

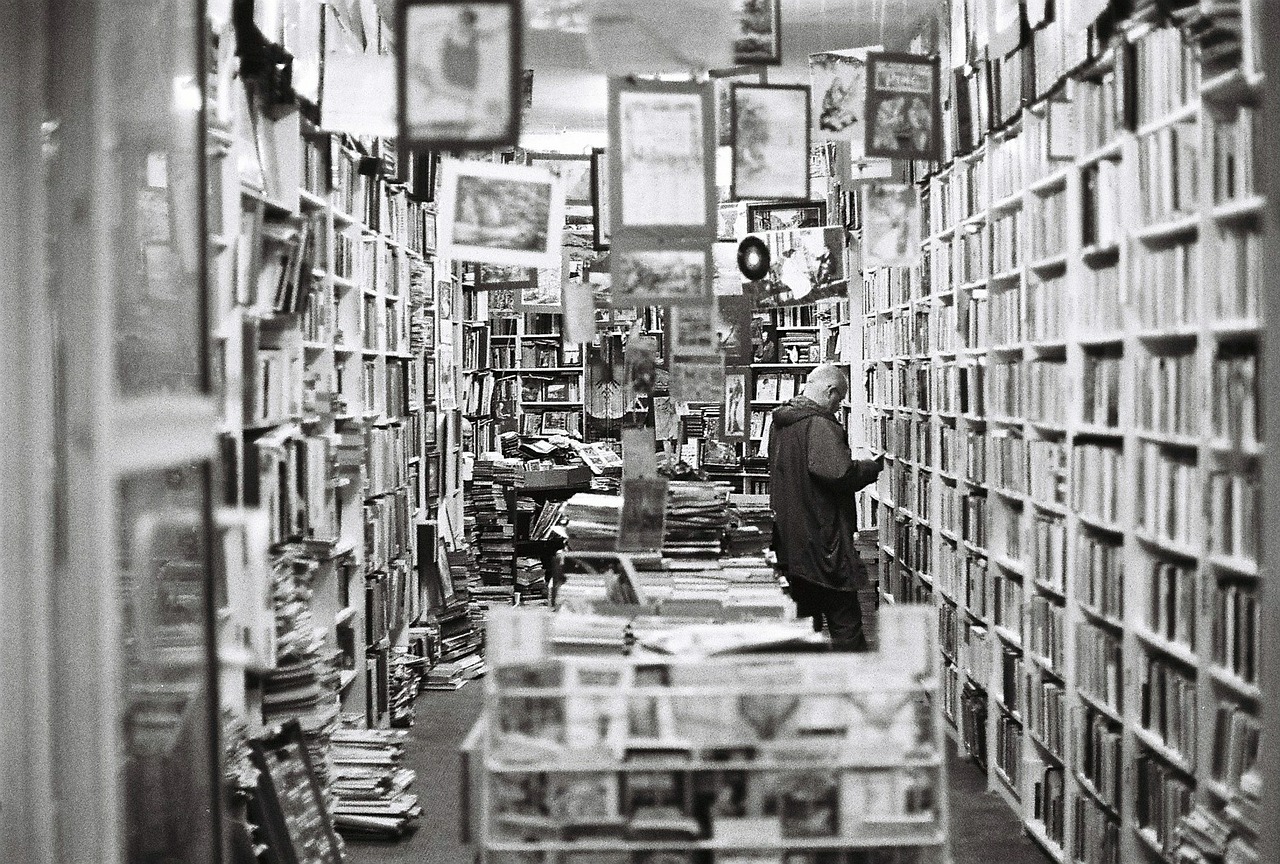

Bookshop as a museum? Bookshelves as art? Why not?

The genesis of Slow Art was Reed's personal response, over the course of eight years, to Édouard Manet's painting "Young Lady in 1866": "Gradually I came to understand that the image displayed--or, better, performed--a certain mystery. Not the hidden, but the visible.... I found myself drawn to the picture, resisted by it, and then drawn back. How long, I mused, could I sustain this conversation? I hardly thought about where I was being led, and certainly never imagined how often I would return to the spot, whether in my imagination or in fact."

Again, I think of bookshops. As a bookseller, I seldom had the luxury of engaging with the stacks in such a conversation. My encounters were often brief, practical chats about shelving, dusting, straightening, ordering or culling.

But in the decade since I reclaimed my role as bookstore customer, I've also regained the ability to slow time in the presence of a wall of books; see the whole; move in for a closer look at the spines, scanning titles with that signature head-tilt; pull a book from the installation and examine it; sit in a nearby chair and read a passage before returning it to the shelf; step back and see the broader canvas again.

"When life is tumbling out of control, I go to my happy place, where I can dream, remember and find order in chaos: I gaze upon my bookshelves," Patrick Barkham wrote this week in the Guardian.

"When life is tumbling out of control, I go to my happy place, where I can dream, remember and find order in chaos: I gaze upon my bookshelves," Patrick Barkham wrote this week in the Guardian.

This slow engagement can also be focused on a single book. In a recent Quartz essay, Thu-Huong Ha made the case for "the ultra slow site-specific read," observing that "the active ritual of reading one book extremely slowly, patiently, in the same place, over an unreasonably long time, has changed the way I see. It's a measured meting out of a book, like nibbling one piece of chocolate each night in the same chair over a year. It's a refusal to hurry up or to turn reading into a life hack; it's the anti-summer reading, the anti-binge read. It's site-specific, intensely slow reading, for no other reason than to bask in what's good."

By contrast, the Wall Street Journal reported last week that "speed listening" to podcasts is now a thing, with impatient listeners bumping programs up 1.5x, 2x and even 3x normal speaking pace: "The average podcast listener gets through five a week, says Edison Research, which studies media. People who listen most, the 21% squeezing in six or more, tend to listen fastest."

Slow down, you're moving too fast. Summer may be the best time to make a case for taking your foot off the reading pedal. Isn't languor a synonym for "summer read"?

Another question: "What happens when we run out of time?" asked Mads Holmen in Monday's edition of the Bookseller. "This might sound like a philosophical question, but with the explosion in content and entertainment offerings such as social media and freemium games, we are rapidly approaching a state of peak attention. I define peak attention as the moment where the competition for our attention reaches a saturated point--when there is no more time to spare and something else must miss out."

WWDD? (What would DeLillo do?) Near the end of Point Omega, a woman and a man study Douglas Gordon's video installation "24 Hour Psycho," which projects the Hitchcock classic film on a translucent screen and slows it down to the duration of a full day. "She told him she was standing a million miles outside the fact of whatever's happening on the screen," DeLillo writes. "She liked that. She told him she liked the idea of slowness in general. So many things go fast, she said. We need time to lose interest in things."

I saw Gordon's work at MoMA in 2006, the same year I happened upon Carsten Höller's "Amusement Park" at MASSMoCA. That installation featured refurbished carnival rides moving at barely discernible speeds. Museum director Joseph Thompson said: "Although this work is experienced through sight and sound, our staff has been surprised how visceral and physical the effect can be. Your body enters a space of shifting times and places, and your mind follows."

In Slow Art, Reed asks: "Is there a particular kind of art, whether still or moving, that compels rapt attention, or at least cultivates patience, that can lead us to look carefully, indulgently--even, [Peter] Sellars would say, with love?"

Yes.

I'm no art critic; I barely know what I like. But I do know there's a deep connection between the art and the books in my life. Whenever I'm in a bookshop, I turn my attention to book installations and the slow conversation begins again. --Robert Gray, contributing editor (Column archive available at Fresh Eyes Now)

Physicians Eileen Bobek and Natalya Miller opened Rebel Heart Books, Jacksonville, Ore., on July 10. Bookselling This Week reported that in February, they teamed up to purchase the Martin-Zigler building, "an historic blacksmith's building from the 1800s, which is located on the town's main drag, California Street. The store is a 625-square-foot space within the building, which also contains 300 square feet for storage and an office."

Physicians Eileen Bobek and Natalya Miller opened Rebel Heart Books, Jacksonville, Ore., on July 10. Bookselling This Week reported that in February, they teamed up to purchase the Martin-Zigler building, "an historic blacksmith's building from the 1800s, which is located on the town's main drag, California Street. The store is a 625-square-foot space within the building, which also contains 300 square feet for storage and an office."

NPR Books

NPR Books

Congratulations to

Congratulations to  Budget airline easyJet has launched a "

Budget airline easyJet has launched a " Happiness: The Crooked Little Road to Semi-Ever After

Happiness: The Crooked Little Road to Semi-Ever After

Book you're an evangelist for:

Book you're an evangelist for: The six stories in Paul Yoon's (Snow Hunters) second collection, The Mountain, are almost shocking in their simplicity. Possessing a fable-like sensibility, each one is a quietly elegant examination of how survivors of various sorts carry on in the face of profound loss. Yoon's strikingly uninflected prose heightens both the tension and the resonance of these tales.

The six stories in Paul Yoon's (Snow Hunters) second collection, The Mountain, are almost shocking in their simplicity. Possessing a fable-like sensibility, each one is a quietly elegant examination of how survivors of various sorts carry on in the face of profound loss. Yoon's strikingly uninflected prose heightens both the tension and the resonance of these tales.

I'm reading Slow Art, which has somehow inspired me to think about bookshops, or more specifically the walls and aisles of shelves lined with titles and how we interact with them. Slowly, with focus.

I'm reading Slow Art, which has somehow inspired me to think about bookshops, or more specifically the walls and aisles of shelves lined with titles and how we interact with them. Slowly, with focus.  "When life is tumbling out of control, I go to my happy place, where I can dream, remember and find order in chaos: I

"When life is tumbling out of control, I go to my happy place, where I can dream, remember and find order in chaos: I