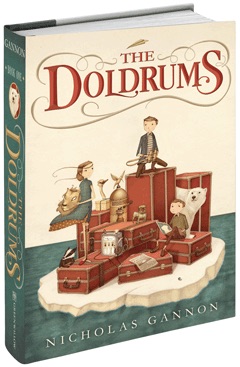

The Doldrums

by Nicholas Gannon

In Nicholas Gannon's debut novel, The Doldrums, an isolated boy longs for adventure and discovers that friendship offers the most excitement of all.

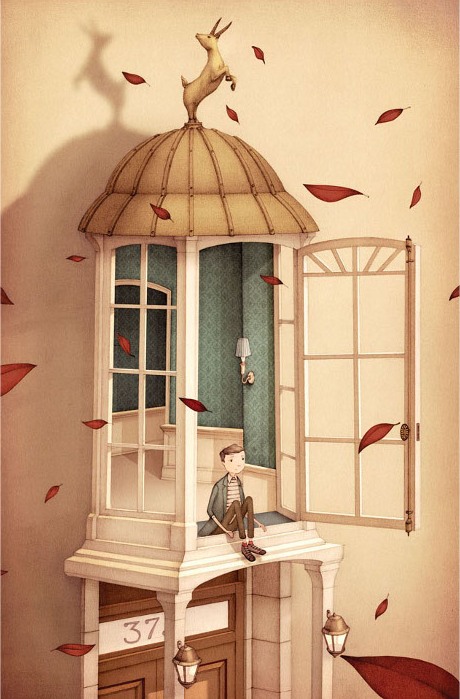

Eleven-year-old Archer is part of the Helmsley family, best known for his grandparents, Ralph and Rachel Helmsley, explorers extraordinaire who disappeared in Antarctica two years ago. But Archer's mother, who married into the family, fears that the boy has his grandparents' "tendencies, as she so often put it," and rarely permits him to step outside the house at 375 Willow Street, except to attend Willow Academy. Still, he manages to louse up his mother's parties when he leaves a taxidermied porcupine on a chair for an unsuspecting cocktail party guest and, at a dinner party, a staged scene with a stuffed polar bear causes his teacher, Mrs. Murkley ("a rather bulbous woman with little neck to spare"), to be carried out by paramedics. His mother is horrified; his father slightly amused.

Gannon's colored-pencil drawings, as smoothly layered and polished as watercolor paintings, endow the house with a character all its own. Indeed, readers may wonder why Archer would ever want to leave. The taxidermied animals talk (at least to Archer) and the rooms seem endless. He creates an oasis behind the houses where gardens thrive, protected from the busy streets. Still, Archer feels like a "prisoner" and can't shake the words of a party guest who claimed to know his grandparents: "Always remember you're a Helmsley, Archer. And being a Helmsley means something."

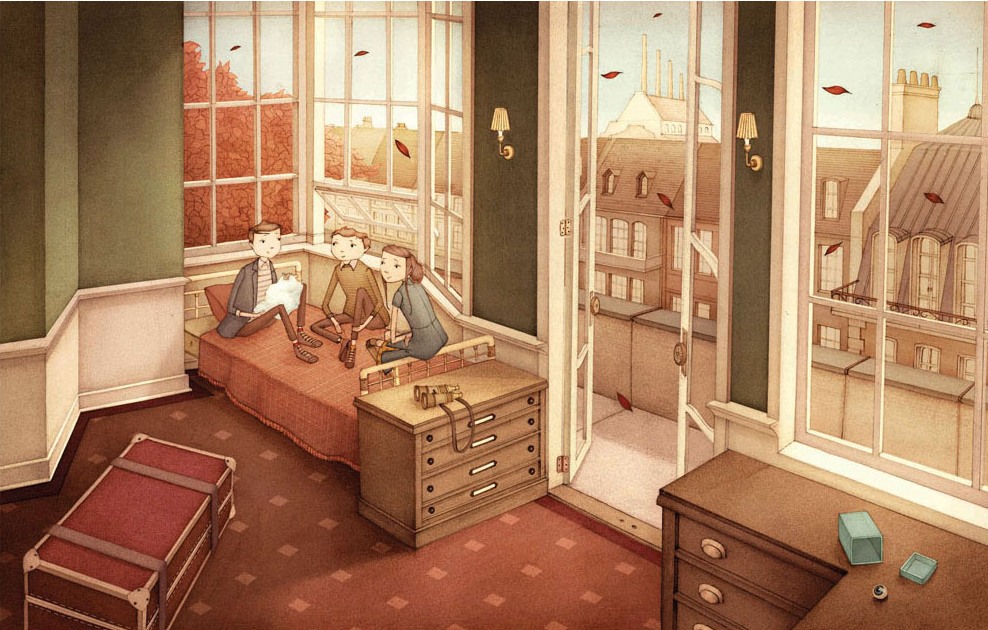

Because Archer's mother confines him to the house, and because he spends so much time alone, she doesn't notice when he occasionally slips out over the wall and across a rooftop to visit his newfound friend Oliver Glub at 377 Willow Street. Oliver's father runs the Doldrums Press, where Archer first reads about his grandparents' expedition gone awry. Oliver's mother is the opposite of Archer's. She welcomes Archer into her home and relishes any opportunity to feed and pamper him. Oliver's father, too, appreciates the "sparkle" in Archer's eyes that tells him "something was on the boil." With parents like these, Oliver has no reason to leave home. "While [Oliver] had no interest in having an adventure or anything of the sort," Gannon writes, "he was interested in having a friend, so he agreed to help Archer find his adventure if he could."

The author's formal writing style mirrors the high-society manner of Archer's mother and emphasizes the remove at which the hero finds himself. With no friends and little experience of people aside from his parents, their dinner party guests and his classmates at school, Archer has only a minimal understanding of how to relate to people. Oliver may not have friends, either, but his editor-in-chief father certainly has a broad view of society. Oliver points out the practical shortcomings of Archer's plans. For instance, when Archer brings up the idea of becoming the world's greatest deep-sea explorer, Oliver says, "What about a ship.... How can you do this without a ship?" To which Archer responds, "I'm still working it out." When the school year ends, Oliver coaches Archer to at least "talk to your mother about leaving your house this summer." That would be a first step toward adventure.

Then Adélaïde Belmont, with her wooden leg and whisperings that she lost it to a crocodile, moves into the house between Archer's and Oliver's. Archer believes he's found the perfect number three for his plan to rescue his grandparents. Surely a girl unafraid of a crocodile is ideal for a trip to Antarctica. Together the three visit the Society to which Archer's grandparents belonged, in search of necessities for their expedition. They best an Eye-Patch man, whom Archer has met before (when he dropped off his grandparents' long-abandoned trunks) and a "crooked man" who bet against his grandparents' returning ("This man made Mrs. Murkley look like a sugar plum fairy," thinks Oliver).

As the three friends make plans to escape from Willow Street and stow away on a ship bound for Antarctica, Archer and Oliver discover Adélaïde's true history, and their ideas about their plans begin to unravel: "They needed Adélaïde to be who she wasn't." But is that true? Or does the fact that she is not who they thought she was inspire Archer and Oliver to be more than they think they are?

What begins as an adventure story turns out to be, at its heart, a tale of true friendship. Each of the three breaks out of his or her own prison in unique ways so that Archer, Oliver and Adélaïde together accomplish far more than they could have on their own. --Jennifer M. Brown