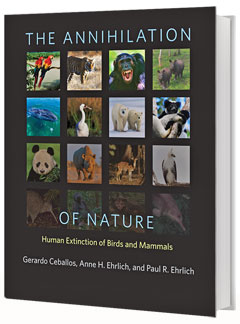

The Annihilation of Nature: Human Extinction of Birds and Mammals

by Paul R. Ehrlich, Anne H. Ehrlich, Gerardo Ceballos

Three academic scientists--Anne H. Ehrlich and Paul R. Ehrlich of Stanford University and Gerardo Ceballos of National Autonomous University of Mexico--come together in a plea to halt Earth's sixth mass extinction. The attractive, large-format The Annihilation of Nature: Human Extinction of Birds and Mammals contains original illustrations by Ding Li Yong and 83 color photographs to accompany the authors' heartfelt arguments about the value of global and regional biodiversity and the danger of extinction that currently faces so many species.

As stated in the preface, the goals of this project are to share the dire conditions with the general public, and convince that audience of the relationship between the continuing health of these diverse species and human well-being. In pursuit of these objectives, the authors have chosen to highlight mammals and birds specifically, because they are visible, sympathetic and thus likely to appeal to human compassion. The Annihilation of Nature is plainly written, well-organized and filled with arresting images.

Ceballos, Ehrlich and Ehrlich begin by describing the incredible richness of Earth's diverse forms of life, which they call a "legacy"--humanity's duty to protect and appreciate. They outline the planet's previous five waves of mass extinction and their natural causes, making the point that the present sixth event is different in that it is caused by human actions. The current time period is called by many scientists "the Anthropocene," in which "a huge and growing human population has become the principal force shaping the biosphere (the surface shell of the planet's land, oceans, and atmosphere, and the life they support)." To illustrate the interrelatedness of human actions with every natural system, basic concepts such as the food chain are reviewed. The bulk of the book is then devoted to four chapters on extinct birds, endangered birds, extinct mammals and endangered ones. A combination of illustrations and photographs brings the reader's attention to the long-gone dodo and the passenger pigeon, and species in need of conservation like the Philippine monkey-eating eagle and the New Zealand kakapo (a nocturnal flightless bird). Extinct mammals include the baiji--a freshwater dolphin endemic to China, called the "goddess of the Yangtze"--and the Tasmanian tiger, a marsupial predator with several unique physical features including striped patterning and rearward-facing pouches on individuals of both sexes. Mammals in danger today include a variety of large species: whales, big cats (lion, tiger, cheetah), bears, apes, rhinoceros and elephants, joined by the small but scrappy Tasmanian devil.

All life forms in an ecosystem are intricately interconnected. When gray wolves were reintroduced to Yellowstone National Park, their impact was profound and widespread: elk populations came under control and trees such as aspen, willow and cottonwood began to recover. The health of the willow helped beavers to rebound and beavers in turn improved riparian conditions and contributed to healthy populations of fish, waterfowl, amphibians and reptiles, as well as regulating stream flow. Songbirds have returned to the park in greater numbers with its new tree growth. Smaller predators have declined in numbers, which in turn increases numbers of small prey and then of mid-level predators like foxes and bald eagles. All these benefits came from the reintroduction of one keystone predator.

Having shared the remarkable and evocative profiles of so many creatures, the authors make their central point in chapter 8, "Why It All Matters." Here they lay out the many human-caused factors that contribute to species extinction and population extinction, including habitat destruction; chemical pollution and plastic debris; the introduction of non-native species and diseases; legal hunting and illegal poaching for meat or valued body parts such as tusks, horns and organs; and killing because of competition for food sources (the Sumatran orangutan, which vies with farmers for fruit) or because some species are seen as pests (crop-raiding Asian elephants) or predators of livestock (the gray wolf). Finally, climate change is deemed a major cause of ecological upheaval and extinction. If forced to choose a number-one factor, the authors name toxic pollutants, but climate change "may be the most threatening problem ever faced by humanity" and "climate change alone could be sufficient to finish the sixth great extinction now under way."

Finally, Ceballos, Ehrlich and Ehrlich argue that biodiversity must be valued and protected for many reasons, from the aesthetic and ethical through the services they provide to the world's ecosystems and to humans: dispersal of seeds, insect and pest control, pollination and the sanitation role of scavengers such as vultures. Keystone species are described as those with an outsized impact on their environment. In an impassioned final chapter, the authors touch on means to conserve threatened species, including the question of direct or personal action versus institutional change. They consider ethical questions, such as whether to allow limited sport hunting of African elephants to help fund their conservation, and end with a message of hope, despite the dire picture painted by most of the book. "If we could just adopt a global policy of humanely and fairly limiting the scale of the human enterprise, gradually reducing the population size of Homo sapiens, curtailing overconsumption by the rich (while increasing needed consumption by the poor), then we might leave some room for the natural systems all humanity depends on."

The Annihilation of Nature shows a deft hand with the complexities of its subject, as when wind turbines--good for the reduction of fossil fuel use--turn out to threaten insectivorous bats and the endangered California condor, or in discussing the economic inefficiency of allowing a species to die off to the brink of extinction (or even paying subsidies to kill them, as with the black-tailed prairie dog) and then spending millions to conserve the same species. This is a beautifully produced, deeply moving, powerful story that communicates what it intended to, with great emotional impact. --Julia Jenkins

Who is your target audience for this book?

Who is your target audience for this book? Presumably many endangered species of birds and mammals didn't fit into this book. How did you choose which species to discuss?

Presumably many endangered species of birds and mammals didn't fit into this book. How did you choose which species to discuss? What about animal species beyond birds and mammals, and extending into plants--what is the scope of mass extinction relative to the story told in your book?

What about animal species beyond birds and mammals, and extending into plants--what is the scope of mass extinction relative to the story told in your book?