Fairy Tales from the Brothers Grimm: A New English Version

by Philip Pullman

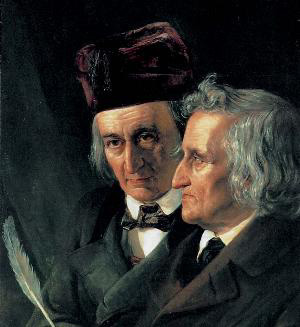

Snow White, Rapunzel, Cinderella, Rumpelstiltskin, Hansel and Gretel: they are among the most recognizable stories in the world. It wouldn't be too hyperbolic to suggest that most adults (at least in the Western world) have had a go at telling at least one of these stories to a child, whether they recite it from memory or read from some version of the tales originally compiled by Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm in the 19th century. In the two centuries since the first edition of the Kinder- und Hausmärchen (Children's and Household Tales), there have been many English-language translations and adaptations; now Philip Pullman, who helped redefine fantasy literature for the modern era with the His Dark Materials trilogy, tackles these classics with his own version of Fairy Tales from the Brothers Grimm.

Pullman takes 50 stories--"the cream" of the Grimms' inventory, and not just the obvious choices--and presents them in a way that respects the original renditions without being slavish imitations. "My main interest has always been in how the tales worked as stories," Pullman says. "How would I tell this story myself, if I'd heard it told by someone else and wanted to pass it on?" In some cases, such as "The Twelve Brothers" or "Little Brother and Little Sister," he rectifies what he calls the "clumsy storytelling" of the Grimms' sources to make the story run more smoothly.

Other revisions can be a bit more extensive. For "The Three Snake Leaves," a story in which a wicked princess conspires with a ship captain to do away with her husband, Pullman draws inspiration from two Italian variations to make the young man's death scene less ambiguous. Now, instead of simply being thrown overboard, he's strangled first. (Not to worry--the faithful servant still comes along with the magic leaves to revive him.)

Pullman's language crackles with energy, starting with the titles. Where previous editions might offer "The Story of a Youth Who Went Forth to Learn What Fear Was" or "A Fairy Tale About a Boy Who Left Home to Learn About Fear," Pullman tells us about "The Boy Who Left Home to Find Out About the Shivers." Instead of "The Worn-Out Dancing Shoes" or "The Shoes That Were Danced Through," we'll hear about "The Shoes That Were Danced to Pieces."

And the dialogue! When the enchanted fish in "The Fisherman and His Wife" introduces himself, he jumps straight into the action: "Now look, fisherman--what about letting me live, eh?" Right away, you get a sense of the comic earthiness to Pullman's characters--and since, as he notes in his introduction, the characters in Grimm's tales don't have psychological motivations or interior lives as such, dialogue becomes the chief instrument through which a storyteller can give them personality. It's a tool Pullman uses to masterful effect. Even a simple, 16-word exchange between the protagonist of "Lazy Heinz" and his equally slothful wife can reveal volumes about the characters:

"Oh, Trina, darling! If you come over here I'll kiss you."

"Maybe later," she said.

"Yeah, all right."

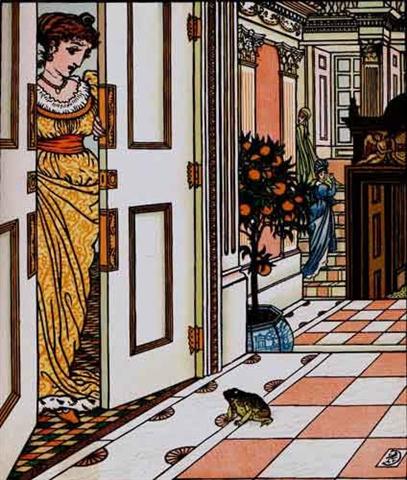

Pullman gets the utter other-ness of the worlds in which these stories take place, where young men and women are forever stumbling upon the hideouts of robbers and murderers, men fall in love with princesses at first sight and children constantly fall afoul of evil stepmothers. He also reminds us that the stories are sometimes weirder than we remember. Take the princess and the enchanted frog. She never kisses him; instead, he badgers his way into becoming her companion and invites himself into her bed, and it's only then that he transforms into the handsome prince. ("The kiss has a lot to be said for it, however," Pullman admits. "It is, after all, by now another piece of folklore itself.") And the story doesn't even end there, but goes on to introduce the prince's servant Heinrich, who had bound his heart with iron bands to keep it from breaking when his master was cursed--now that the spell is lifted, Heinrich's heart swells and breaks loose its bonds.

Each story is followed by short notes, in which Pullman identifies the Grimms' sources and lists significant variants from other folklore traditions, then adds his own personal impressions. He holds nothing back in these editorial comments: "The Juniper Tree" is a "masterpiece" he feels privileged to share, but he's disgusted by "The Girl with No Hands," sarcastically commenting, "Perhaps a great many people like stories of maiming, cruelty and sentimental piety." He has fun spinning out an allegorical meaning for one story, which turns out to be a joke: "I don't believe this interpretation for a moment," he confesses, "any more than I believe in most Jungian twaddle." And sometimes he just wonders about a loose narrative thread, as when he ponders the fate of Hansel and Gretel's stepmother. "Perhaps the father killed her," he muses. "If I were writing this tale as a novel, he would have done."

Each story is followed by short notes, in which Pullman identifies the Grimms' sources and lists significant variants from other folklore traditions, then adds his own personal impressions. He holds nothing back in these editorial comments: "The Juniper Tree" is a "masterpiece" he feels privileged to share, but he's disgusted by "The Girl with No Hands," sarcastically commenting, "Perhaps a great many people like stories of maiming, cruelty and sentimental piety." He has fun spinning out an allegorical meaning for one story, which turns out to be a joke: "I don't believe this interpretation for a moment," he confesses, "any more than I believe in most Jungian twaddle." And sometimes he just wonders about a loose narrative thread, as when he ponders the fate of Hansel and Gretel's stepmother. "Perhaps the father killed her," he muses. "If I were writing this tale as a novel, he would have done."

"When a tale is shaped so well that the line of the narrative seems to have been able to take no other path," Pullman says of one of his selections, "and to have touched every important event in making for its end, one can only bow with respect for the teller." There are several moments in Fairy Tales from the Brothers Grimm in which Pullman himself earns that honor. --Ron Hogan, founder of Beatrice.com

She began to cry, and she cried louder and louder, inconsolably. But as she wept and sobbed, someone spoke to her. "What's the matter, princess? You're crying so bitterly, you'd move a stone to pity."

She began to cry, and she cried louder and louder, inconsolably. But as she wept and sobbed, someone spoke to her. "What's the matter, princess? You're crying so bitterly, you'd move a stone to pity." Next day the princess was sitting at table with her father the king and all the people of the court, and eating off her golden plate, when something came hopping up the marble steps: plip plop, plip plop. When it reached the top it knocked at the door and called: "Princess! Youngest princess! Open the door for me!"

Next day the princess was sitting at table with her father the king and all the people of the court, and eating off her golden plate, when something came hopping up the marble steps: plip plop, plip plop. When it reached the top it knocked at the door and called: "Princess! Youngest princess! Open the door for me!" Type:

Type: