If the World Were a Village: A Book about the World's People

by David J. Smith, illus. by Shelagh Armstrong

David J. Smith's If the World Were a Village began with a question from one of his seventh-grade students. He was trying to decide between a course in French and Spanish as a foreign language: "Which one is most important?" Smith probed further to get at the root of the student's question. "Suppose our classroom represented the world, how many of us would speak English, how many would speak French, and how many would speak Spanish?" the student wondered. They went to the World Almanac to research the answer together. (The seventh-grader decided to take Spanish because it's more widely spoken than French.) This started Smith thinking: "If our world were a village of 100 people, what could we learn?"

From there, Smith and his students examined other issues at the center of society. If the World Were a Village was first published in 2002, and as it returned to press every four to six months, Smith updated the statistics, so that the global "village" continued to reflect the world's complex composition. A second edition came out in 2012, but Smith's engaging premise remains the same. By placing the population of the village at 100 people, Smith makes mathematical analysis easy.

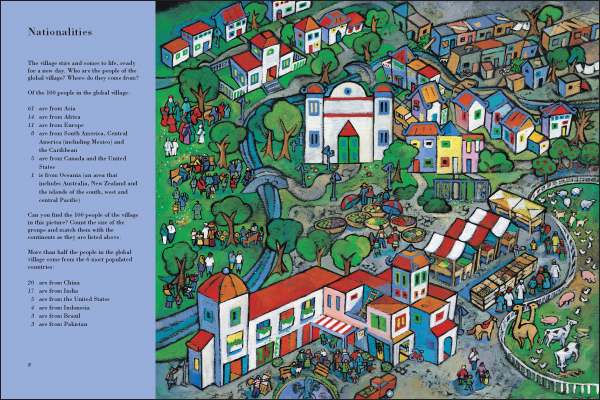

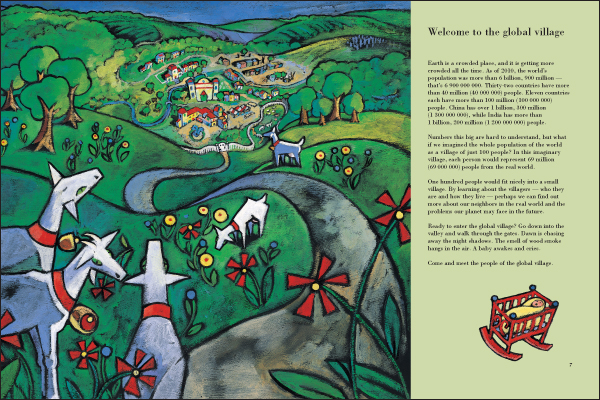

Math, geography, social studies and, ultimately, ethics come into play, simply by stating the facts. Each topic gets a two-page spread. The numbers appear in a single column, at the left or right, and the ones and 10s columns align, enabling readers to quickly add up the figures in their heads to get to a sum of 100; draw pie diagrams to represent the composition of the village; and the like. Shelagh Armstrong's paintings dominate the other two-thirds of the spread. She so delicately layers the acrylics in her paintings that they at times resemble pastels. The cover illustration immediately telegraphs the concept that this village is a symbol of a larger whole. Armstrong's opening image works in tandem with Smith's greeting, "Welcome to the Global Village." Goats stand on a hilltop looking down into the village, where readers begin, too, with a larger perspective. The artwork brilliantly conveys concrete facts in a more abstract, representative way that continues this interplay between the specifics cited in the text and the larger landscape to which Smith refers, with varying skin tones, dress and modes of transport.

As the book progresses, Smith creates an overlay of the complexity of the issues confronting the village. A standout example involves his use of the "Welcome" page, along with the spread about the "Ages" of the villagers, and a new section for the second edition called "Health." The general statistics for "Ages" remain consistent from the first edition to the second, but Smith digs more deeply into the implications of the dramatic population growth (100,000,000) from 2008 to 2010 (extrapolated from a comparison of the numbers on the "Welcome" page entries in the two editions). "At the present rate of growth, the village will increase by 12 people every 10 years. That means that the village as a whole is slowly growing larger," he writes. Smith also raises the question of what it means to support an aging population: "[M]any countries are actually getting smaller as their populations age.... A hundred years ago, there were only 8 people over 65 in the village of that time, but by 2050 there may be as many as 16." He examines this more completely in the "Health" section, where he explains that in 1850, a newborn in the village "was only expected to live to age 38." In 1900, the life expectancy was 47. Today, "a newborn can expect to live to 68, on average."

The "Food" section will likely get readers most roused. Smith tallies the number of cows, pigs, chickens and other sources of protein (including camels and horses in some societies) and discusses alternatives, such as wheat, rice and beans. By laying out the facts, Smith lets students know about the disparity of those who have "food security" and those who do not: "Although there is enough to feed the villagers, not everyone is well fed," he writes. "30 people in the village do not have a reliable source of food and are hungry some or all of the time. 17 people are severely undernourished and are always hungry." Armstrong's illustration shows a "common ground," a penned-in grassy area in the center of town, where goats, cows, sheep, pigs and chickens graze, plus market stalls with leafy vegetables, fruits and bread loaves. Horses and bicycles carry some villagers to and fro, while others walk, carrying bags and babies.

Smith also examines energy sources, "money and possessions," "school and work," along with nationalities, languages and religions. He ends with the implications of population growth: "If there are 100 people in the year 2010, there will be more than 101 in 2011, and so on." By 2150, he points out, there will be 250 people in the village. "This is an important number, because many experts think that 250 is the maximum number of people the village can sustain." He offers a message of hope: "Fortunately, groups such as the United Nations and many governments and private organizations are working hard to make sure that the village of the future is a good home for all who live in it." Yet he implicitly suggests that readers do have a role in how things turn out.

Smith also examines energy sources, "money and possessions," "school and work," along with nationalities, languages and religions. He ends with the implications of population growth: "If there are 100 people in the year 2010, there will be more than 101 in 2011, and so on." By 2150, he points out, there will be 250 people in the village. "This is an important number, because many experts think that 250 is the maximum number of people the village can sustain." He offers a message of hope: "Fortunately, groups such as the United Nations and many governments and private organizations are working hard to make sure that the village of the future is a good home for all who live in it." Yet he implicitly suggests that readers do have a role in how things turn out.

The author closes with suggestions on how to explore these topics further in conversation with young people and an exhaustive list of sources for his statistics. Smith raises questions responsibly, by using just the facts, then suggests ways to involve young people in answering their questions through further study (with tips on how adults can help). --Jennifer M. Brown

David J. Smith taught seventh grade for 26 years at the Shady Hills School, in Cambridge, Mass. He was born and raised in Cambridge and, yes, attended Shady Hills School himself from pre-K through ninth grade. After teaching in Oregon and Hawaii, he applied to teach at Shady Hills and remained there for more than a quarter century. He and his wife now live in Vancouver, Canada, and Smith travels around the world giving workshops based on If the World Were a Village, illustrated by Shelagh Armstrong (Kids Can Press). The same team has also published If America Were a Village (also Kids Can). Both books are part of the

David J. Smith taught seventh grade for 26 years at the Shady Hills School, in Cambridge, Mass. He was born and raised in Cambridge and, yes, attended Shady Hills School himself from pre-K through ninth grade. After teaching in Oregon and Hawaii, he applied to teach at Shady Hills and remained there for more than a quarter century. He and his wife now live in Vancouver, Canada, and Smith travels around the world giving workshops based on If the World Were a Village, illustrated by Shelagh Armstrong (Kids Can Press). The same team has also published If America Were a Village (also Kids Can). Both books are part of the  Over the years, what numbers have changed the most?

Over the years, what numbers have changed the most? You've recently returned from a school visit in Switzerland. What was that like?

You've recently returned from a school visit in Switzerland. What was that like?