Max the Brave is the sixth picture book that Ed Vere has both written and illustrated. It was named one of the Sunday Times's "100 Modern Children's Classics"; appeared on the longlist for the Kate Greenaway medal; and is published in 12 languages. Vere's first book, The Getaway, won the U.K.'s Highland Children's Book Award in 2007. The following year, Banana was shortlisted for the Kate Greenaway prize. Vere lives in London.

Max the Brave is the sixth picture book that Ed Vere has both written and illustrated. It was named one of the Sunday Times's "100 Modern Children's Classics"; appeared on the longlist for the Kate Greenaway medal; and is published in 12 languages. Vere's first book, The Getaway, won the U.K.'s Highland Children's Book Award in 2007. The following year, Banana was shortlisted for the Kate Greenaway prize. Vere lives in London.

Did the character of Max begin with a story, or a drawing?

Like most of my books, it started the wrong way round... with a drawing. I stubbornly prefer to start with drawing... always the principal character... and figure it out from there. It would be more logical to start with the story, but I never seem to be able to work that way round.

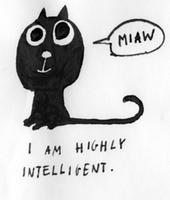

Here's an early sketch of Max.

Here's an early sketch of Max.

I initially thought that he might be highly intelligent, belying his appearance. In another sketch of him and the Monster, I wasn't quite sure what would happen between them, but there was a good dynamic and a feeling of impending doom.

How did the story develop? We loved that Max gets more freedom than a human toddler would, yet he shares many of the same instinctive curiosities and questions. Is Max based on anyone you know?

My stories always develop in fits and starts. I get a sense of who the character is by drawing and redrawing them in lots of different situations. I put words in their mouths and see if they feel right. When I've got a good feel for them, I can pare it back and concentrate on the narrative arc. But I know they'll be strong enough to stand up on their own.

I guess Max is really a toddler in another form, with a toddler's insatiable curiosity about life. He likes to explore and doesn't take much for granted. In that way, he's also a bit like me.

How do you approach your artwork? Do you begin with drawings and move to paint? Do you start with pen and inks? Your illustrations are so loose. How do you keep that spontaneous quality?

I usually begin with the same pen I'll use to draw the book. I use a ruling pen. The dial on the side is for adjusting the width for when you're ruling lines. I normally have it set fairly fine and then use the side of the pen if I want a broader stroke. It's a dip pen, so I dip it in a pot of ink. It's used for ruling lines, by architects and surveyors. It's got a wonderful variety of line. I've been using it for years now. It was a gift from a friend; it used to belong to his uncle, an architect, but dip pens have been replaced by computers now.

The pen-and-ink drawings are scanned into Photoshop, where I compose the image and play with color and texture. I love spontaneity and try to keep the drawing as fresh as possible. I rarely rough out a drawing. Instead, I draw out again and again from scratch to get the right expression. I always think drawing's a form of acting--you have to sort of act out the expression you're after as you're drawing it. I can spend days on one drawing, over and over, not getting it right. It's maddening, and then magically, you get into a zone where it flows, you're understanding the character, how they act and how they express themselves.

We loved the pacing of Max's adventure. For instance, you go from the four introductory images of Max rather small on the page to the full-page portrait of Max as the "fearless kitten," the "brave kitten." Do you do thumbnail sketches? Do you tack your sketches to the wall?

I make all the drawings fairly small. At that stage I haven't thought about the layout but more about getting the expression right for that moment in the story. I then scan and compose in Photoshop. At that point, I start to consider the pacing of the drawing in the layout and how it plays out throughout the story. Varying the size of certain drawings lets me place emphasis at important moments. It's definitely a kind of fumbling in the dark process all the way along, and hopefully that's what keeps it spontaneous. If I spend too much time roughing it out, I lose the freshness and sense of immediacy.

Two of my favorite "cause-and-effect" illustrations are when Max asks Fish if he's Mouse (first looking from afar, then physically attempting to enter the fish bowl) and when Max, on the ground, asks the birds high up in a tree if they are Mouse, and the next image depicts the birds on the ground with Max on their previous perch. Can you talk about the use of time-lapse in these?

Haha. I'm glad you like those. I do, too. I was trying to suggest Max's primal instincts, even if he doesn't quite realize it himself yet. He's being terribly polite all the way along. Yet essentially, somewhere deep down, he knows that they're potentially lunch... and so do they.

I think that sense of two-stage animation tells you a lot about Max's character--or the hidden aspects of it. Maybe there's a Freudian undertone to it. It was initially a three-part sequence. I liked the fact that Max's primal instincts were being foiled in such a simple way.

The beauty of picture books, an almost unique aspect, is that you have two things working alongside each other, words and pictures. There's no point only illustrating the words. You can suggest different qualities with each. You can make them diverge to create questions in the reader's mind. There's a gap of understanding that you don't need to explain, which then requires the imagination. And once that starts happening, the character, Max, is living in someone else's mind, too. They start to create their own narratives and get their own ideas about what might happen.

Your visual build-up to the Mouse (aka Monster) is so wonderfully dramatic. How did you pace your illustrations to create that impact at the page turn?

Your visual build-up to the Mouse (aka Monster) is so wonderfully dramatic. How did you pace your illustrations to create that impact at the page turn?

The page turn is another aspect to picture books which is quite unique. It rarely matters in a novel where a page turn occurs in the text, but in a picture book, it's vital. That's the point where you create anticipation--a small cliffhanger, egging you on to find out what's going to happen. I started the sequence by increasing the size of the animals and reducing their domestic status, but then broke the rule with the rabbit. Rules are there to be broken; it shouldn't be too obvious.

Tell us about how you focus on the eyes of each character (especially Max) to convey emotion.

When I first drew Max he had a mouth, as in this drawing of him asleep. But I wanted him to be as graphically simple as possible, so all the expression had to come from the eyes and gesture. It was a challenge to see if I could do that, and sometimes a limitation allows more to happen. All my characters seem to have expressive eyes.

It's one of the things I love about drawing that's hard to explain--you're acting with the pen, and every gesture when drawing the eyes suggests something entirely different. Quentin Blake is a genius in that respect. Quite often he limits himself to just using dots for the eyes, but the placement of the dot and the expression they're able to convey is incredible.

It's one of the things I love about drawing that's hard to explain--you're acting with the pen, and every gesture when drawing the eyes suggests something entirely different. Quentin Blake is a genius in that respect. Quite often he limits himself to just using dots for the eyes, but the placement of the dot and the expression they're able to convey is incredible.

How involved are you in the design of your books? The choice of background colors (green for the pink elephant; turquoise to orange to tomato red backgrounds for the monster), was that yours?

I'm very involved. I initially design myself and then have conversations with my designer about what does and doesn't work. I then go off and think about it and act on what we've talked about. It's always good to have somebody else's eyes on it, a bit of distance. I'm lucky to work with a great designer, Goldy Broad, who doesn't impose too much on what I want to do. She's got good instincts, which, for the most part, I trust. But she'd be the first person to tell you I'm very stubborn sometimes (maybe, most of the time).

Is there another Max book in the works?

Not just one! I've already finished book two, Max at Night, which is a bedtime story--almost a lullaby, but with Max's hallmark curiosity. Max is very tired. It's WAY past his bedtime. But before he goes to bed he absolutely must say "Goodnight" to the moon, as you do... but where is the moon? Nighttime adventures ensue.

I'm just finishing the third book at the moment, Max and Bird, in which Max attempts to make friends with Bird. However, Bird isn't in total agreement that being chased and eaten are the best aspects of friendship... so a compromise (including flying lessons for Bird) has to be struck. Will Bird end up as a tasty snack? Hmmm. --Jennifer M. Brown