.JPG)

|

|

| photo: Rob Casey | |

Sherman Alexie is a poet, short story writer, novelist, filmmaker, performer, and winner of the National Book Award for Young People's Literature for The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian. A Spokane/Coeur d'Alene Indian, Alexie grew up in Wellpinit, Wash., on the Spokane Indian Reservation and now lives in Seattle with his family. Here, he talks with Shelf Awareness about personal identity, carnivorous spirit animals and his debut picture book, Thunder Boy Jr. (Little, Brown, May 10, 2016), illustrated by Yuyi Morales.

So, my most pressing question is: Have you ever in your life worn yellow overalls like the ones Thunder Boy wears?

Oh my gosh! You know, we grew up on the rez poor. We weren't exactly an OshKosh B'Gosh family. So, if I did wear overalls, I'm pretty positive they would have been Wrangler, in a standard blue.

Identity is a major theme for you personally--it makes sense that your first picture book would be about identity, too.

But it's not a kid insecure about his Native identity. It's a kid insecure about his existential meaning in the world. It's also about your self-definition, and that's the most important thing. A tribal identity is one thing. It's beautiful, or it can be beautiful. But personal identity is so eccentric. True Diary is about a painful dysfunctional march toward identity, Thunder Boy is about a loving, beautiful journey toward that same thing. I don't think we often think in the popular culture or the literary culture about the Native American quest for identity being beautiful.

|

|

Where did the idea for Thunder Boy Jr. come from?

Two origins really. I was at my father's funeral in 2003 and they lowered the casket and I looked at the tombstone and it said "Sherman Alexie." I'm Sherman Alexie Jr. So, I thought, oh my god, the weight of being a "junior" at that moment was intense. I knew I'd have to write about it in some way.

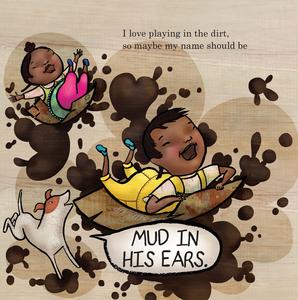

And then the other thing is that it was a family game we played our entire lives, of giving each other Indian names, based on the moment. Sometimes loving, sometimes teasing. And I've continued that tradition with my kids. So, it's a way of playing around in an everyday fashion with an ancient tradition.

What is that tradition?

It's an adulthood ceremony. A kid would get a new name based on something they'd accomplished. For instance, Crazy Horse's first name was Curly. And then at some point, because of various accomplishments, he became Crazy Horse.

Curly?

Curly. It sounds funny because of the cultural context of the Three Stooges, but the Three Stooges didn't exist when they called Crazy Horse Curly.

I guess the movie Dances with Wolves went a long way to broadcast this tradition?

Yeah, it did. In good and bad ways. Understanding and empathy for Native American culture, yes, but also lots of appropriation of white people giving themselves Indian names. Lots of vegetarian white people giving themselves the names of carnivorous spirit animals. Nothing's funnier than a vegan telling me their spirit animal is something carnivorous like an eagle.

|

|

Where did the name Sherman come from? I know it was your dad's name, but...

Well, one of things that happens in the Native world is that there's still this desire to give your kids really ornate names, really poetic names. If you don't call your kid Crazy Horse, you're going to call your kid something fancy, in the contemporary idiom. I've got a cousin named Aristotle, my dad's dad's name was Adolf and his dad's name was Alphonse.

Did you have a nickname?

Junior. My father also had a nickname for me based on a Western character... a character named Regret. Did that not doom me to a life of writing? This is Regret, and here's my sister Ennui.

Did you have a close relationship with your father like the boy in the book?

No. Not nearly as beautiful. That was also part of the book, to represent that overtly tender, overtly loving relationship. I never doubted my father's love, but he was a mess. To show a non-mess Native father and non-mess Native mother as a family unit was important to me.

How did it go for you, writing a picture book?

Well, because I'm a poet, I thought it would be easier. I'm used to writing things that have 50 words and have to carry the meaning of the world in them. But that wasn't the case here. It wasn't even like poetry for kids, which I've also done. There's this magic point where the book becomes 70% for the kid and 30% for the adult who reads the book to the kid. And you have to find that percentage, and it took a long time.

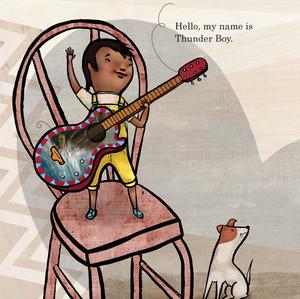

The artwork in Thunder Boy Jr. could not be more exuberant. Did you collaborate with the illustrator, Yuyi Morales?

No, she read the book and went for it, so that's her. In some ways I feel like I was the screenwriter and she was the cinematographer. One of the reasons I picked her, among many, was that she's a she. And she's a mother. And, because she's Mexican and is very familiar with indigenous culture. And also, she's a minority in the United States. So I think her artistic ambitions and mine, politically speaking, matched up well. So when I first saw the drawings I thought, "Ahhhh, yes, yes, yes."

What I had imagined was this Salish kid from Washington State. From Seattle. I imagined him as a contemporary, indigenous person, which means his cultural influences are vast... from different places. Thunder Boy has a very specific personal identity, but the artwork has influences from many parts of the country, from Mexico's and Central and South America's indigenous imagery. We wanted to speak to a wide variety of people inside of indigenous communities.

|

|

Thunder Boy says, "I once touched a wild orca on the nose, so maybe my name should be NOT AFRAID OF TEN THOUSAND TEETH." In that scene, Thunder Boy's dad is wearing an orca mask. Is that what you had in mind?

I meant it as a metaphor, not real. I meant it as a kid dreaming. But Yuyi and I never talked about it. So, when I saw that as his father, oh, that made me cry. It's gorgeous and, no, that was her. That was one of the most beautiful things about this--Yuyi and I collaborated, but at a distance. And I completely trusted and respected her vision.

Do you have more books for young people in the pipeline?

The sequel to True Diary that I've been working on for years, and there are a couple of picture book ideas brewing again. My picture book here deals with very serious issues... and that's what I'm aiming for. That strangest of creations, the politically, socially charged picture book. And I want to do the Native versions of them. I'm not interested in talking animals. I'm not interested in telling the story of Running Bear. I'm interested in how Native kids live now. --Karin Snelson, children's & YA editor, Shelf Awareness