The Way Things Work and The New Way Things Work are classics. What inspired this 2016 revision?

The Way Things Work has remained popular since its publication in 1988, but it's been 18 years since the last edition. Technology, as you may have noticed, has been racing along. It's still a book about the basic principles of physics and how they link different machines, even when those machines perform a surprising variety of functions. To keep it relevant for a new generation, especially alongside the Internet, the book needed to include some more recent devices. Linking those same principles to machines we not only take for granted but that we've become addicted to seems to be an essential responsibility of TWTW, not to mention a great opportunity.

What's the same about this new edition?

The basic premise that guided the original book remains intact. It's the book's job to provide just enough reliable information in an engaging way to satisfy the basic appetite of any reader, while encouraging curiosity and with it, further exploration. Thanks to the Internet, more information is available more quickly than ever, but this doesn't equate to understanding, in fact, perhaps the opposite. It's easy to become overwhelmed by it all. But a book, even a 400-page book, has a very real and perhaps reassuring end. There will always be more to know than any book can contain.

And what's new?

And what's new?

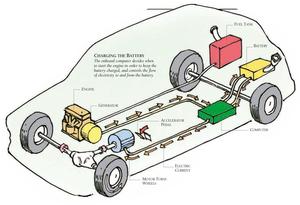

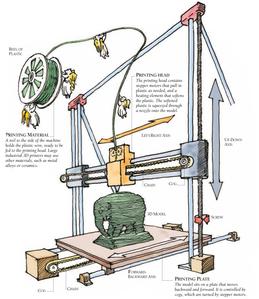

Approximately 50 pages of new material. As with the original edition, it took a small team of researchers, editors and designers to make the necessary changes without destroying what made the book work in the first place. We talked about the sorts of gadgets we use in our lives today, and compared that list with what was in the 1998 edition. Some things, like the digital camera, are simply digital versions of existing technologies. But some--for example, 3D printers--have only become commonplace in the past few years. We did somehow overlook the hybrid auto until a friend asked me about it, assuming it would be there. Thanks to him, it is.

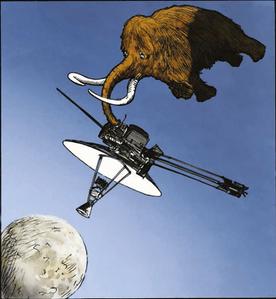

How did so many mammoths wander into a book about technology?

Taking on a 400-page book was a first for me, but taking on a 400-page book about machines was doubly daunting. It wasn't just the scale of the project that made me nervous, but my inability to see how I was ever going to be able to play with the material. The mammoth changed all that.

For weeks I sketched gears and wheels, levers and pulleys, desperately looking for some reassurance in the fun department. One afternoon, running on empty, it occurred to me that cave people probably used at least a few simple machines. I have no idea where the thought came from, but I went with it and sketched a few of them standing around a log and a rock. Apparently they were thinking. After setting the log on top of the rock, they had created an early seesaw--perhaps the first one. Then I scribbled some trees in the background and among them a sketchy mammoth. Why not? The next thing I knew, the mammoth was on one end of the seesaw and the "villagers" were on the other. For some reason they had decided to weigh the poor creature and in the process had created a simple scale. The questions began to flow, and one thing quickly led to another. How did the cave people get the mammoth to sit on the end of the lever? Can you tame a mammoth? Supposing the mammoth isn't a willing participant? Swamp grass and a ramp joined the log and rock and I was on my way. And that's where the mammoths came from. No ingenious corporate plan. No focus group. Just a little desperation and a mind slightly off the rails.

For weeks I sketched gears and wheels, levers and pulleys, desperately looking for some reassurance in the fun department. One afternoon, running on empty, it occurred to me that cave people probably used at least a few simple machines. I have no idea where the thought came from, but I went with it and sketched a few of them standing around a log and a rock. Apparently they were thinking. After setting the log on top of the rock, they had created an early seesaw--perhaps the first one. Then I scribbled some trees in the background and among them a sketchy mammoth. Why not? The next thing I knew, the mammoth was on one end of the seesaw and the "villagers" were on the other. For some reason they had decided to weigh the poor creature and in the process had created a simple scale. The questions began to flow, and one thing quickly led to another. How did the cave people get the mammoth to sit on the end of the lever? Can you tame a mammoth? Supposing the mammoth isn't a willing participant? Swamp grass and a ramp joined the log and rock and I was on my way. And that's where the mammoths came from. No ingenious corporate plan. No focus group. Just a little desperation and a mind slightly off the rails.

What are some of the biggest changes in the world since TWTW came out in 1988?

What are some of the biggest changes in the world since TWTW came out in 1988?

The main change is definitely the rise of digital technology. We still do the same kinds of things--record images, sounds and video, watch TV and communicate--but these things are now nearly exclusively done in the form of binary digits. The other main ones, also digital, are the Internet and the rise of mobile devices--in particular, the smartphone.

When I laid out the first sample pages back in 1986, maybe a little earlier, I created the text with my first computer, that little "Mac in a box," and a dot matrix printer. Both appeared in the first edition.

Your books appeal to a wide age range. Where does your gift for explaining how things work come from?

I've been a teacher most of my book-making life, which means I've also been a student all that time. I've never had all the answers, but I love asking questions. For me, developing worthy content has everything to do with figuring out what the best questions are. I want at least a sense of story in my books, even if it's a little on the thin side or perhaps purely whimsical. I guess I assume people read my books not just for the accurate information, but for my ability to decide what to include, what to leave behind, and how to present it. I am not unique in this, but I do seem to have a talent for choosing and then showing how things work that reveals my own enthusiasm for and enjoyment of discovery. If I've been true to my own interests, that enthusiasm will probably be somewhat contagious... and not just for any one age group.

You've worked on a broad range of projects in the course of your literary career.

You've worked on a broad range of projects in the course of your literary career.

I'm proud of all my books because I put everything I can into them--which explains why, after the first five or six books, I almost never met a deadline. But my favorite books are the ones that have lured me into the unfamiliar, and then encouraged me to determine the best ways of presenting what I have learned. Underground comes to mind. There wasn't an earlier version of "underground" on the shelf to help guide me. I started with a blank slate and relied on my enthusiasm and common sense and asked every question I could think of, of every person with direct knowledge of what goes on down there.

My all-time nostalgic favorite has to be Cathedral, my first book. I had no idea what I was doing and no pattern to follow. It was incredibly liberating. Sadly, you only get one chance to work in such blissful ignorance, unless of course you're happy to just repeat yourself. Otherwise you're always looking over your shoulder and wondering whether or not the new project will be good enough. You become your own worst competition.

How many mammoths can dance on the head of a pin?

Generally, between six and 14, but this is seasonal and often site-specific. --Jaclyn Fulwood