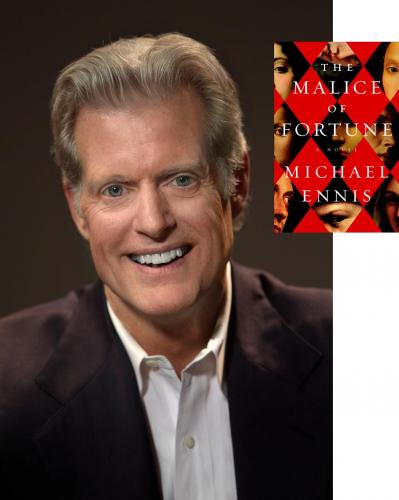

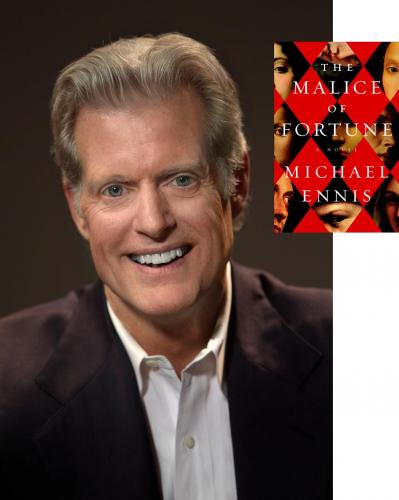

Michael Ennis earned his degree in history at the University of California, Berkeley, taught art history at the University of Texas, Austin, and developed museum programs as a Rockefeller Foundation Fellow. He is the author of two previous historical novels, Duchess of Milan and Byzantium. He has written for Esquire and Architectural Digest, and is a regular contributor to Texas Monthly. He lives in Dallas with his video producer wife, Ellen, their daughter, Arielle, and their Australian shepherd, Zoe.

Michael Ennis earned his degree in history at the University of California, Berkeley, taught art history at the University of Texas, Austin, and developed museum programs as a Rockefeller Foundation Fellow. He is the author of two previous historical novels, Duchess of Milan and Byzantium. He has written for Esquire and Architectural Digest, and is a regular contributor to Texas Monthly. He lives in Dallas with his video producer wife, Ellen, their daughter, Arielle, and their Australian shepherd, Zoe.

A series of gruesome murders play out against a backdrop of court intrigue and dark magic in his latest novel The Malice of Fortune (Doubleday), reviewed below. Teaming up to solve the mystery are none other than Niccolò Machiavelli, Leonardo Da Vinci and a beautiful courtesan with a mysterious past.

The historic events you chose are rich with possibilities for fiction storylines. How did these events inspire you as the backdrop for a mystery?

This convergence of well-known personalities and political turmoil--events that became central to Machiavelli's The Prince--would alone seem to be more than a full plate. Yet I decided to interweave this political drama with a murder mystery that involves the unmasking of a serial killer, because the murder mystery--or more properly the mystery behind a series of historically documented murders that began with the assassination of the Borgia Pope's cherished son in 1497--was not only integral to the power struggle that unfolded in the final months of 1502, but also illuminated that political drama and its far-reaching consequences in a way that documented history simply could not.

I started with the known facts: Leonardo da Vinci and Niccolò Machiavelli were both at the court of Cesare Borgia in the obscure little Italian city of Imola at the end of 1502, a meeting of the minds that in many ways jump-started the modern world. And we have ample evidence that in Imola both Leonardo and Machiavelli became intimately--and terrifyingly--familiar with an individual whom today we would describe as a psychopathic serial killer. So the task I set for myself was to take the documented history and the questions it raised, and infer from them an entirely plausible "undocumented history"--a dramatic narrative that would that answer questions about Leonardo, Machiavelli and The Prince that the historical record certainly raises, but has never answered. As Machiavelli says in introducing his own narrative at the beginning of The Malice of Fortune, there is a "terrifying secret I deliberately buried between the lines of The Prince." That secret--a murderer's secret--is no fictional invention, and it is impossible to fully understand The Prince, which continues to have a transforming effect on Western culture, without deciphering it.

This may be the first time in fiction that Machiavelli has been portrayed as a heroic, even sexy protagonist. What was your motivation in making Machiavelli and The Prince the centerpiece of this novel?

This may be the first time in fiction that Machiavelli has been portrayed as a heroic, even sexy protagonist. What was your motivation in making Machiavelli and The Prince the centerpiece of this novel?

Machiavelli has a great saying that I cite: "Everyone sees what you appear to be, few truly know what you are--and those few dare not oppose the opinion of the many." He was referring to how easy it is to acquire a good reputation if you simply keep up appearances. But his own case proves the flip side of this axiom--it is also very difficult to dispel a bad reputation, once "what you appear to be" becomes enshrined in popular opinion. And for centuries Western culture has imputed to Machiavelli's personal character the most extreme and often poorly understood values of The Prince. His name has been transformed into an adjective that remains widely used today, but his enduring notoriety has given him an undeserved reputation as a self-help guru for amoral, ruthlessly self-interested connivers of all sorts, from ambitious corporate executives to mass-murdering dictators.

The truth is, if you get into the details of Machiavelli's life and read his extensive personal correspondence, a very clear picture emerges of a man who could not have been less "Machiavellian." A loyal, charismatically charming friend and scrupulously honest public servant, Machiavelli struggled his entire life to empower people rather than princes--not to mention being an incurable romantic who often professed, in ornate prose and poetry, his belief that love conquers all. So as a fictional character, history's real Machiavelli has the ability to shock, simply because he isn't at all what our popular notion of "Machiavellian" has told us to expect.

You've proposed a different way of reading The Prince than is traditionally taught in the classroom--as a study of human nature rather than a ruthless how-to guide to power. What lessons do you think we can still draw from it in the 21st century?

The Prince is the key to the widespread mischaracterization of Machiavelli himself, because in it he seems to advise self-aggrandizing despots on the most effective ways to grasp and hold on to power--we believe that's all there is to his political philosophy because The Prince is usually taught out of context. I would suggest that it is actually harmful to teach The Prince without also requiring a reading of Machiavelli's uninvitingly titled Discourses on the First Decade of Titus Livy, a more complete work that lays out Machiavelli's true political beliefs. In the Discourses, Machiavelli details his preference for the superior if imperfect wisdom of the people, as he passionately advocates representative government--a radical egalitarianism that would not become a potent political force until the American and French revolutions more than 250 years later. The Prince was merely Machiavelli's plan B, an instruction manual for the Medici prince who took over following the complete collapse of the Florentine republic, amid a an imminent threat of foreign invasion. In this context, Machiavelli intends The Prince to be consulted only when political prudence has long been disregarded, chaos reigns and the only choice, if a people are to avoid enslavement by foreign powers, is between effective or ineffective despotism. But the Discourse's lucid, carefully laid out case for moderation, openness and fairness was so far ahead of its time that today it could not be more timely for the Western governments and economies that are presently perched on the edge of a precipice.

Instead we've got a lot of false Machiavellians--both in business and government--cluelessly thumbing through The Prince, either literally or metaphorically, and their reckless self-interest is bringing down the whole system of free-market democracy that they imagine they are advancing. Today we hear from our leaders of all political stripes that we can no longer afford to be good--we must separate the world into winners and losers, and make sure we end up among the winners, regardless of how we get there. But what Machiavelli really says is that if we want to preserve the institutions by which we profit and remain free, we can't afford not to be good.

In a book about the victimization of women, Damiata--a beautiful courtesan driven by the desire to protect her son--provides a counterbalance of feminine strength. We also see a human side to Machiavelli through his love for her, so that in a sense, Damiata seems like the emotional center of the novel.

You've really hit the nail on the head here, because the biggest problem I confronted with the entire narrative was how to get readers emotionally invested in a central protagonist--Machiavelli--whom they are predisposed to see as one of history's most toxic, evil personalities, and a bit of an anti-feminist at that. So in that sense, everything must begin with Damiata: only when we have discovered Machiavelli just as she does in her "real-time" narrative, and come to believe as she does in his essential virtue and humanity, can we make an emotional investment in him and his story as he subsequently tells it. And even then, Damiata's wrenching personal quest to free her son, in concert with Machiavelli's quest to save her, provides the emotional drive for Machiavelli's own narrative. It's an interesting dependence, because it mirrors Machiavelli's real life. My research revealed a man who relied throughout his life on strong, independent women for his own emotional and intellectual support. His mother was an educated woman who was the widow of a prominent "pro-democracy" Medici opponent when she married Bernardo Machiavelli, and I believe that she more than Machiavelli's legalistic, cautious father was responsible for his egalitarian beliefs. And throughout his life Machiavelli sought out the companionship of women much like Damiata, educated courtesans whose real trade was intellectual engagement--far more than merely physical--with powerful men. Machiavelli, who never escaped Florence's beleaguered middle class (which was much like America's today), certainly couldn't afford these ladies' professional services, so these were real friendships.

How did you come up with the puzzles and diagrams that are the focus of the mystery?

Here again history presented everything. Leonardo da Vinci's Map of Imola, which is the basis for the murderer's elaborate game-playing, is one of his lesser-known but most revolutionary works--an exactly scaled "aerial" perspective that anticipates by centuries the kind of satellite views we now get in Google Maps. This remarkable map, which Leonardo completed about a month before my story begins, still exists; it's now in Windsor Palace's Royal Library. The murderer's geometric overlay, derived from Archimedes' proofs, is based on an actual note that Leonardo wrote in the summer of 1502, just months before the events I describe, saying that he expects to get a text of Archimedes' theories from Vitellozzo Vitelli, one of the prime murder suspects. So these historical details could be worked neatly and quite plausibly into the plot.

In this novel, the city of Capua is synonymous with unspeakable horrors committed against innocents, mostly women. Does this have a basis in historical fact?

Like all the other details, this massacre is presented in The Malice of Fortune exactly as it is recorded in history--all of the suspects in the murders were actually present there, and the horrors they and their soldiers inflicted on the innocent townspeople, which I chose to keep mostly "offstage" and allusive, are so barbaric that they would probably be taken as over-the-top inventions if I had explicitly spelled them out. Executed by a massive mercenary army, the sack of Capua exposed the brutal corruption of the condottieri, the cabal of warlords who profited--extravagantly--from Renaissance Italy's privatized warfare. Machiavelli, by the way, considered these preening private warlords the greatest evil of his time, as morally bankrupt as they were militarily ineffective, whenever they were called upon to defend Italy from actual foreign invaders. The condottieri went from war to war--most of which they instigated for business reasons--unscathed, becoming the wealthiest men in Italy while the little people whose cities were sacked and fields plucked clean paid with their lives and livelihoods for the whole egregious system. And if anyone wants to see the condottieri as a metaphor for today's financial industry, be my guest.

Of Da Vinci's drawings of the human body, Damiata says, "The Maestro has found this secret world beneath our skin." In your depiction of Renaissance Italy, secret worlds abound--in the esoteric sciences practiced by Da Vinci, in the witch covens of the Italian countryside, in the private bedchambers of princes. Do you see Renaissance Italy as a setting with particular potential for the mysterious and the unexplained?

What makes Renaissance Italy such an effective setting for this sort of thing is the very evident tension between the dawn of modern scientific empiricism and the persistence of ancient superstition. In fact, it's often hard to draw the line where the infant sciences become distinct from arcane practices like alchemy and astrology. And often what appears cryptic and mysterious, such as Leonardo's drawings of veins and arteries--the "secret world beneath our skins"--becomes the basis for a conceptual breakthrough like Leonardo's precocious understanding of how a system of valves and a powerful pump--the heart--forces blood to circulate throughout the body. So I think the real interest is not just all this arcana per se, but the often quirky dialogue between the emerging modern mind and a world still dominated by magic, demons and deities. That was something I made a real effort to capture, rather than to portray Leonardo and Machiavelli as preternaturally prophetic and clear-headed in their thinking. Like all true innovators, they must struggle against the immense weight of established beliefs.

Witches and witchcraft are integral to the story. How much of this was based on fact? Did you take liberties in order to weave some magic into this otherwise historical tale?

Here again, I didn't need to invent anything. Instead I did enough research for a stand-alone historical novel simply to find the authentic details that would really bring to life a single episode--though it is an episode that ripples throughout the entire book.

In Renaissance Italy the pervasive influence of stregoneria--the ancient folk religion, based on the cult of Diana, practiced by streghe, or witches--is attested by the brutal efforts of the Church to suppress it, as well as the survival of the stregoneria into at least the early 20th century. Most of the witchcraft details in The Malice of Fortune were taken from transcripts of trials conducted by the Inquisition in the exact area of the Romagna where my account takes place. The use of a Latin textbook as a bogus "book of spells," which figures so prominently in the plot, is one such detail, along with all the incantations and physical elements involved in a Gevol int la caraffa--a divination wherein the Devil is summoned to appear in a jar of water. The use of a narcotic ointment to bring about a hallucinatory "night ride" is described in a number of Renaissance-era sources, along with fairly specific recipes for mixing this concoction. But as much as I strove for verisimilitude, part of that realism was preserving an authentic sense of "magic" and wonder surrounding these rituals, because whatever credence--or lack thereof--we might attach to them, the streghe were true believers in the services they performed, at great risk, for impoverished communities that were only victimized by both the Church and state. --Ilana Teitelbaum, book reviewer at the Huffington Post

Michael Ennis: Rethinking Machiavelli

Many years ago, an uncle gave me a copy of The Hobbit, which I read with great pleasure (and still have). It's a literary rite of passage. Today, September 21, marks the 75th anniversary of the publication of The Hobbit, and tomorrow is Bilbo Baggins's birthday, traditionally celebrated by Tolkien fans as "Hobbit Day." Tolkien's publisher, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, has sent out more than 1,000 event kits--with balloons, trivia questions, movie posters, etc.--to bookstores, teachers, homeschoolers and librarians to encourage participation; more information is at Read the Hobbit.

Many years ago, an uncle gave me a copy of The Hobbit, which I read with great pleasure (and still have). It's a literary rite of passage. Today, September 21, marks the 75th anniversary of the publication of The Hobbit, and tomorrow is Bilbo Baggins's birthday, traditionally celebrated by Tolkien fans as "Hobbit Day." Tolkien's publisher, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, has sent out more than 1,000 event kits--with balloons, trivia questions, movie posters, etc.--to bookstores, teachers, homeschoolers and librarians to encourage participation; more information is at Read the Hobbit.

Michael Ennis

Michael Ennis This may be the first time in fiction that Machiavelli has been portrayed as a heroic, even sexy protagonist. What was your motivation in making Machiavelli and The Prince the centerpiece of this novel?

This may be the first time in fiction that Machiavelli has been portrayed as a heroic, even sexy protagonist. What was your motivation in making Machiavelli and The Prince the centerpiece of this novel?

When She Woke by Hillary Jordan (Algonquin, $14.95)

When She Woke by Hillary Jordan (Algonquin, $14.95)