B.A Shapiro is the author of The Art Forger, a literary thriller about the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum heist that spans three centuries of forgers, art thieves and obsessive collectors. Writing as Barbara Shapiro, she is also the author of five suspense novels The Safe Room, Blind Spot, See No Evil, Blameless and Shattered Echoes, as well as the nonfiction The Big Squeeze. She lives in Boston with her husband, Dan, and dog, Sagan, and teaches creative writing at Northeastern University.

B.A Shapiro is the author of The Art Forger, a literary thriller about the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum heist that spans three centuries of forgers, art thieves and obsessive collectors. Writing as Barbara Shapiro, she is also the author of five suspense novels The Safe Room, Blind Spot, See No Evil, Blameless and Shattered Echoes, as well as the nonfiction The Big Squeeze. She lives in Boston with her husband, Dan, and dog, Sagan, and teaches creative writing at Northeastern University.

How did you begin your writing career?

I was in my late 30s and had a big, 60-hour-a-week job, along with a three-year-old and a six-month-old. I decided I didn't want to live like a crazy person, but knew I wouldn't be happy as a full-time mom. At that time, in the '80s, women were going to "have it all," and it was a kind of capitulation to quit work. But I did it and, not surprisingly, found myself wondering if I wasn't "superwoman," who was I?

One day I was having lunch with my mother at the Museum of Fine Arts here in Boston, freaking out about what I should do with my life. She asked, "If you had one year to live, what would you do?" I said, "Write a novel and spend more time with my children." So I decided that's what I'd do.

Fortunately, my husband was cool with this and we agreed that I would take a couple of years to write, and then he'd take a couple of years to write and I'd go back to work. Since then I have written 10 novels (not all published), and the poor guy is still working. I always tell my students that you need a working spouse with benefits to be a writer.

I'd dreamed of being a novelist since I was a little girl. But since I was going to be superwoman--wife, mother, professional--writing had never seemed a practical option. I had no training as a writer--my degrees are all in sociology--but I'm a voracious reader (my best advice for learning to write is to read) so figured if it was good enough for my last year of life, I might as well give it a try.

So I sat down and wrote a novel. I had no idea what I was doing. When I was done, I found an agent. The book didn't get published, so after I cried a few tears, I took all the rejection letters and read them. Painful as this experience was, it became clear to me that the letters all said, each in their own way, I needed more "story." I took a bunch of adult education classes, met some other struggling writers, and four of us started a novel-writing group. We studied together, talked, and we taught each other. Two of us have been together 25 years, and three of us have been published. Pretty incredible. I later started teaching adult education classes on writing, ran a business giving novel-writing seminars, and now I teach writing part-time at Northeastern University

Your descriptions of art and creating art ring true. Do you have an art background?

No. But I interviewed a lot of artists, gallery owners and collectors, read dozens of books, scoured the Internet and spent endless hours at museums. I have always loved art; I wish I had artistic talent, but I don't. So this was the next best thing: to create a character who was a really good artist and live vicariously through her.

After I was finished I gave it to a number of artists to read, and they were all amazed at how well a non-artist could write about the process. Maybe because writing isn't all that different. But my favorite story came from Craig Popelars (at Algonquin Books) who gave an early copy to a bookseller to read. She gave it to her elderly father who was in the early stages of dementia. As a young man, he had given up art. He read the book in a day, then for the first time in decades he started to paint. What more validation could I want?

How about the art forgery details? Your book reads like a blueprint for budding forgers.

I did a lot of research, and it's so fascinating. Plus, it's easy to do research now, and I have an academic background, so it comes naturally. I read The Art Forger's Handbook--the stuff about baking the layers of paint is all true. Pretty much all of the specifics about forgery, painting and the Gardner heist are true. When you really get into the research, there is so much information, you have to ramp it down. You have to make sure your research isn't showing, but it's hard to leave things out when you're so taken with them. I'm now terrified that my new book--about Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner--won't work. As my writing group has always said, "There is no insecurity too obscure...."

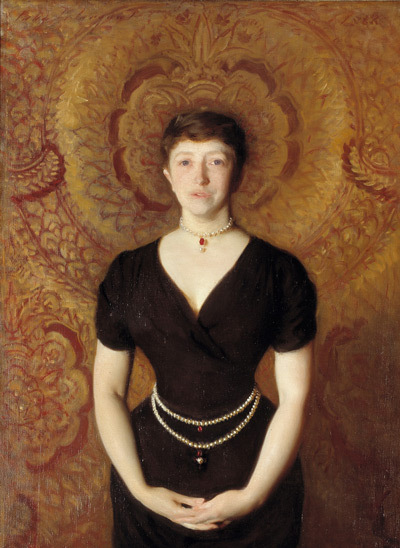

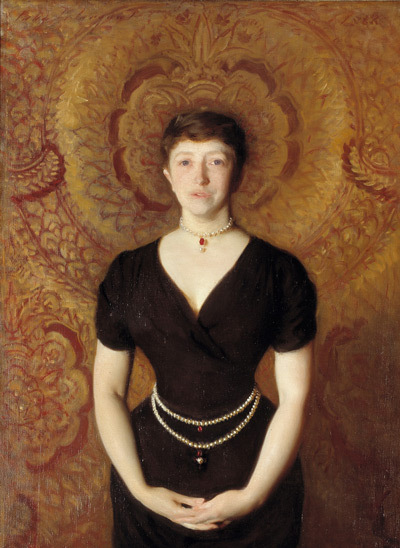

Isabella Stewart Gardner is such an entrancing and vivid figure in The Art Forger. She collected everything, from Rembrandts to lace to ironwork sconces. And then built a Venetian villa in the middle of Boston to hold it all.

Isabella Stewart Gardner is such an entrancing and vivid figure in The Art Forger. She collected everything, from Rembrandts to lace to ironwork sconces. And then built a Venetian villa in the middle of Boston to hold it all.

Isabella, or Belle as her friends called her, had an incredible eye for art, and the money (until the end) to pursue her obsession. She and her husband had a large townhouse in Boston that became so crammed with art that they could barely move. So they bought the house next door to expand, and 10 years later it was filled, too. That's when she decided to build her museum.

I recently read a book about really creative people with bipolar disorders and other types of mental illness. Belle was driven by a passion that you wouldn't call mentally healthy by any criteria, but if she had been completely sane, we wouldn't have the Gardner Museum. Nor would we have many of the artworks that hang there. Circumstance and time have a lot to do with whether a person is considered crazy or talented.

Toward the end of her life, Belle suffered a series of strokes that limited her mobility. But what's very surprising to most people is that she was forced to live quite frugally, almost starving herself in order to have enough money to preserve her museum after her death. Her will created an endowment along with stipulations for the Gardner that are eccentric, to say the least. For example, she decreed that every piece of artwork must stay in exactly the same place as it was when she died. Nothing could be added or changed.

The letters that she wrote to her (fictional) niece Amelia are so charming, and show a vulnerable side to a strong, opinionated woman.

They were such fun to write--and a great way to shorthand a subplot. In reality, she asked people to whom she had written letters to destroy them, but there was a batch of correspondence between Belle and Bernard Berenson that were intact. I used many of these to inform my research and writing. The trick to making up letters from over 100 years ago is to make them sound authentic without using the actual style of those days; no contemporary reader would want to read them if that style was replicated. I used some phrases and words to catch the flavor of things while not overwhelming the reader.

The infamous Gardner heist of 1990, where two thieves took 13 works of art, including Rembrandts, a Vermeer, and--of course--a Degas--has there been any sort of resolution?

The infamous Gardner heist of 1990, where two thieves took 13 works of art, including Rembrandts, a Vermeer, and--of course--a Degas--has there been any sort of resolution?

I, along with hundreds of cops, art lovers and FBI agents, have my theories about who is responsible, but so far there is no proof to back any of them up: Everyone from the Catholic Church to the IRA to the Mafia to Gardner Museum insiders and every thief and minor thug in the greater Boston area and beyond have been implicated. And it's now been 22 years since the robbery.

If I had to hazard a guess, I'd say it would be the work of the IRA, the Irish Republican Army, which was at war with the British at the time. The heist was quite sloppy and amateurish, and it seems to me that the only way someone could have managed to get away with it is if they immediately got the artworks out of the country and plunged them deep into the black market to be used as collateral for drugs, guns and/or money. Still, why haven't any of them surfaced in all this time? It doesn't make much sense, but I do think they're out there and hopefully, someday, will be returned. My fingers are crossed that whoever has them is taking care of them. --Marilyn Dahl

B.A. Shapiro: "If You Had One Year..."

As William Cronon says in the introduction, our world is filled with things we take for granted: "Only when we ask how they came to be... do we recognize how strange and wondrous they truly are." That's what Ott does with Pumpkin. When and why did we relegate the pumpkin to a twice-a-year appearance? Before the late 19th century, pumpkin appeared in beer more often than dessert, although with Lincoln's 1863 proclamation of Thanksgiving as a national holiday, the pie die was cast. In contrast to the humble, nurturing, quintessentially American pie is the jack-o'-lantern: the "wild and mischievous" master of ceremonies for pranks and trick-or-treating. But Ott doesn't just discuss dessert and Halloween; farming practices, our ideas about nature and the purity of rural life, the creation of a pumpkin that does not reproduce but is easy to paint, the infusion of pumpkin patches with moral values--all contribute to a captivating book about an iconic American symbol.

As William Cronon says in the introduction, our world is filled with things we take for granted: "Only when we ask how they came to be... do we recognize how strange and wondrous they truly are." That's what Ott does with Pumpkin. When and why did we relegate the pumpkin to a twice-a-year appearance? Before the late 19th century, pumpkin appeared in beer more often than dessert, although with Lincoln's 1863 proclamation of Thanksgiving as a national holiday, the pie die was cast. In contrast to the humble, nurturing, quintessentially American pie is the jack-o'-lantern: the "wild and mischievous" master of ceremonies for pranks and trick-or-treating. But Ott doesn't just discuss dessert and Halloween; farming practices, our ideas about nature and the purity of rural life, the creation of a pumpkin that does not reproduce but is easy to paint, the infusion of pumpkin patches with moral values--all contribute to a captivating book about an iconic American symbol.

Isabella Stewart Gardner is such an entrancing and vivid figure in The Art Forger. She collected everything, from Rembrandts to lace to ironwork sconces. And then built a Venetian villa in the middle of Boston to hold it all.

Isabella Stewart Gardner is such an entrancing and vivid figure in The Art Forger. She collected everything, from Rembrandts to lace to ironwork sconces. And then built a Venetian villa in the middle of Boston to hold it all. The infamous Gardner heist of 1990, where two thieves took 13 works of art, including Rembrandts, a Vermeer, and--of course--a Degas--has there been any sort of resolution?

The infamous Gardner heist of 1990, where two thieves took 13 works of art, including Rembrandts, a Vermeer, and--of course--a Degas--has there been any sort of resolution? In Chinese, the pseudonym Mo Yan means "don't speak," the advice given to him by his parents. The son of farmers, the 57-year-old Guan Moye has become famous for his epics of rural Chinese life, filled with social criticism but often laced with folklore elements. His novel, Red Sorghum, was made into an internationally famous film by Zhang Yimou, who also adapted a comic Mo Yan story into the film Happy Days. "Through a mixture of fantasy and reality, historical and social perspectives," the Swedish Academy said in the award citation, "Mo Yan has created a world reminiscent... of William Faulkner and Gabriel García Márquez, at the same time finding a departure point in old Chinese literature and in oral tradition."

In Chinese, the pseudonym Mo Yan means "don't speak," the advice given to him by his parents. The son of farmers, the 57-year-old Guan Moye has become famous for his epics of rural Chinese life, filled with social criticism but often laced with folklore elements. His novel, Red Sorghum, was made into an internationally famous film by Zhang Yimou, who also adapted a comic Mo Yan story into the film Happy Days. "Through a mixture of fantasy and reality, historical and social perspectives," the Swedish Academy said in the award citation, "Mo Yan has created a world reminiscent... of William Faulkner and Gabriel García Márquez, at the same time finding a departure point in old Chinese literature and in oral tradition."