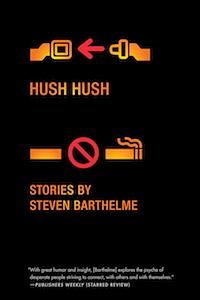

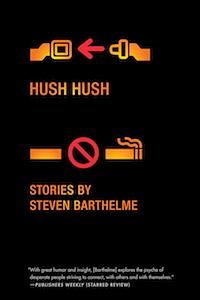

Steven Barthelme was born in 1947 in Houston, Tex., the son of the celebrated architect Donald Barthelme Sr. He is the author of the story collection And He Tells the Little Horse the Whole Story and the co-author, with his brother Frederick, of Double Down: Reflections on Gambling and Loss. He is the director of the Center for Writers at the University of Southern Mississippi, where he also teaches English. His writing has appeared in the New York Times Magazine, the Los Angeles Times, the Washington Post and McSweeney's, among others. Hush Hush, Barthelme's new story collection, was just published by Melville House.

Steven Barthelme was born in 1947 in Houston, Tex., the son of the celebrated architect Donald Barthelme Sr. He is the author of the story collection And He Tells the Little Horse the Whole Story and the co-author, with his brother Frederick, of Double Down: Reflections on Gambling and Loss. He is the director of the Center for Writers at the University of Southern Mississippi, where he also teaches English. His writing has appeared in the New York Times Magazine, the Los Angeles Times, the Washington Post and McSweeney's, among others. Hush Hush, Barthelme's new story collection, was just published by Melville House.

You have had a long and illustrious career as a short story writer. What is it about the short story that draws you, as a medium?

"Illustrious" is putting it a little grandly. I don't know what has drawn me to short stories, besides failed novels. Novels take a long time. I once read some writer saying that to write fiction you had to think you were the smartest person in the room while you were writing. It's hard to believe that for more than 10 minutes at a time, hard to believe at all past a certain age. Around 19, I'd guess. Of course, I've always lived in small rooms--that helps.

In your stories you frequently shed light on aspects of America that are often either ignored or romanticized by other literary writers--in settings that are neither urban sprawl nor suburbia, neither glamorous nor overtly repressive. Was this your goal, articulated more overtly in the satirical "The New South: Writing the Newsweek Short Story"?

Very young, I discovered that the world I saw didn't look like the one portrayed in magazines. The high seriousness and culture criticism bothered me, all that throat-clearing and frowning. I tried to describe what I saw. But trying to write anything true was difficult without some sort of corrupting self-awareness or junk heroics leaking in. When I read Jean Rhys's early novels, I thought, Christ, this is it--everyone else is lying, insufferably artificial. Hemingway, a great writer by any standard, looked like a fake.

What motivated you to write such a satire?

There's a lot about journalism in there. The fiction I most dislike is false in the same way, as if you're going to capture the culture by reporting some suburban [or ghetto] family's life story. In the suburb where I grew up, every house was full of strange folks, no two alike. Scott Fitzgerald says somewhere, "Set out to create an individual and you find you've created a type; set out to create a type, and you find that you've created--nothing." The story's statements are all misrepresentations which are being continuously turned over, as practically everything in it is stated then revised, qualified, denied, discredited. I'd like to write a novel that way.

In your stories there is often an element of breaking away from the entrenched social order--sometimes through the literal breakage of objects, such as in "Hush Hush" and "Vexed." In "Interview," Quinn breaks from the life of comfortable materialism as a lawyer. Does this seemingly recurrent theme have personal significance for you?

It must. It's really a rejection of success. Imagined success--I was a success of a kind in high school but since then success has been thin on the ground. So I may write about people rejecting success, but I have no idea if that actually works, makes for joy.

In "Claire," "In the Rain" and "Ask Again Later," a cat seems to act as the symbolic alter ego of the protagonist--lost, injured, in need of care--while the protagonist himself has trouble expressing emotion. What do you think it is about animals that makes them an effective symbol for repressed emotion?

In "Claire," "In the Rain" and "Ask Again Later," a cat seems to act as the symbolic alter ego of the protagonist--lost, injured, in need of care--while the protagonist himself has trouble expressing emotion. What do you think it is about animals that makes them an effective symbol for repressed emotion?

Well, maybe. I don't know that they are symbols of repressed emotion. One's relations with other species are surely limited, but also kind of pure. I love animals, always have, all kinds. I love skinks. But especially cats. Limited, I understand them and they understand me. They're not people. I'm not sure it amounts to any more than that.

In "Hush Hush" the protagonist breaks one of the most universally enforced taboos, along with much of his bright new home furnishings. Did this frank story of incest lead to any controversy when it was first published in Boulevard?

Of course, I wondered if it might, but it didn't.

In "Claire," "Interview" and "Hush Hush," money becomes a source of discontent for the character, with financial success corresponding to feelings of malaise. Do you think contemporary American society places too much emphasis on the attainment of money as a goal for life?

Money is not these folks' main problem. Money is a side issue. It is true that the deals they've made to make a living, in two of those stories, have led to a kind of falseness. Fraudulence is their main problem. Tilden, in "Hush Hush," is supposed to be in a different bind.

Society is complicated, bewildering. I'm uncomfortable talking about it. Seems to me there's almost nothing one can say about it in a general way that is worth paying attention to. My fellow professors don't share this view, nor do many writers.

On money, I can tell you that walking around a casino with $4,000 in hundreds folded up in your shirt pocket is a buzz, and you should give money to guys on street corners. Past that, Mae West said 80 years ago, "I've been rich and I've been poor, and let me tell you, honey, rich is better."

"Heaven" is a devastating satire of a self-important artist. A contrasting parallel is "Acquaintance," where Quinn comes face to face with the writer he could have been, and finds that it's someone very ordinary like himself. Both stories, in different ways, seem like attempts to demystify the popular idea that artists exist in a world apart.

Well read on your part. I was raised in the religion of art so maybe I'm a little sensitive there. I like some stories, poems, paintings, jokes, but I kinda hate art, or the religion anyway, so I'm a little schizophrenic. I like Dave Hickey's take on all this, and if I really understood what he's saying all the time, which I don't, I think that could resolve my problem.

Quinn is supposed to love the guy he finds as the "writer he could've been," Ethan, and the reader is supposed to love him, too. He's ordinary only in the sense that Jesus was ordinary. He's a good soul, and all the light that's falling is falling on his idealism, his love of the girl, his admiration for the dead mentor. Or at least that was how it was supposed to work. --Ilana Teitelbaum, book reviewer at the Huffington Post

Steven Barthelme: The World as He Sees It

Martinez was surprised: "My phone started glowing around 6 a.m., and I happened to be awake. My first thought was, 'Wow; those bill collectors are starting much earlier nowadays,' and I ignored it because I didn't recognize the number, until it went off again about five minutes later and it was my agent, Alice.... I depend on her to translate most of what happens in this business because I'm so new at it, and I was registering some serious excitement, but I didn't know how to interpret it. I mean... it just wasn't computing that I was A FINALIST for THE NATIONAL BOOK AWARD. What's really funny is, when you read through that list, it's almost like the writers are putting question marks behind my name and book title, like 'Who the hell is this guy??' "

Martinez was surprised: "My phone started glowing around 6 a.m., and I happened to be awake. My first thought was, 'Wow; those bill collectors are starting much earlier nowadays,' and I ignored it because I didn't recognize the number, until it went off again about five minutes later and it was my agent, Alice.... I depend on her to translate most of what happens in this business because I'm so new at it, and I was registering some serious excitement, but I didn't know how to interpret it. I mean... it just wasn't computing that I was A FINALIST for THE NATIONAL BOOK AWARD. What's really funny is, when you read through that list, it's almost like the writers are putting question marks behind my name and book title, like 'Who the hell is this guy??' "

Steven Barthelme was born in 1947 in Houston, Tex., the son of the celebrated architect Donald Barthelme Sr. He is the author of the story collection And He Tells the Little Horse the Whole Story and the co-author, with his brother Frederick, of Double Down: Reflections on Gambling and Loss. He is the director of the Center for Writers at the University of Southern Mississippi, where he also teaches English. His writing has appeared in the New York Times Magazine, the Los Angeles Times, the Washington Post and McSweeney's, among others. Hush Hush, Barthelme's new story collection, was just published by Melville House.

Steven Barthelme was born in 1947 in Houston, Tex., the son of the celebrated architect Donald Barthelme Sr. He is the author of the story collection And He Tells the Little Horse the Whole Story and the co-author, with his brother Frederick, of Double Down: Reflections on Gambling and Loss. He is the director of the Center for Writers at the University of Southern Mississippi, where he also teaches English. His writing has appeared in the New York Times Magazine, the Los Angeles Times, the Washington Post and McSweeney's, among others. Hush Hush, Barthelme's new story collection, was just published by Melville House. In "Claire," "In the Rain" and "Ask Again Later," a cat seems to act as the symbolic alter ego of the protagonist--lost, injured, in need of care--while the protagonist himself has trouble expressing emotion. What do you think it is about animals that makes them an effective symbol for repressed emotion?

In "Claire," "In the Rain" and "Ask Again Later," a cat seems to act as the symbolic alter ego of the protagonist--lost, injured, in need of care--while the protagonist himself has trouble expressing emotion. What do you think it is about animals that makes them an effective symbol for repressed emotion?