|

| photo: Kolin Smith |

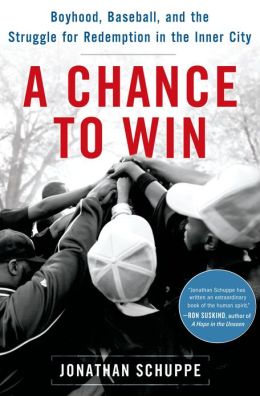

Jonathan Schuppe built his journalism career at the Newark, N.J., Star-Ledger, investigating politics, government and crime. He was part of a team of reporters that received a 2005 Pulitzer Prize for coverage of Gov. James E. McGreevey's resignation. At the end of 2008, Schuppe took a buy-out from the Star-Ledger and began working on his debut book, A Chance to Win, just published by Holt (see our review below), which grew out of a story he covered for the newspaper about a former drug dealer trying to turn his life around as a Little League coach. His passion for the story is evident in the pages of his book and in his dedication to see it through. These days, in addition to publishing his book, Schuppe is a senior correspondent for NBCUniversal's local news websites and serves on the board of directors of Criminal Justice Journalists.

You wrote many articles during your career. Why did this one, about a former drug dealer and Little League in Newark, turn into your first book?

There were very few stories I wrote as a crime reporter that focused on the admirable aspects of life in Newark. Rodney and the Eagles touched me in a way that none of my prior subjects had. I grew to care deeply for them, and wanted to know how things turned out. The huge public response to the article persuaded me that readers did, too. I began to see that the characters were in many ways representative of Newark's story. And the timing was right: the summer the article was published, the owners of the Star-Ledger needed a bunch of people to take buyouts or the paper would close. I took it as an opportunity to pursue a book deal.

You mention that developing friendships with people you write articles about is frowned upon, yet you and Rodney developed a close relationship. What made this a different situation?

It's fairly simple to write a newspaper article, even one that involves months of reporting, and maintain the classic hard-news reporter's detachment. But the type of book I wanted to write required gaining deep access to Rodney's personal life. That could come only by spending immense amounts of time with him. The more I hung out, the closer we became. I considered taking the traditional route by refusing to insert myself in the daily events of his life. But that felt less honest than the alternative, which was to throw myself into Rodney's journey.

I shared much of my life with him. He got to know my wife and daughter and parents. We spoke a lot about each other's hopes and worries. Several times he talked me down from bouts of extreme anxiety about the book.

There are many adults and children who were involved in the Little League program, in Rodney's life, etc. How did you narrow them down to the four that you focus on in the book?

That was a tough decision, and one I had to make fairly quickly. I agonized and fretted over the many things that could go wrong once I'd committed: people changing their minds, people moving away, people unable to open up, people having unfair expectations of what their involvement would mean for them.

Rodney was an obvious choice; he'd been the center of the story from the start. So was Derek; he had lost a parent during the 2008 season, and I wanted to know how that would affect him. He turned out to be polite and thoughtful, and his grandmother and aunt were willing to let me hang out.

I tried to follow another boy, Mubarrak, who'd also lost a parent during the season, but his family wasn't as open to sharing the experience with me. I started to focus on a third boy, Delonte, but just as I was really getting to know him, he and his mother abruptly moved away.

Fortunately, I also found DeWan. He was so charismatic and poised, and so talented, that I knew fairly early that it would be a mistake not to try to tell his story. I'm indebted to his mother, an English teacher, who understood what I was trying to do, and welcomed me into their home.

I decided on Thaiquan much later. I knew him from my earliest days reporting on the Eagles, but I didn't consider making him a major character until I learned more about his story and recognized how it could enrich the book.

Tell us how you gather information.

Tell us how you gather information.

It started with a lot of hanging out. I let everyone get to know me and ask me questions. I had the advantage of having already published an article about the Eagles' first season, so they knew on a basic level what I was about.

Eventually I reached a point where I knew there was a certain level of comfort. At one point, after I'd asked her for the umpteenth time for permission to talk to DeWan again, DeWan's mother said something to the effect of, "Stop bugging me, I trust you."

I took notes from the start. I tried to keep a notepad or laptop or digital recorder handy, but sometimes I relied on my memory.

Then there was the secondary reporting: researching the history of the neighborhood, piecing together people's backstories, interviewing teachers, doctors, clergy, friends, relatives. I got kind of obsessive and ended up spending weeks on tangents that never made it into the book.

This went on for a couple years, until I realized that my deadline was approaching and I needed to extract myself and start writing. I waited too long to do this.

It took about a year to complete a first draft. I wrote a lot of drafts, too many to count. I blew a couple deadlines. My editor was very understanding. But she finally told me: enough, hand it in.

What was most challenging in shifting from news articles to a book?

Maintaining focus. I'd never had to work so long on a single subject. When I originally decided to pursue a book deal, I did it on the naïve assumption that I could take a buyout from my newspaper and spend a year finishing my reporting. That was in the fall of 2008, and boy, was I wrong. Today, when someone asks me advice about book writing, I tell them to make sure they are passionate enough about their subject to sustain years of immersive, grinding work.

Was there anything you learned or discovered in this process that surprised you?

I was often shaken by the spurts of brutal violence, some of which directly impacted the people I was writing about, some of which occurred in the background but were still traumatizing. The death of Darnell. The fatal drive-by outside Carmel Towers. The gunfire that injured the young boy riding his bike. The October night of gang-related shootings that had many kids afraid to go outside.

I'm also surprised at the strength of the relationships I developed. I began my reporting while learning how to be a father myself. I believe that I'm a better man, and a better dad, for knowing Rodney, the boys and their families. I did not expect that to happen.

What was the most rewarding experience related to the book?

I took great pleasure in watching Rodney overcome near-debilitating bouts of self-doubt to achieve what may seem to be very modest victories. There were many such moments, but one that comes immediately to mind was in the fall of 2008, when Rodney was introduced at a charity fund-raiser with an ABC World News piece on the Eagles. When the lights went up, the audience gave him a standing ovation. He never expected to do anything worthy of such praise. I can still feel the goosebumps on my arms.

The most disappointing?

Earlier, I mentioned my inability to detach myself emotionally from the people whose lives I was documenting. A consequence of that was having overly optimistic expectations of what Rodney could achieve beyond the Little League field. Rodney spoke openly about his hopes of finding a job, expanding his mentoring work, coaching at a higher level. I underestimated how difficult it was for him to accomplish such things. %o people like me, who have lived less complicated lives, these things seem routine. I learned that they are not.

In the book's prologue you write that this story doesn't have a tidy ending and that for the young boys this is just the beginning. Will you follow up on the lives of these individuals or are their stories told now?

I don't expect to continue writing about them. But I still want to know how things turn out. I still care deeply about all of them, and I hope to remain in their lives. --Jen Forbus of Jen's Book Thoughts

Jonathan Schuppe: From Crime Reporting to an Admirable Story

"The most touching moments at events have been when people come up to me, often close to tears, saying, You got my son reading, my husband reading, or my wife reading for the first time. I've been putting programs in motion to re-create a nation of people who love to read.

"The most touching moments at events have been when people come up to me, often close to tears, saying, You got my son reading, my husband reading, or my wife reading for the first time. I've been putting programs in motion to re-create a nation of people who love to read.

Tell us how you gather information.

Tell us how you gather information.