|

| photo: Richard Dubois |

Kenneth Bonert's fiction has appeared in McSweeney's, Grain and the Fiddlehead, and his journalism has appeared in the Globe and Mail, the National Post and other publications. His story "Packers and Movers" was shortlisted for Canada's Journey Prize. Born in South Africa, Bonert is the grandson of Lithuanian immigrants. He lives in Toronto.

Prior to this novel you wrote short stories. How did they prepare you to write your first novel?

When I began to write fiction, I wrote many short, fantastical, allegorical pieces in the style of Kafka. I experimented with language and form; some of these came close to being published but ultimately were not. I gradually began to write longer, more realistic stories drawn more directly from my own life's experiences. This wasn't a conscious or strategic decision, just a progression that flowed naturally from the work.

The first story I published was about a Jewish family leaving South Africa, set in the late '80s. I think the story worked because the characters were very real to me; the story showed how wider political forces were squeezing one family, moulding the life of the young protagonist. It had a harsh energy and raw feel to it that I liked. I had become very interested in voice and dialogue and I began to see the potential in making use of the slangy mishmash of languages that I had grown up with. The success of that story--it was shortlisted for a major award--showed me that I was on the right track.

I published other South African pieces, then decided to stretch into new territory with a novella set in Bosnia during the war there in the mid-'90s. (I had visited the conflict as a reporter for a small Canadian newspaper.) All of this short fiction helped to build up my capacity to tackle a novel in the same way that running progressively longer distances can prepare a jogger to take on a marathon. It built up my patience and resolve, and helped to shore up my confidence that the work I was interested in doing could find an audience.

The novel is huge, coming in at some 550 pages. When you started out did you think it would end up being that long?

The original idea that I had for the novel was a kind of triptych: the first part would be set in Lithuania and would feature a character who dies there; the second part would be a character who emigrates; and the last would be about the new generation born in South Africa.

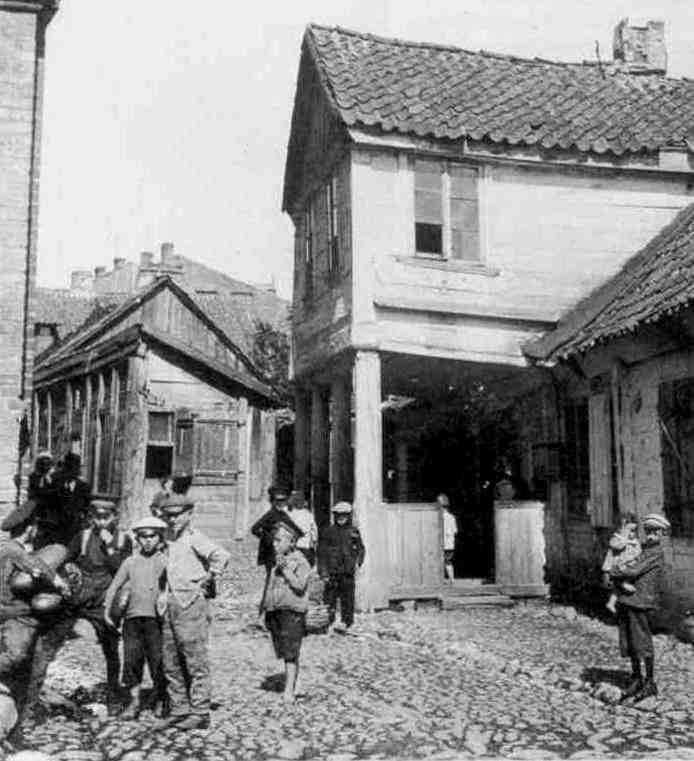

As I worked on this, I found the characters had more and more to say, events and insights accumulated, and the story expanded until it was too big for a single book. So I thought of a trilogy of novels. I wrote the first novel of this projected trilogy, set in the shtetl of Dusat in Lithuania, but was not satisfied with it. Then I worked on the emigration story and began to write about a certain Isaac Helger. I struggled for a time to find his voice, but once I tried the present tense he came alive on the page to me and soon became the dynamic centre of the entire project, which coalesced into a single novel, The Lion Seeker.

The work I'd done on the shtetl novel was not wasted: it gave me depth and background, and an interesting way to render Yiddish into English. This background became the substance of Isaac's story, a secret past that he discovers as we advance with him through the narrative.

The work I'd done on the shtetl novel was not wasted: it gave me depth and background, and an interesting way to render Yiddish into English. This background became the substance of Isaac's story, a secret past that he discovers as we advance with him through the narrative.

I don't think I had any particular length in mind, though I was conscious that it was becoming a long book as I wrote it. I think as long as the narrative is well-paced and suspenseful, as long as the writing holds up and draws the reader forward, a long book can only be a bonus. (Also it's perhaps worth noting that the length of pages can be a slightly misleading measure: a book as dialogue-heavy as The Lion Seeker, for example, contains a lot of white space.)

Stylistically, one of the fascinating things about the book is your use of many languages, terms, and phrases. Did it present any particular challenges?

South Africa is a country with 11 official languages, not to mention the multitude of tongues spoken by immigrants, present and past (such as Yiddish). One of my main aesthetic goals for The Lion Seeker was to find a unique way to capture the authentic feel and sound of South African speech in all of its many idioms and vernaculars.

A lot of South African literature, I have found, uses a kind of highbrow British-accented speech, and I wanted to break with that and get to the gritty everyday slang of ordinary people. I wanted to stick with the authentic terms and to capture the way that people, particularly emigrants, glide between the various dialects. The challenge was to pull that off without becoming opaque or cryptic. I worked a long time at getting this right.

I chose to use long dashes instead of quotation marks as direct speech markers in order to visually demonstrate this fluid movement between languages. Also, with no quotation marks to break up the text there is less of a separation between translated words and direct speech. It has always been interesting to me that language, like water, has a way of flowing around obstacles between people, so that even though ethnic groups were ostensibly segregated in South Africa, the speech of everyday life tended to argue against the legitimacy of this apartness.

A lot of the dialogue in The Lion Seeker is translated Yiddish. I wanted to find an interesting way to capture the flavour of the original without sounding clichéd. I had in mind something akin to that which Ernest Hemingway had accomplished in For Whom The Bell Tolls where the decorous, formal feeling of Spanish is retained in the English translation (sometimes by being quite literal, using thee and thou, for example). John Hersey in the novel The Wall had also done some interesting translating of Yiddish that made me alive to other possibilities. I was able to refine my own method during the early novel draft that was set wholly in a Lithuanian shtetl.

Is your main character, Isaac Helger, autobiographical? Can you talk a little about your Jewish heritage and the Lithuanian connection as it relates to the novel?

Is your main character, Isaac Helger, autobiographical? Can you talk a little about your Jewish heritage and the Lithuanian connection as it relates to the novel?

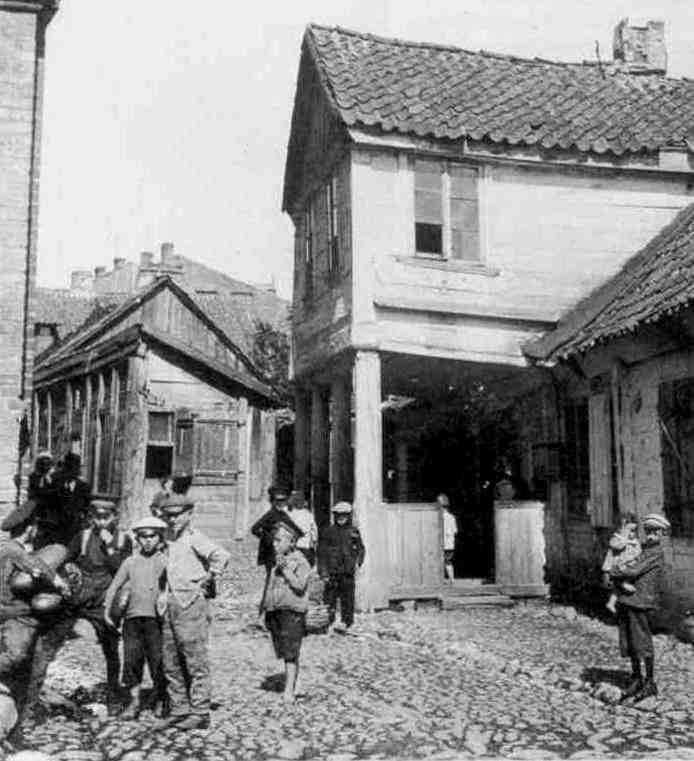

I grew up in a household that included my late grandmother, a woman born in 1901 in the village of Dusat in Lithuania, who later emigrated to South Africa with her two young boys. Bohbee, as we called her, spoke only Yiddish. I was close to her, and grew up steeped in her nostalgic stories of the old country. The village, with its frozen lakes and snow-covered forests, always seemed to me, sitting with her in our suburban garden under the hot African skies, to be a fairy-tale kind of place, not quite real but entirely fascinating. Part of my motivation for writing this book was to research the reality of what Dusat had been, to compare the facts to the mythological village that existed in my imagination

I also grew up listening to my late uncles, who would visit my grandmother every Sunday without fail. They had both dropped out of school and come up poor in Johannesburg, both eventually becoming businessmen in the auto industry. In fact, the autowreck company that one of them founded is still in operation under the family name in Johannesburg today, though he sold it a long time ago.

I think this latter uncle in particular made a profound impression on me. He was a tough, forceful character who had fought in the Second World War and worked as a panelbeater before starting his own body shop. Some of the inspiration behind the character of Isaac Helger can certainly be traced back to him.

The complex portrait you paint of Gitelle, Isaac's mother, is superb. Where did she come from? How difficult was it to bring her to life, the good and the bad?

Gitelle was a character that was entirely invented.

The Yiddish-speaking grandmother that I had in real life was a very gentle and loving soul, sweet-natured and soft-spoken, a woman who was always baking treats for her grandkids. When it came to creating a mother figure for Isaac Helger, I decided to form a character who was the exact opposite of my grandmother. However, in early drafts I found this woman to be too flat and nasty to be believable. I had to let go of any kind of a scheme that I had, and instead allow Gitelle to emerge organically from the scenes I was writing, from the history I had made for her, the life she had been through.

In the end, writing the last chapter in which she appears was emotional for me; the character had acquired enough depth that she was alive, and I was full of sympathy and sadness for her predicament.

What do you want to achieve with this book?

I think overall with The Lion Seeker I want to achieve a balance between serious insight and poetic expression on the one hand, and telling a ripping good story that will completely absorb the reader on the other. I think my literary ideal is to try to achieve a perfect combination of these two impulses.

What about the book's literary influences? Is there some of Saul Bellow's Augie March here, or some Robert Stone? Did any South African authors, like Nadine Gordimer (her father was a watchmaker from Lithuania, just like Isaac's father) influence you and the writing of this novel?

The Lion Seeker perhaps represents a mixing of different literary lineages, an attempt to produce something unique that has not been done before by taking more familiar stories and giving them a new twist.

The Jewish-American story has a long and wonderfully distinguished tradition that I admire. Writers such as Saul Bellow, Philip Roth, Bernard Malamud, Cynthia Ozick, Mordechai Richler (Canadian), Budd Schulberg, Isaac Bashevis Singer and others, have produced a body of work that at its best crackles with verbal energy, sardonic humour and exuberant intelligence.

But The Lion Seeker concerns a different Jewish experience. An African one. I wanted to borrow the focus of these other writers in order to bring to life the Jewish community that I come from, a community that has not previously been represented in literature. I wanted to bring to literature a new kind of character, tough African Jews, sharing the same Ashkenazi background as more familiar characters yet owning profound differences, too--an exotic branch of the Jewish family tree.

Most of all, I wanted to try to create a main character in Isaac Helger that would be so unforgettably vivid and memorable that he could transcend the book and become known as a unique figure in literature in his own right.

I would say compared to South African literary antecedents, The Lion Seeker represents a break with Southern African writers who have over the past decades been concerned almost exclusively with the politics of racial oppression. (Writers such as Doris Lessing, J.M. Coetzee and Nadine Gordimer, all of whom have won the Nobel Prize.) Now that apartheid is on the scrap heap of history where it belongs, it seems to me there exists a new cultural space for South African writers to tell other kinds of stories, and the Jewish experience in South Africa is the one that I've chosen to go back and to explore. Not that the politics of race are avoided--that would be impossible--but they form only one element (albeit a major one) of Isaac's story.

As a writer, are there some books that you reread regularly to prime your creative juices, or just because you love them?

There are many that I'll pick up and dip into for just that reason. Tolstoy's short novels and Hemingway's short stories share a certain quality of flawless truthfulness for me that brings me back to them time and again. There are also some big books that I read when I was younger that bring back a good feeling when I read them again now--James Jones's Go to the Widow-Maker is one of them. John Updike's Rabbit Redux and Rabbit at Rest are two more. Robert Stone's A Flag For Sunrise always seems to have the power to draw me in. Don Delillo's End Zone is a short one, but lovely indeed to dive through.

What's next for you?

I'm polishing a collection of short fiction, and finishing a draft of my next novel. --Tom Lavoie

Kenneth Bonert: Balancing Act

She shares with readers the texts that have taught her how to approach humor (such as Bill Bryson's A Walk in the Woods), childhood memories (The Liar's Club by Mary Karr; Autobiography of a Face by Lucy Grealy) and boundaries: "With Just Kids, Patti Smith teaches how much room memoir can make to preserve the integrity (and privacy) of others," Kephart writes.

She shares with readers the texts that have taught her how to approach humor (such as Bill Bryson's A Walk in the Woods), childhood memories (The Liar's Club by Mary Karr; Autobiography of a Face by Lucy Grealy) and boundaries: "With Just Kids, Patti Smith teaches how much room memoir can make to preserve the integrity (and privacy) of others," Kephart writes.

How did this volume come together? Were there any guidelines you gave the authors?

How did this volume come together? Were there any guidelines you gave the authors?

The work I'd done on the shtetl novel was not wasted: it gave me depth and background, and an interesting way to render Yiddish into English. This background became the substance of Isaac's story, a secret past that he discovers as we advance with him through the narrative.

The work I'd done on the shtetl novel was not wasted: it gave me depth and background, and an interesting way to render Yiddish into English. This background became the substance of Isaac's story, a secret past that he discovers as we advance with him through the narrative. Is your main character, Isaac Helger, autobiographical? Can you talk a little about your Jewish heritage and the Lithuanian connection as it relates to the novel?

Is your main character, Isaac Helger, autobiographical? Can you talk a little about your Jewish heritage and the Lithuanian connection as it relates to the novel?