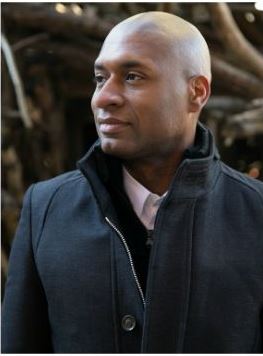

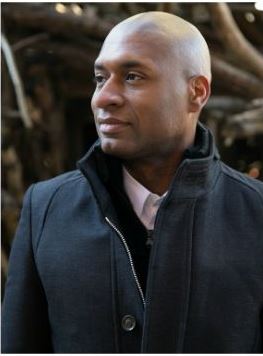

Charles M. Blow has been a columnist at the New York Times since 2008, is a CNN commentator, and has appeared on MSNBC, CNN, Fox News, Al Jazeera and HBO. Blow lives in Brooklyn with his three children. We recently talked with him about poverty and race in America, life as a single parent, and the experiences that led him to write his upcoming memoir.

Charles M. Blow has been a columnist at the New York Times since 2008, is a CNN commentator, and has appeared on MSNBC, CNN, Fox News, Al Jazeera and HBO. Blow lives in Brooklyn with his three children. We recently talked with him about poverty and race in America, life as a single parent, and the experiences that led him to write his upcoming memoir.

How did you decide to write something so intensely personal?

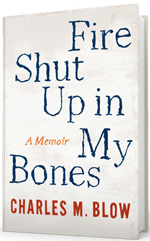

I'm not sure if I decided to write a memoir as much as the form chose me. I began writing this book before I knew I was writing it. I had an extraordinarily long commute, so I began writing short autobiographical essays that I thought I might be able to submit to a magazine for publication. In 2009, that all changed. That year, two 11-year-old boys, Carl Joseph Walker-Hoover and Jaheem Herrera, both hanged themselves--just 10 days apart--after experiencing unrelenting homophobic bullying.

I thought: Not on my watch. I knew then that I didn't just need to write scenes from my life, but the whole narrative arc of it, so that I could speak to the pain that Carl and Jaheem must have felt and to help other children--and adults--like them.

What do you hope readers will take away from your book?

I have so many hopes. One is the old cliché that even in the darkness you can see the light, and you can find a way to survive. One thing about children committing suicide is that they don't have the forethought to even write a note. There's nothing to say, no explanation, no examination of that pain. They don't have that language. I have that language, and I know that experience. I thought, I need to write what it feels like to walk up to the precipice that these boys walked up to, and also what happens to your life when you walk back from it. It won't be easy, but it can be done, and you can live, and you can love, and you can be whole as a human being.

Secondarily, I was thrilled that I would get a chance to write about the incredible diversity of the black male experience, all of the heroes and villains and all sorts of ways of being. I feel like in popular culture we're reduced to a perilously narrow definition of being; all men are, African American men even more so. This idea that we can be complicated and sensitive and nurturing and, conversely, cruel just as any other human being can be thrilled me to no end. I wanted to make sure that I painted all of the men as full human characters, and I'm hoping that people will see that.

And I'm hoping people will understand what poverty looks like in America. I think that we often think only of inner-city poverty, but there is also rural poverty, and it is oppressive, and it has none of the advantages of being surrounded by a city where people are philanthropic. None of that exists for the rural poor or the suburban poor, and in that is a darkness that is persistent. I think if you haven't experienced that level of poverty, you cannot even see that people can draw any joy in their lives with it because it is so startling and it is so unreal.

As a single dad raised by a single mom, how do think your mother's parenting style influenced your own?

It's a blueprint. I completely leaned on what I remember seeing of her being a single parent. For the longest time, I didn't think she slept. Because when I went to sleep she would be awake, and when I got up she would be awake and have the kids up, and I just didn't think she went to sleep!

Not only was she a single parent taking care of all of us boys and her uncle--my great-uncle--she was doing so while continuously going back to school. I don't think you can overestimate how powerful it is to see a parent getting an education while you're getting an education. I think there's an abstraction when you're a kid and the teacher's telling you, "This is going to pay off later on," but you can't see how that works. But I'm seeing it in real time with my mother, her going to night classes and getting a better job, and getting a promotion, and I'm seeing the material effects of how education changes a life, how reading changes a life, and it has a tremendous effect on me. Education was an actual ladder out of your circumstances.

Also, her perseverance in all sorts of adversity, the most extreme of which, I think, was poverty. As a teacher, I think she was making $24,000 a year. There were six of us in the house. If we didn't farm and raise vegetables and a cow or a hog or two every year, we would have starved. My mom was absolutely insistent that we would never take government assistance. I don't know if she would articulate this, but this was completely coming through the silence: that she could do it, and there was nothing that was going to keep her from being able to provide for us on her own. She used to say this thing: "You could stay in hell for one day if you knew you were going to get out." That always stuck with me when I was going through a bad time or having a hard time with the kids or whatever. You could deal with this because you knew eventually it would be over, and I live by that motto, and it is hers.

Do you think see any changes for the better in race relations now compared to when you were a child and a young adult? What do you think could help heal persistent racial divides and stereotypes in America?

There are advances, undeniably. No honest observer would deny that. But we are seeing a dangerous trend toward re-segregation, in residential communities and schools.

I was born in 1970, the year that the parish that I was in finally integrated its schools. What I saw was the experiment of people trying to integrate, and sometimes that's very difficult. What we see now is rising levels of re-segregation, particularly in schools. One study included this fact: schools in the U.S. are now more segregated than when they passed Brown v. Board of Education. That should frighten everyone. Even in the North--a recent study said that New York City schools were the most segregated of any schools in the country. That means that we don't have our children growing up having a communal experience of being with people who are unlike them, whether that's race, different incomes, whatever. I don't know how that gets rectified because it's not legislated, it is self-sorting.

From your struggles, what advice would you give a young person trying to accept him/herself?

I would say, "Difference is not deviance, and you have a moral obligation to yourself to love yourself, just as you are." --Jaclyn Fulwood

Charles M. Blow: Difference Is Not Deviance

Charles M. Blow has been a columnist at the New York Times since 2008, is a CNN commentator, and has appeared on MSNBC, CNN, Fox News, Al Jazeera and HBO. Blow lives in Brooklyn with his three children. We recently talked with him about poverty and race in America, life as a single parent, and the experiences that led him to write his upcoming memoir.

Charles M. Blow has been a columnist at the New York Times since 2008, is a CNN commentator, and has appeared on MSNBC, CNN, Fox News, Al Jazeera and HBO. Blow lives in Brooklyn with his three children. We recently talked with him about poverty and race in America, life as a single parent, and the experiences that led him to write his upcoming memoir.