|

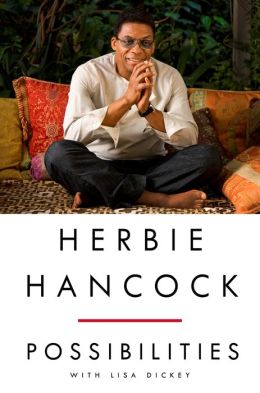

| photo: Douglas Kirkland |

Herbie Hancock is one of the major jazz musicians of the latter half of the 20th century, paying his dues with mentors like Miles Davis and Wayne Shorter. He came into his own as a bandleader in the 1970s, fusing funk, rock, blues, and pop music into his signature style with the Mwandishi Band and seminal fusion album Headhunters. He's perhaps best known by mainstream audiences for the song "Rockit," from his album Future Shock, which he played at the 1983 Grammy Awards.

He's continued to write and perform, producing diverse albums, and winning 14 Grammy awards, including 2008 Album of the Year for River: The Joni Letters.

Herbie Hancock has been a practicing Buddhist most of his adult life, and continues to be of service to young musicians as the 2014 Charles Eliot Norton Professor of Poetry at Harvard University, giving six lectures on "The Ethics of Jazz."

His memoir, Herbie Hancock: Possibilities, recalls the musician's childhood in Chicago as a young prodigy pianist, his interest in engineering and gadgetry, his discovery of jazz and playing for Miles Davis, his solo career (both before and after Davis), and his eventual explorations in funk jazz fusion. The book relates Hancock's Buddhist philosophy to music, human relationships and life in general. The final chapters reveal his struggles with drug addiction, particularly with crack cocaine, and his journey to sobriety.

One of the themes in your book is moving forward and not getting stuck in the past. You've evolved musically each and every time by letting the past go.

It takes courage to do that, too. But what's involved with that is the process of going beyond the comfort zone and exploring pasts. Because eventually, something, whatever you are doing, gets comfortable. That's when you need to break down those walls, not create new ones, because the idea is continual evolution. Continuing to learn, continuing to be open and continuing to explore.

Why do you think you're that way? Why do you and, say, Miles Davis, continually evolve, be open and just let things go?

I've had the great fortune that so many circumstances in my life have encouraged me to explore. For example, Miles Davis continually explored. He encouraged his musicians. He told us he paid us to practice on the bandstand, in the moment and in front of people, and not just kind of prepare something in our hotel room and then bring that to bandstand.

He wanted there to be truth in the music. I mean that's really the spirit of jazz: to respond to the moment. So he was a great encouragement from his activities in music, and also from what he brought from musicians in his band.

My own interest in science and innate curiosity are some of my main characteristics. That's the way I am. It pushed me in that direction. I'm an early adopter. I like tech toys. And I like trying to put things together that everybody says can't be done.

Jazz was a popular musical form when you started playing. What do you think about the current state of popular music?

It was fairly popular, sure, but it was more popular in the '20s and the '30s. Actually, once bebop came in with Charlie Parker, it was popular then, but it wasn't as popular as it had been. It was more of a connoisseur's music. Don't forget we were playing clubs in the '60s, but we weren't playing a lot of concerts. And then it evolved. There aren't many clubs anymore. Now, it's mostly concert work. It's changed, but I'm very hopeful because I see a lot of young people gravitating toward jazz. It wasn't taught in school when I was young. When I first started to play jazz, there was only Dick Grove's school. I don't know when it started, maybe in the late '40s or '50s. But now, a lot of colleges and universities have jazz programs. Some high schools have jazz programs. As a matter of fact, I'm chairman of the Thelonious Monk Institute of Jazz. We have programs in elementary schools and high schools. And it's also included in American history in a lot of schools, thanks to the Monk Institute. That is one of our programs.

What was the hardest thing in writing this book?

What was the hardest thing in writing this book?

The hardest thing for me was to expose the fact that I had a problem with freebasing on crack cocaine.

This is the first time that you've been public about that.

Right. It's the first time. As a matter of fact, I'd been really trying to suppress that. Not just forget about it, but make it go away and disappear. But that's a process of working toward denial. That's never a good thing, because things will fester; it did happen. I did experience that, I went through that. But I conquered it. And, thanks to my daughter and my wife encouraging me, I put it in the book. They said it might help some other people. That's when a light bulb went on, and I realized, I'm a Buddhist, and what we always talk about is that we practice for ourselves and we practice for others. We try to encourage other people. We have this phrase we use: "turning poison into medicine." Here's a way I can turn do that. I can transform what I went through as a struggle into a victory that I can share with other people. Perhaps I can help someone in some way.

How does that process of coming out and being public about something you struggled with affect your life?

It emphasizes the fact that I'm a human being. Although people may look at my life thinking I was born with a silver spoon in my mouth, I wasn't. Throughout the book, you can see that I wasn't. I mean I had great things, I had really encouraging parents, which is something that a lot of people don't have. That's great for your foundation of your life. My parents were always encouraging, even though we didn't have a lot of money.

I believe as a Buddhist that the whole point of life is you have the capacity for writing your own story, and not just have it written for you by external circumstances. Or by things that happened to you in the past. We all have struggles and obstacles we have to face from time to time. If we didn't have those struggles and obstacles, our lives would be really boring. There would be no victories. No way to learn. We can turn those struggles into benefits for ourselves, and for others by using them as tools for our own forward motion and our own evolution. That will make them important. That will turn them from darkness into enlightenment. --Rob LeFebvre, freelance writer and editor

Herbie Hancock: Letting go

What was the hardest thing in writing this book?

What was the hardest thing in writing this book?  The death of legendary Washington Post executive editor Ben Bradlee on

The death of legendary Washington Post executive editor Ben Bradlee on