|

| photo: Selby Frame |

Brock Clarke is the author of three previous novels, including the bestselling An Arsonist's Guide to Writers' Homes in New England, and two story collections. He is a professor in the English department at Bowdoin College, and lives in Portland, Maine.

In retaliation for a cartoonist's depiction of the Prophet Muhammad, a young Muslim man burns down the cartoonist's house. This image of fire isn't a new one in your writing. Why that m.o. this time around?

Wow, I really have to stop having people burn down houses in my fiction. Because it's not as though I'm even aware that I'm doing it, again. In this case, it just seemed like a natural, familiar, plausible form of violent protest and payback, in the way that, oh, egging or toilet papering the house would not have. But I swear I am not a pyromaniac in real life. It is not a fetish of mine. Which is possibly why I keep returning to it in fiction, fiction being a chance to, in some form, inhabit the lives of the people you are not.

Neither Jens Baedrup, the cartoonist, nor his assailant personally feel very strongly about the motivations for their actions; rather, they feel it's their job to act. Do you think this is a common issue in the world today?

I don't know that it is a common issue today, and if it were, I don't have any grand theories about why it is a common issue, and what to do about it. I do think, in the case of Jens and Søren, that it's almost as though their actions and reactions are locked in: of course Jens would draw this cartoon, because it is his job and he can't (or won't) imagine how or why anyone would react negatively to his cartoon. And of course Søren would be infuriated by Jens's inability or unwillingness to see things from the point of view of people who might react negatively to Jens's cartoon. And of course in expressing his fury, Søren wouldn't carefully consider the possible consequences of his actions, and how he might then later regret them. There are other options, is what I'm saying, and if it's true that all my fiction is about people who don't see their other options until it's mostly too late, then I guess that must be in reaction to some of the common issues in the world today.

The reader sees the book's opening event through a surveillance device in a moose head in small-town bar, but the audio is broken. This mirrors the novel in that much of what transpires is inside characters' heads, putting the other characters at a disadvantage. The breakdown in communication creates great conflict for the plot, but did it also dictate your point of view?

This is a terrific question, and I'm going be begin by answering it in the most knuckleheaded way: I've always wanted to write a novel in omniscient third person. And I tried to write both my previous two novels in that point of view, and failed dramatically and immediately, and that led me to try again in the first person. But ironically, the first 20 pages of The Happiest People in the World were initially in first person, in Jens's point of view. But they didn't work, they were already too limited, too static, and I knew then that if this novel was going to work, then I would need to see things from several characters' point of view, both because I thought they deserved their own points of view, but also because through the omniscient third person, we'd see all the things that they didn't know--about themselves, about each other. Which is one of the things I've always loved about the novels written in the third person (say, the novels by the great Muriel Spark), and which is also why I always wanted to write one. Plus, as you say, this is a novel in which secrecy and duplicity is so important, and it seemed to me the omniscient third person was the best way to emphasize and dramatize that secrecy and duplicity.

When Jens goes to Broomeville, N.Y., to assume his new identity he becomes a high school guidance counselor. You gave him this job because "who knows, exactly, what those people do?" We might say that about a number of jobs, so what made you infiltrate the mysteries of the American high school?

That's true: I'm fascinated by jobs, because I haven't had many of them. The minute I start actually doing them, I find them far less fascinating. But anyway, it's true that high schools have an outsized importance in small towns. They employ lots of people; lots of people have an attraction, or a revulsion, to those schools that long outlasts their time as students there; the town's social life--in the form of high school sports especially--revolves around the high school. It's not as though I set out to write a novel set, largely, in a high school, but I thought one of the best ways to see a small town is to see it from the point of view of people who taught, worked, ran and learned (supposedly) at the town's high school. And I thought, in a novel populated by spies, it would be great to house them in a high school, which is an institution famous for its extreme sense of secrecy and paranoia.

There's a scene in the novel where the high school band plays Pink Floyd's "Wish You Were Here." This could be the theme song for the book. Was that something you thought of prior to starting or did it occur as you were writing?

It occurred to me when I was writing it. It probably occurred to me when I was sitting in my older son's middle school band concert. It's such a sweet thing, watching this child who you love play a brass instrument in the company of other parents watching their own sweet kids whom they love play brass instruments. A sweet thing, but also a wistful thing, because you know that once they get the hell out of middle school they're never going to want to play a brass instrument again for the rest of their lives. And I thought, while I was sitting in the audience at my son's school band concert, that that sense of sweetness, and wistfulness, and longing, fit the mood of the book, and I would have to write a scene like that. As for "Wish You Were Here," you're right that it could be a theme song for the book. If there is a sadder song out there, then I do not want to know what it is. I'm pretty sure that particular Floyd classic was not in my son's school band's repertoire. But it should have been.

Jens goes into hiding in a small upstate New York city where he actually sticks out. Why not a larger metropolitan area where he would have had more chance to blend in?

Because I'm a firm believer that you should never give a character what he wants. And what Jens wants more than anything else is to blend in. And so I thought I'd put him in a small town, which would make it pretty much impossible for him to get what he wants.

You've said, "Living in a place requires some sort of lying to one's self in order to live there." In what way does that play out for you in The Happiest People in the World?

I don't remember saying that, but it sounds like something I would say, plus I don't know why you'd make something like that up, so okay, I'll pretend remembering saying that. And I think it does matter to The Happiest People: because when you move to a place, you have to lie to yourself and say, or think, Things were not so good for me in the place where I just lived, I did not like the person I was in that place. But this new place is different, and surely I'll be different there, too. Jens/Henry tells himself this lie, and so does Locs, and so, in different ways, do most of the other characters. You have to lie to yourself when you move to a new place, or when you try to start over in the same place. It's usually a short-lived, futile lie, but it's a necessary one.

The spies have a cultish feel--they gather up the outsiders/outcasts and give them a family, a unit to which they can belong--was that the aim?

It was. For me, the novel is about family, and spies are the most extreme of family units: cliquish, secretive, cultlike, protective, vindictive, self-destructive, full of love except for the moments when it is full of loathing.

You visited and loved Denmark then were upset by its portrayal when the cartoonists' scandal occurred. What made you love the country and why do you think people are found to be the "happiest" there?

I actually wasn't upset by its portrayal. I was upset, of course, with some of the cartoons and also with the violent reaction to the cartoons. But mostly, I was upset with myself: because I'd fallen in love with the place, thinking it was different (more enlightened, more peaceful, just plain happier) than other places, only to discover that it was a place much like other places, and that I was a naïve, wishful-thinking fool for believing otherwise.

But I did love the place, in part because it seems so unlikely. I mean, other than naming it the happiest place in the world, who ever talks, or thinks, about Denmark? I certainly didn't, before I went there, and this is one of the reasons I loved Denmark more than, say, northern Italy, another place I greatly enjoyed visiting: because everyone loves northern Italy. You're supposed to love northern Italy. But Denmark! Who knows how you're supposed to feel about that place! Which is why, in part, I loved it so much.

What's one element of the Danish culture you feel Americans would benefit from embracing?

The Danes often will say, in greeting one another, "Hi hi." As though one "hi" just isn't friendly enough. God, I would love it if we did that in America. Although I can imagine it would take some getting used to here. The first people who tried it might get punched in the face, or shunned.

Happiness, according to Brock Clarke, is what?

A warm gun? A cold open-faced sandwich? I'm still trying to figure that one out. Maybe the next book will have the answer. --Jen Forbus

Brock Clarke: Still Figuring Out Happiness

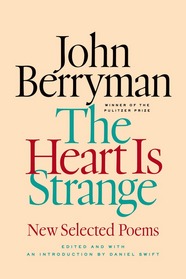

I met John Berryman's poetry in a college class, where His Toy, His Dream, His Rest was a required text ("I always wanted to be old. I wanted to say/ 'O I haven't read that for fifteen years' "). To mark the centenary of his birth, Farrar, Straus & Giroux has just published The Heart Is Strange: New Selected Poems, and is reissuing 77 Dream Songs, Berryman's Sonnets, and The Dream Songs.

I met John Berryman's poetry in a college class, where His Toy, His Dream, His Rest was a required text ("I always wanted to be old. I wanted to say/ 'O I haven't read that for fifteen years' "). To mark the centenary of his birth, Farrar, Straus & Giroux has just published The Heart Is Strange: New Selected Poems, and is reissuing 77 Dream Songs, Berryman's Sonnets, and The Dream Songs.

That was the only problem?

That was the only problem?  What was your role in the production process? What were the cool things you got to do?

What was your role in the production process? What were the cool things you got to do?

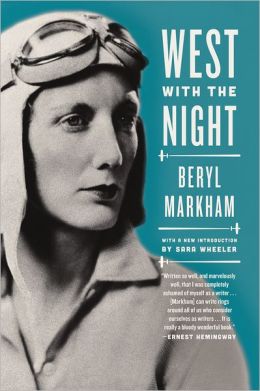

The news that a piece of Amelia Earhart's plane may have been found on an island in the Pacific made us think of that thrilling time when women aviators were regularly setting new flying records. (Earhart and her navigator, Fred Noonan, were lost in 1937 as they attempted to fly around the world). Beryl Markham was another glamorous, celebrated flyer of the era; born in England, she grew up in East Africa, was a racehorse trainer, a bush pilot and the first woman to fly solo from Europe to North America. She recounted her flights and her life in a wonderful memoir, West with the Night (North Point Press), that was originally published in 1942 but flew into oblivion. Four decades later, it was rediscovered thanks to a contemporaneous mention by Ernest Hemingway. In a letter to a friend, he wrote after reading the book that Markham "has written so well, and marvelously well, that I was completely ashamed of myself as a writer. I felt that I was simply a carpenter with words, picking up whatever was furnished on the job and nailing them together and sometimes making an okay pig pen. But this girl... can write rings around all of us who consider ourselves as writers... it really is a bloody wonderful book." He was right.

The news that a piece of Amelia Earhart's plane may have been found on an island in the Pacific made us think of that thrilling time when women aviators were regularly setting new flying records. (Earhart and her navigator, Fred Noonan, were lost in 1937 as they attempted to fly around the world). Beryl Markham was another glamorous, celebrated flyer of the era; born in England, she grew up in East Africa, was a racehorse trainer, a bush pilot and the first woman to fly solo from Europe to North America. She recounted her flights and her life in a wonderful memoir, West with the Night (North Point Press), that was originally published in 1942 but flew into oblivion. Four decades later, it was rediscovered thanks to a contemporaneous mention by Ernest Hemingway. In a letter to a friend, he wrote after reading the book that Markham "has written so well, and marvelously well, that I was completely ashamed of myself as a writer. I felt that I was simply a carpenter with words, picking up whatever was furnished on the job and nailing them together and sometimes making an okay pig pen. But this girl... can write rings around all of us who consider ourselves as writers... it really is a bloody wonderful book." He was right.