Scott Carney is an investigative journalist who has written for Foreign Policy, Details, Discover and Outside, and has been a contributing editor at Wired. The Red Market: On the Trail of the World's Organ Brokers, Bone Thieves, Blood Farmers and Child Traffickers won 2012 Clarion Award for best nonfiction book. His new book, A Death on Diamond Mountain: A True Story of Obsession, Madness, and the Path to Enlightenment (Gotham Books, March 17), tells the story of Buddhist practitioner Ian Thorson, whose trip to a remote Arizona desert retreat turned deadly.

Scott Carney is an investigative journalist who has written for Foreign Policy, Details, Discover and Outside, and has been a contributing editor at Wired. The Red Market: On the Trail of the World's Organ Brokers, Bone Thieves, Blood Farmers and Child Traffickers won 2012 Clarion Award for best nonfiction book. His new book, A Death on Diamond Mountain: A True Story of Obsession, Madness, and the Path to Enlightenment (Gotham Books, March 17), tells the story of Buddhist practitioner Ian Thorson, whose trip to a remote Arizona desert retreat turned deadly.

When did you first hear about the death of Ian Thorson and what made you decide it would be a good subject as a book?

I'd been working on this book long before I'd ever heard Ian's name. Back in 2006 I was the leader of an abroad program for American college students in India. The highlight of the trip was a silent meditation retreat in Bodh Gaya--the city where the Buddha attained enlightenment--and on the last day of the retreat one of my students took her life by jumping off the roof of the center. Some of the last words in the journal she left behind were "I am a Bodhisattva." This means that she thought she had attained enlightenment. She reasoned that taking her own life was the easiest way to speed her transition into the next world.

Dealing with the situation was probably the most pivotal moment of my life. I've written about it in a few places. However, the lingering question always was how did a meditation practice that aimed at making people more compassionate and at peace with the world turn out so badly. I looked for other cases of people whose journey into deep meditation turned tragic. I collected seven journals from people who took their own life after retreats. Then, when I was writing a story for Details about spiritual sickness, I learned about how Ian Thorson died on a meditation retreat in the mountains of Arizona and I realized that I wanted to know why someone would want to do a three-year-long retreat in the first place... and what went wrong.

Why do Westerners, and Americans in particular, sometimes have such problems when practicing Eastern religions?

America has a long history with Christianity. When Americans start getting interested in other religions, they come to table with a lot of preconceptions. It's very easy to listen to a Buddhist teaching and substitute the idea of "Nirvana" for "Heaven" or "Bodhisattva" for "Angel." In fact, it's natural to fill in the gaps of your knowledge with your previous understanding. While good teachers can head off some of this confusion, many Americans go abroad looking for answers in exotic knowledge, and that can often be a dangerous proposition. Add the prevailing sentiment of American Exceptionalism and certain meditation practices that can make you feel like a god, and some people [come to] feel that they are special and god-like. This sort of narcissism is incredibly common in certain meditation communities. If not properly taught, it's a deadly cocktail that leaves people out of touch with reality.

Are the practices dangerous or is there something in the American psyche that alters and skews things?

Are the practices dangerous or is there something in the American psyche that alters and skews things?

For most people, meditation is incredibly beneficial. It helps you concentrate, gives you a sense of well-being and has lots and lots of well-documented health benefits. Everyone comes to meditation with their own background. Life, it turns out, is a preexisting condition. And how people respond to intensive meditation has a lot to do with their own mental state before they ever hit the cushion. Americans have a lot of baggage before they ever start meditating. Cutting through that is really important.

Do you think Thorson's journey could have ended differently had he not been pulled into the orbit of Michael Roach and Christine McNally?

When Ian was at Stanford he wrote his senior thesis on the topic of spiritual intoxication. In his evaluation of the project, the eminent professor Hans Gumbrecht presciently wrote of Ian: "He is a very intelligent young man who, owing to the ease of his talents, might go extremely far. He may also perhaps never find his place 'in real life.' " So, who knows? He was a seeker and was going to find something to give him meaning in life.

One chapter provides a short history of the area in Arizona where the penultimate events took place. Is there anything about that area that foreshadowed the tragedy?

The land where Diamond Mountain University sits has a long and tumultuous history that goes all the way back to its creation in a gigantic volcanic explosion several million years ago. The freshwater spring that flows in the middle of the retreat valley was later one of the most sacred spots for the Apache, and the site of numerous murders, a battle between the Apache and the Union Army and, later, the last place that Geronimo set foot on Indian land. The people at Diamond Mountain continually refer to the Apache history, and when the freshwater spring finally dried up during the silent retreat, some people took it as a sign of very bad juju on the land.

Is there anything to prevent others from losing their way in the fringe elements of Eastern religion as taught by Americans?

Probably not. Every spiritual journey is potentially dangerous; that is part of what makes them special. I think we can raise a warning that these practices are powerful and potentially life changing, but people look for meaning however they can. Now, as Buddhist techniques like mindfulness eke their way into the American mainstream--often stripped of any historical context--I expect we will see a lot more people like Ian in the future.

How did you come up with the structure of A Death on Diamond Mountain, in which Buddhist history is interwoven with the journeys of Thorson and others?

My goal was to tell the story of Buddhism in America through the lens of this one tragic protagonist. I wanted to weave standard Buddhist teachings into the narrative as much as possible so that people would learn about the philosophy as they were absorbed in Ian's narrative. There was a lot of outlining and editing to get the mix just right.

Which writers have inspired you? Who are you trying reach with Death on Diamond Mountain?

The entire time that I wrote the manuscript I had three books on my desk that I turned to for inspiration: Jon Krakauer's Into the Wild, John Vaillant's The Tiger and Lawrence Wright's Going Clear.

I think A Death on Diamond Mountain will speak to anyone who has ever tried to strive for some sort of spiritual transcendence. I think many people have felt the cusp between madness and divinity. It's a feeling that is common to every religious experience to some degree.

You spent six years in India, more as an ethnographer than as a spiritual seeker. Is there any part of you that identifies with Thorson's yearning for transcendence? Did you ever think of practicing any Eastern religion?

I first went to India when I was in my 20s, just like Michael Roach, Christie McNally and Ian Thorson. I, too, felt the call of Eastern religions and was awestruck when I met the Dalai Lama. Even though I don't consider myself a Buddhist, I studied Tibetan Buddhism for years and have gotten a lot of wisdom out of the tradition. I have read deeply in the texts and really do believe that living life to the fullest requires getting comfortable with mortality. Part of me does want a feeling of transcendence; however, I'm also happy letting whatever divine nature humans might have or not have be a mystery until the very end. After all, it doesn't matter what happens after death--you still have to live your life in the meantime. --Donald Powell, freelance writer

Scott Carney: When Spiritual Practice Turns Deadly

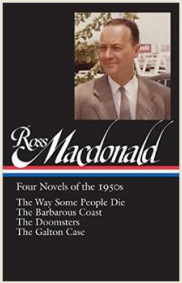

Now I can revisit one of the finest hard-boiled mystery authors with the Library of America's publication of Ross Macdonald: Four Novels of the 1950s, containing The Way Some People Die, The Barbarous Coast, The Doomsters and The Galton Case. Robert B. Parker wrote that Macdonald, "in his craft and integrity, made the detective form a vehicle for high seriousness." Macdonald also inspired later writers with his exploration of what lies beneath the façade of respectability, how family secrets fester, how the past is never truly buried, with postwar Southern California as his dark canvas.

Now I can revisit one of the finest hard-boiled mystery authors with the Library of America's publication of Ross Macdonald: Four Novels of the 1950s, containing The Way Some People Die, The Barbarous Coast, The Doomsters and The Galton Case. Robert B. Parker wrote that Macdonald, "in his craft and integrity, made the detective form a vehicle for high seriousness." Macdonald also inspired later writers with his exploration of what lies beneath the façade of respectability, how family secrets fester, how the past is never truly buried, with postwar Southern California as his dark canvas.

Are the practices dangerous or is there something in the American psyche that alters and skews things?

Are the practices dangerous or is there something in the American psyche that alters and skews things?