_Star_Black.jpeg) |

| Photo: Star Black |

Mark Doty is the author of nine books of poetry and five books of prose. He has received numerous honors, including a National Book Award for Fire to Fire: New and Selected Poems. His latest poetry collection is Deep Lane (our review is below). Doty is the director of Writers House and a Distinguished Professor of English at Rutgers University.

[Shelf Awareness would like to thank Literary Arts in Portland, Ore., where Doty read as part of the 30th anniversary Poetry Downtown program, for helping make this interview possible.]

To start at the beginning: epigraphs. Authors pay a great deal of attention to these and Deep Lane has two, from Emerson and Twain.

Epigraphs are like signposts at the base of the trail, some pointers to suggest what you might want to look out for up ahead. I chose two almost completely contradictory ones, the first a consoling notion that, when we're feeling lost, we can trust in the "divine animal" of our bodies to carry us through this world. My other quote is from Mark Twain, when Huck Finn says, "All right then, I'll go to hell." Huck means he's turning his back on social convention and the judgments of others. I like that implication, but what I really mean is that to follow the body and its desires is a double path--does it carry us through this vale of suffering, or straight to hell, or both?

Nine of the poems in your new collection are titled "Deep Lane," a street close to where you live in Amagansett, on Long Island in New York. How did this street you walk so often lead to this group of poems?

It's a really short, bucolic road where there is an exceptionally handsome organic farm. In truth, it's the name I love: the two monosyllables, the two long vowels, the sense of moving forward and down. Say the word out loud, and where do they take you? I wanted that sense of moving down into a place of interiority, maybe into the earth itself.

The concept of "home" seems to be present in many of these poems. As an "army brat" who grew up moving often from base to base, is "home" something you particularly relish now?

Lord, I have tried! I've made a number of homes--and now four gardens. My home now, and I'm guessing the one where I will stay, is here on the East End of Long Island, a green place, pretty well protected against further development, where it's possible to have ongoing encounters with box turtles and deer, wild turkeys and, this winter, a newly resident great horned owl. I have an apartment in the city, which is important for a balancing energy, and because it's much closer to my job. It would be more practical in a number of ways to just stay in the city, but my work depends on a sense of participation in cycles of growth and change. I have a beautiful unheated little house out back, and I write there whenever I can. It makes me feel that my feet are literally planted in the garden as I work; that energy moves toward me. I can never entirely feel complete in one place. Well, I can for a little while, but after a while out here I want to see human stirrings in the street, I want the flash and rush of New York. And, of course, then I get enough of that.

One of the poems is quite harrowing. "Crystal" starts at a dark place--"I am refined, my base elements / burnt away, or am I now nothing more/ than base"--only to take a turn toward a bright and uplifting place: "I mean to say the surge identified itself to me / as divine, but to whom could this poem pray?" To whom, indeed.

One of the poems is quite harrowing. "Crystal" starts at a dark place--"I am refined, my base elements / burnt away, or am I now nothing more/ than base"--only to take a turn toward a bright and uplifting place: "I mean to say the surge identified itself to me / as divine, but to whom could this poem pray?" To whom, indeed.

When I said, All right then, I'll go to hell, I meant it, in the sense that I would go head to head with a sense of futility. These poems were written in the second half of my 50s, which was the age my mother was when she died of alcoholism. I was very aware of old ghosts rising up at me, of my own aging, of coming to the end of a long relationship, of feeling--I don't know, finished. Not an uncommon feeling for a later-middle-aged man, gay or otherwise. My feelings of futility found some temporary relief in excesses of various kinds--drugs and sex--and that's what's happening in "Crystal." To whom can that poem pray? Is there a god of moderation?

In a number of poems things "lie a little beneath / the surface, now and then / turning the face up," like the sea lions, or the white fish, or radishes. Much seems to be happening in these poems at the interface of the surface or the border between below and above. Are we stronger when we send down a taproot?

Absolutely, and I like how you phrased that, I think in Deep Lane you can feel the speaker reaching downward--sometimes toward oblivion, sometimes toward strength. I know it is a very dark book, one that, in some ways, the speaker barely survives--and yet ultimately it seems to me a rather hopeful one. It tries to look the darkness right in the face, and to continue to find pleasure in the world. The hero of the book, finally, is that gnarly old tree in the final poem, which takes everything that it has twisted and bent into and transforms it into bloom. I am, of course, that contorted trunk, and these are the flowers.

Your next book is entitled What Is the Grass, also the title of one of the poems in this collection. Reflecting on Walt Whitman you write: "And he who'd written his book over and over, nearly ruin-/ ing it,/ so enchanted by what had first compelled him." What do you admire in Whitman?

He was the bravest poet America ever produced. He not only invented our free verse, using the line and the stanza to represent not some predetermined form but the very process of his own thinking--he used that new form to say astonishing things. Who could be brave enough to say, in 1845, that men and women were equal, that the self was not something contained in an individual sack of skin, but a great shared soul in which all participated, that sex was healthy and good, and that there was neither any death nor any afterlife, simply the beautiful continuing circulation of matter, in which it was our joy and privilege to participate? He was also, of course, the first modern American same-sex lover to give voice to his desires, an assertion in which I am absolutely confident and which, to my amazement, is actually still controversial today. Some scholars want to say he just fantasized, others say he was bisexual or omnisexual. For me this always brings to mind Dorothy Parker's great concluding line, in a poem that lists a bunch of lies, "And I am Marie of Rumania."

This wouldn't make a whit of a difference had he not written superb poems, especially early on. Thus my interest goes far beyond the sociological; he was an artist first, and one of the world's very finest. --Tom Lavoie, former publisher

Mark Doty: What Lies Beneath

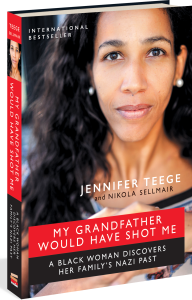

In My Grandfather Would Have Shot Me: A Black Woman Discovers Her Family's Nazi Past (The Experiment), Teege recounts her years-long struggle to come to terms with this awful personal legacy. She learned all she could about the period and her family. Full of shame and confused, for a time she was silent about it and suffered profound depression. She contacted her mother, who was still alive. She visited the Plaszow camp. She began to speak with her adopted family, with her friends in Germany, and eventually her Israeli friends. In occasional chapters, journalist Nikola Sellmair supplies historical and psychological perspective on Teege's difficult journey to know and understand her family story while creating her own identity.

In My Grandfather Would Have Shot Me: A Black Woman Discovers Her Family's Nazi Past (The Experiment), Teege recounts her years-long struggle to come to terms with this awful personal legacy. She learned all she could about the period and her family. Full of shame and confused, for a time she was silent about it and suffered profound depression. She contacted her mother, who was still alive. She visited the Plaszow camp. She began to speak with her adopted family, with her friends in Germany, and eventually her Israeli friends. In occasional chapters, journalist Nikola Sellmair supplies historical and psychological perspective on Teege's difficult journey to know and understand her family story while creating her own identity.

_Star_Black.jpeg)

One of the poems is quite harrowing. "Crystal" starts at a dark place--"I am refined, my base elements / burnt away, or am I now nothing more/ than base"--only to take a turn toward a bright and uplifting place: "I mean to say the surge identified itself to me / as divine, but to whom could this poem pray?" To whom, indeed.

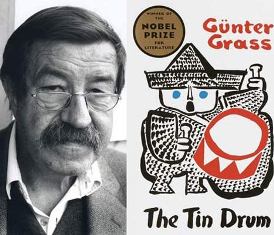

One of the poems is quite harrowing. "Crystal" starts at a dark place--"I am refined, my base elements / burnt away, or am I now nothing more/ than base"--only to take a turn toward a bright and uplifting place: "I mean to say the surge identified itself to me / as divine, but to whom could this poem pray?" To whom, indeed.  First published in 1959, The Tin Drum became a post-war classic of magical realism that in a roundabout manner tells the tortured story of Germany in the 20th century. Its author,

First published in 1959, The Tin Drum became a post-war classic of magical realism that in a roundabout manner tells the tortured story of Germany in the 20th century. Its author,