|

| photo: Emily Martin |

Historical novelist Sarah McCoy gained acclaim for her second novel, The Baker's Daughter (2012). She calls Virginia home, but currently lives in El Paso, Tex., with her husband, an army physician, and their dog. McCoy's third novel, The Mapmaker's Children (see our review below), explores the life of Sarah Brown, daughter of abolitionist John Brown, and her connections to a modern-day woman struggling with infertility.

What inspired you to write The Mapmaker's Children?

All my books have come to me differently. That's both a blessing and a curse--I don't have a formula! The Mapmaker's Children started with a line, which kept echoing in my head: "A dog is not a child." I started asking questions: Who was saying it? Where was she? That woman became Eden, the book's contemporary narrator.

The more Eden said this line, the more I heard the pain in her voice. It was a bitter statement--she was falling apart inside. I knew she wasn't in control of something important in her life. And I knew her voice was contemporary--21st century. Sarah Brown's story came later.

Did you visit any historical locales related to John Brown and his family?

I did! I went home to Virginia to visit my parents, and my dad drove me to Harpers Ferry, the scene of John Brown's raid. We walked the streets of Charles Town, the town next to Harpers Ferry. We went to the bank, the post office, the jail where Brown was held. We also went to Harpers Ferry itself and visited the museums dedicated to Civil War history. I read John Brown's letters to his wife, Mary, written while he was in prison. I also read some of his letters to his Underground Railroad colleagues.

Since I wanted to set the modern-day story in the same area, my dad and I also walked the residential streets. We drew maps, talked to locals. There were all these beautiful houses, and I knew Eden would live in one of them.

When you talked to librarians and other researchers, did you interview anyone related to John Brown?

I didn't interview any of John Brown's descendants. That was deliberate. His story is part of their heritage and their family lore. But we're so far removed from John Brown's time--it's history to the rest of us. And I did not set out to write a nonfiction, biographical account of Sarah Brown. That was not my purpose. I wanted to make that very clear.

Sarah Brown and her mother and sisters moved to California several years after John Brown's death. Did you visit their home there?

Sarah Brown and her mother and sisters moved to California several years after John Brown's death. Did you visit their home there?

I did. I visited Sarah's grave--which was a powerful experience. I could feel her spirit as I sat there, urging me on to write this book. When you are writing a story you feel a responsibility to honor the spirit of someone who really lived--it is much more of a weight in a beautiful way. It's not just storytelling; it's a tribute. I was writing about someone's legacy, and also creating my own legacy. I believe books can be a legacy, as much as children or anything else.

And I went to the Saratoga Museum in Red Bluff, Calif., which is the only place in the world that has any of Sarah's artwork on display. I purchased a pamphlet about Sarah's life--about 20 pages printed on plain computer paper. She was known as the most charismatic and attractive of all John Brown's children. I even saw a newspaper clipping to that effect! But today, there is very little information about her life.

Sarah's story in the book starts with a bout of dysentery that leaves her barren (and parallels Eden's modern-day struggle with infertility). Did that really happen?

I get that question a lot--"Did such-and-such really happen?" My answer is always that I use as much fact as I can to elevate the fiction. Sarah did have dysentery and I read that she "carried the scars" for the rest of her life. But there is no specific evidence that she was barren. She loved family and children--she later started an orphanage and served as its headmistress. But she never married and had no children. I chose to weave that incident into the story.

Eden discovers a ceramic doll head early in the book, and its history plays a pivotal role in the plot. How did you decide to bring that element in?

I love a puzzle. I love a mystery. You have all these different pieces and you have no idea how they're going to click together. I know I have smart readers, and I try to make an intellectual journey for them as well as an emotional one. The detail about dolls and the Underground Railroad was historically fascinating, but it was even more fun to weave it into the book for my readers.

Eden's husband brings home a new puppy who becomes a driving force in her life. How did you decide to include him?

I knew there was going to be a dog in the story when I started hearing that first line: "A dog is not a child." A pet is something you nurture and grow. For Eden, it's a struggle to nurture and grow a child. But the creation and development of a family unit with pets is no less worthy than having a child. Just because you don't have a child does not mean that you can't create a family.

I thought a lot about families as I was writing this book, both in terms of Eden's and Sarah's stories. And the truth is there's not just one Rubik's Cube answer, where everything lines up and this is how you constitute a good family. People suffer trying to attain that stereotype, and it often doesn't line up with their real world. I hear that story over and over from women in my generation.

It can be scary to admit that your life or family isn't turning out the way you planned.

There's something to be said for finding contentment and for forming a family that looks different than you thought it might. Eden and Sarah both learn not to be afraid of how their lives are turning out--even though it's not what they planned.

There are many parallels between Sarah and Eden.

Both of them are strong-willed and modern women for their times. Both of them want to fit into the social mold of their times, in a certain way, and yet they have a capacity for so much more.

Sarah believes that she's broken, flawed, because she can't bear children. Eden is facing the same pressures in a totally different time and context. As modern women, we think we've come a long way--and we have, in terms of education and opportunity. But now we think we have to do everything and be the best at everything. Our moms' generation drove themselves almost into the ground--are we going to make that same choice? And if we decide to do something different, are we going to be okay? Will we be judged? That's exactly what Sarah Brown had to deal with--if she took this different path and pursued her art, would she still be validated?

The idea of legacy is strong in the book, both in Sarah's and Eden's stories.

Part of the purpose in writing two intertwined narratives was to show that the generations are all tied together--that concept of a legacy. You are worthy of remembering, no matter who you are or what you're doing. If you're doing your best to live your life, what an awesome thing you're giving the world and history. --Katie Noah Gibson, blogger at Cakes, Tea and Dreams

Sarah McCoy: Writing a Legacy

The 12-year-old narrators of both Listen, Slowly by Thanhha Lai and Gone Crazy in Alabama by Rita Williams-Garcia spend the summer with their grandmothers and discover a great deal about who they are. Bà, Mai's paternal grandmother, opens up a world to the girl as the two make a pilgrimage to discover what happened to Bà's husband, missing in action during the Vietnam War. And Delphine and her two sisters travel from Brooklyn to rural Alabama. This is Williams-Garcia at her finest, laying out the complexities of family dynamics and the importance of accepting the past in order to be whole. --Jennifer M. Brown, children's editor, Shelf Awareness

The 12-year-old narrators of both Listen, Slowly by Thanhha Lai and Gone Crazy in Alabama by Rita Williams-Garcia spend the summer with their grandmothers and discover a great deal about who they are. Bà, Mai's paternal grandmother, opens up a world to the girl as the two make a pilgrimage to discover what happened to Bà's husband, missing in action during the Vietnam War. And Delphine and her two sisters travel from Brooklyn to rural Alabama. This is Williams-Garcia at her finest, laying out the complexities of family dynamics and the importance of accepting the past in order to be whole. --Jennifer M. Brown, children's editor, Shelf Awareness

Sarah Brown and her mother and sisters moved to California several years after John Brown's death. Did you visit their home there?

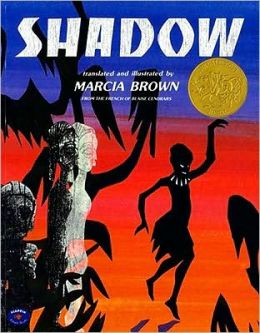

Sarah Brown and her mother and sisters moved to California several years after John Brown's death. Did you visit their home there? Brown won Caldecotts in 1955 for Cinderella, or the Little Glass Slipper (Aladdin), which she translated from Charles Perrault's version; in 1962 for Once a Mouse (Aladdin), her version of the fable from India; and in 1983 for Shadow (Atheneum Books for Young Readers), which she translated and adapted from the Blaise Cendrars poem "La Féticheuse." But these weren't the only times she was honored: she also illustrated six Caldecott Honor Books (runners-up) and won the Laura Ingalls Wilder Award for contributions to children's literature.

Brown won Caldecotts in 1955 for Cinderella, or the Little Glass Slipper (Aladdin), which she translated from Charles Perrault's version; in 1962 for Once a Mouse (Aladdin), her version of the fable from India; and in 1983 for Shadow (Atheneum Books for Young Readers), which she translated and adapted from the Blaise Cendrars poem "La Féticheuse." But these weren't the only times she was honored: she also illustrated six Caldecott Honor Books (runners-up) and won the Laura Ingalls Wilder Award for contributions to children's literature.