|

| photo: Tina Merandon |

Déborah Lévy-Bertherat lives in Paris, where she teaches comparative literature at the École Normale Supérieure. She has translated Lermontov's A Hero of Our Time and Gogol's Petersburg Stories into French. Her first novel, The Travels of Daniel Ascher, is an Indies Introduce selection for spring 2015. Lévy-Bertherat recently shared with us beautiful images that helped inspire her and thoughts on the human fascination with history.

What inspired the story of Daniel Ascher?

It took me more than 10 years to write this book. In the beginning, I had two distinct ideas: one concerned the complex relationship between a Jewish child and the family that hid him during the Second World War; the other concerned the life of a writer who created for himself a heroic alter ego in a series of adventure novels. It took some time for me to understand that these two ideas were connected, and that the writer I was imagining was the child grown up. And so Daniel Ascher was born.

His story is enriched by all sorts of treasures. I walked a lot around my neighborhood, Montparnasse, looking for traces of the past, kind of like Patrick Modiano, whom I admire very much. At Rue d'Odessa, at the bottom of a courtyard, I discovered marvelous public baths.

His story is enriched by all sorts of treasures. I walked a lot around my neighborhood, Montparnasse, looking for traces of the past, kind of like Patrick Modiano, whom I admire very much. At Rue d'Odessa, at the bottom of a courtyard, I discovered marvelous public baths.

My old Paris building, which is full of hiding places, became Daniel's home (Andreas Gurewich, the book's illustrator, came by my place to draw it!). In Auvergne, some friends showed me their attic, where two Jewish girls had been hidden; the farm owned by the Roche family, who adopted Daniel, resembles theirs.

I also slipped in fragments of the history of my friends and family. Daniel's father is a photographer, like my grandfather.

Do you think art has the power to heal grief?

I don't know if art can truly heal grief, but it can transform it and make it sublime. A great number of works have come from mourning. Victor Hugo's poems for Léopoldine, his daughter who passed away, are perhaps the most beautiful ones he's ever written.

Daniel, the writer, is incapable of telling his own story; it would be too painful--so he creates the Black Insignia series. But in closely reading these books, Hélène, his great-niece, will realize that all their young heroes are manifestations of Daniel, and that his fictions are a mask of his life. In a sense, she tracks down the lie that saved his life. There's something terrible and fascinating in the destiny of the Jewish children who were hidden: all the children play at lying, at making up stories. For a time these children had to lie continually. If they stopped playing the game, they would be lost. The game became a trap.

Daniel Ascher finds a way to overturn the trap, to gain power from it. His creative energy allows him to escape from his status as victim. At 10 years old, he's already a novelist. Writing becomes for Daniel much more than a source of consolation or resilience: he creates an entire world and offers it to thousands of young readers. His fans claim ownership over the series and identify with his characters. And this, without a doubt, is the greatest joy for a writer: that readers recognize themselves in his books. I was incredibly moved by conversations with readers who were themselves hidden children, and who told me they saw themselves in Daniel's story.

What do you think drives the human obsession with the past?

It's true that we are all obsessed with the past. Our identity is linked to memory: that of our own lives, that of our parents and grandparents, of everything that came before us. In Hélène's case, her fascination with the past comes from what she senses is a flaw in her family's history. There's a mystery that surrounds Daniel, this great-uncle who is so different from the rest of the family, the adopted child whose origins no one knows. But for a long time Hélène doesn't want to know anything, probably because she senses that for her this past has serious implications. Archeology is a detour to understanding. She will apply her methodology to family excavation: observation, patience, documentation. She ends by becoming a specialist in mosaics; symbolically, she perpetuates the reconstruction of the familial puzzle.

As someone who has translated books, how do you feel about having your own work translated?

Reading your own work in a different language is an extraordinary experience. I had the fortune of being translated by Adriana Hunter, a translator of great talent, who has worked on more than 20 novels and has won many awards. She's also someone who is very open. We spent a long time talking over the phone and I realized that my experience as a translator was very different from hers: in translating the classics (Gogol, Lermontov) I could not change one word; I had to add notes to offer clarification. Adriana could modify the text slightly to clarify certain points, like which songs were being quoted--what is evident for a French speaker may not be so for someone who speaks English.

But what is lost in one place is compensated for in others. Adriana's English is superb, and I was charmed from the very first sentences. I had the impression of rediscovering my own book, the way one rediscovers a familiar face when it's seen under a different light. I hope that the other translations will be as beautiful.

What type of research did you do for this story?

I read a lot of documents on the Occupation, particularly the testimonials of the Jewish children who were hidden (for example, the collection Paroles d'étoiles and the works of Serge and Beate Klarsfeld). I was curious to know how these children were perceived by the families who took them in. One testimonial struck me: the daughter of one of these families spoke of the difficulty of building an emotional attachment, because they didn't know how long the young refugees would be staying with them. I held on to these words, and I lent them to the character of Suzanne, the grandmother.

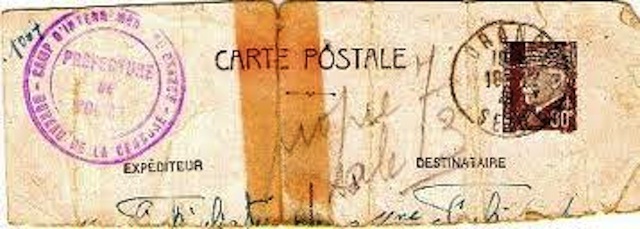

My goal wasn't to write a historical novel; I avoided explanatory scenes, but held on to everything that was exact. The big events (like the fact that the French Jews were not arrested in the mass raid on June 16, 1942--the Vel' d'Hiv roundup), but also the details (the seal on the postcards sent from the Drancy internment camp, or the magazines that the children of that time read). In the end, I had my manuscript read by a specialist, the historian Alexandre Doulut, to make sure there weren't any errors.

My goal was for Daniel's story to be realistic enough to be believed. That's why I slipped in a real historical figure, the painter Soutine. I did research on him as well; I visited an exhibition, considered his paintings. I even tried to paint the portrait that is described in the book.

What's next for you?

My second novel, Les Fiancés, is being published in France. It's the story of a passionate love that has its roots in three wars, in the world of childhood and especially in Andersen's fairy tales. --Jaclyn Fulwood

Déborah Lévy-Bertherat: The Translation of Grief

His story is enriched by all sorts of treasures. I walked a lot around my neighborhood, Montparnasse, looking for traces of the past, kind of like Patrick Modiano, whom I admire very much. At Rue d'Odessa, at the bottom of a courtyard, I discovered marvelous public baths.

His story is enriched by all sorts of treasures. I walked a lot around my neighborhood, Montparnasse, looking for traces of the past, kind of like Patrick Modiano, whom I admire very much. At Rue d'Odessa, at the bottom of a courtyard, I discovered marvelous public baths.