|

| photo: Chris Kirzeder |

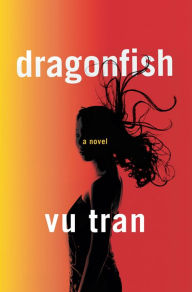

Vu Tran was born in Saigon, Vietnam, in 1975 and grew up in Tulsa, Okla. He is a graduate of the University of Tulsa, the Iowa Writer's Workshop and the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, as a Glenn Schaeffer Fellow in Fiction with a Ph.D. He is a recipient of the 2009 Whiting Writer's Award and a finalist for the Vilcek Prize for Creative Promise in Literature. He currently teaches creative writing at the University of Chicago. Dragonfish (W.W. Norton) is his first novel--"a noir page-turner resonant with the lasting reverberations of lives lost and lives remade a generation ago."

How did you come up with the idea for Dragonfish?

I was asked to contribute a story to the Las Vegas Noir anthology from Akashic Books in 2008. I'd been working on a novel for my now editor at Norton and was getting nowhere with it, so I was more than happy to dive into an entirely new story, particularly one in a genre that I'd always loved in film as well as literature. Despite my "literary" aspirations, I was also a fan of fiction that was plot-driven and atmospheric, and I quickly realized that all my stories had been mysteries in one way or another.

The mystery in the story I ended up writing, "This or Any Desert," was inspired by an old family friend who killed himself years ago: a Vietnam veteran who spent his life after Vietnam immersed in the Vietnamese community in Tulsa, where I grew up. He never married, and I think he only had Vietnamese friends, which always fascinated me--his apparent need to access a world that was essentially not his. There was something touching about it, but also sad and problematic, emotional layers that I and no one could see. I used him as a starting point for Robert, the white police officer who narrates the story and whose marriage to Suzy, a Vietnamese woman, has been both the best and worst relationship in his life.

I enjoyed writing the story more than anything I'd written in a long time, and once it appeared in the Best American Mystery Stories, I started seeing something there that could be expanded.

Your story is so thrilling because it is, in a sense, about a woman who has gone missing twice. What opportunities did that afford you as an author?

That's a great question. I'd like to think that Suzy, once she is forced to leave Vietnam, is in a perpetual state of absence, both literally and emotionally, from herself and others. In losing her first husband as well as her country, she loses touch with the person--and more importantly, the woman--she had always thought she was, a loss that proves to be as damaging as it is liberating. When she divorces Robert, she's leaving behind the woman she had become for him, and she's essentially doing the same thing with Sonny, the Vietnamese man she marries after Robert. And both times, she does not merely leave, she vanishes, and I've always thought of this as her conscious attempt at shedding who she is: as a wife, a mother, an immigrant. Much of her story in the novel is animated by this kind of existential discomfort and confusion, and so being "missing" was very much a metaphorical tool in my characterization of her.

Your setting is a character unto itself: the Vegas strip and a subculture that has not been discussed much in fiction--the Vietnamese underworld. How much was based on real life?

Your setting is a character unto itself: the Vegas strip and a subculture that has not been discussed much in fiction--the Vietnamese underworld. How much was based on real life?

A lot of it, I have to admit, was just invented. I can't say I've had much first-hand experience with the criminal element in the Vietnamese communities in Vegas, Tulsa or anywhere else I've lived. My life has been so square it hurts. But my sister and her boyfriend are cops in Texas, and from them and other sources, I have learned some things about Vietnamese gangs, especially on the West Coast.

What I also drew from was my personal encounters with a certain kind of Vietnamese male: cocky and loud, temperamental, small in size and yet unexpectedly powerful and intimidating. I saw him often when I played at the poker tables in Vegas. If you watch a lot of poker on TV like I do and you're familiar with the professional circuit, you'd also recognize this guy. He's the one playing aggressively and talking accented smack at the table. There's a certain humor and charisma there, but also an air of peevishness, a dormant belligerence. I modeled Sonny--Suzy's second husband--after this guy, but I was also interested in the different ways that he and the other Vietnamese men in the novel choose to arm themselves against people they do not trust.

Naturally, I've always been interested in Asian masculinity, particularly within Western society, how it tries to express or protect itself in a culture that tends to portray it narrowly, neuter it, or ignore it altogether.

Vietnam is another palpable setting that is never visited, only referred to in memory and the distant pasts of your characters.

Vietnam exists only in memory for these characters, and in that sense, its primary role in Dragonfish is as an animating and also debilitating shadow of who they are or believe they are. Even when they're not thinking about where they come from, they're dealing with how their origins and the conflict that brought them to America continue to shape their identity.

In my experience, if you're an older Vietnamese, then you've lived part of your life in the old country and therefore live in the new country with that part of your identity repressed in some way, distorted, maybe even slowly slipping away. If you're first or second generation, then you've lived with your parents' memories of the old country weighing on your own life, which doesn't always have a comfortable space for it. This could be the experience of any immigrant anywhere. What sets apart the Vietnamese experience in America is the seemingly insurmountable idea of Vietnam in American culture. It's rarely a country or a people in our consciousness. It's a war, a period of American trauma, a plotline for countless Hollywood movies.

I think most readers will come to Dragonfish with these latter ideas in mind, and I'm not bemoaning that or even being critical of it. But I do think that Robert embodies this mindset in the novel because that's how he's approached his relationship with Suzy, which is partly why she's always denied him access to so many things about her past. It's interesting to me how difficult it can be to connect with someone when their idea of you has been partly formed before they even met you. For all the characters in the novel, Vietnamese and American, this disconnection can be traced back to what "Vietnam" means to them, either in their memory or in their imagination.

Dragonfish is an excellent example of what literary fiction and the stylistic genre elements of thriller and crime have to offer. What can you say about your creative process and combining various aspects of different literary tropes to create something original?

I'd like to think that I wrote something that feels fresh, but I also know that countless writers of literary fiction, for over a century now, have been appropriating elements of crime and detective fiction for their own stories, some more successfully than others. I think the key for me was to respect the genre and take it seriously, to not feel as though I was borrowing from something inferior in order to create something superior. At the same time, it also felt necessary to not think of it as a genre at all, to just get in there and tell the story in a compelling, convincing, and artful way, and then let the publishing world call it what it wants, because I don't have much control over that.

My ideal reader won't care about these kinds of categories; he or she will only care about the story, the characters, and the form. When people distinguish "genre fiction" from "literary fiction," they seem to be distinguishing plot-driven fiction that doesn't care that much about form and language from idea-driven fiction that takes its artfulness much more seriously. In my mind, though, a book is either badly written or well written, boring or interesting, and there is plenty of both in all kinds of fiction.

What are you working on next?

I'm not writing at the moment. Frankly, I'm a bit too distracted by all the pre-publication stuff to write, which is exactly why everyone says you should be working on something new during this time--to at least distract yourself from the distractions. My problem is that I think a lot before starting a project and have a hard time just sitting down and writing without some kind of foundational idea. I am, however, beginning to like the idea of a novel centered on one of the characters from Dragonfish (I won't say who because that might spoil the novel). I'd like to think of it not as a sequel necessarily, but as a story that takes place in the same world but changes the center of gravity entirely.

First things first: it'd be wonderful just to have the opportunity to continue publishing. That said, I do want to continue writing about Vietnamese-Americans, because I think I write my best when I'm writing about who I am. But a Vietnamese-American is not the only thing I am, so I'd also like to tell stories that have no recognizable connection to my ethnicity. I think of it as pulling an Ishiguro. From his first to his third book, he went from writing about Japanese and Japanese-English characters to writing a novel about an English butler, but all three novels bear his DNA as distinctly as the five books that he's written since. If I can come close to doing something like that in my career, I think I could reasonably call myself successful. --Jarret Middleton

Vu Tran: Diaspora and Identity

The 1940 Wartime Golf Rules of England's Richmond Golf Club include "In Competitions, during gunfire or while bombs are falling, players may take cover without penalty for ceasing play." Satchel Paige's advice to not ever look back ("somethin' might be gainin' ") is familiar; his Rules for the Good Life also include "Go very light on vices such as carryin' on in society. The social ramble just ain't restful." Theodore Roosevelt compiled a list of 93 birds seen in Washington, D.C., during his presidency. Filmmaker Preston Sturges drew up a list of 11 Rules for Box Office Appeal, ending with "9. A baby is better than a kitten. 10. A kiss is better than a baby. 11. A pratfall is better than anything."

The 1940 Wartime Golf Rules of England's Richmond Golf Club include "In Competitions, during gunfire or while bombs are falling, players may take cover without penalty for ceasing play." Satchel Paige's advice to not ever look back ("somethin' might be gainin' ") is familiar; his Rules for the Good Life also include "Go very light on vices such as carryin' on in society. The social ramble just ain't restful." Theodore Roosevelt compiled a list of 93 birds seen in Washington, D.C., during his presidency. Filmmaker Preston Sturges drew up a list of 11 Rules for Box Office Appeal, ending with "9. A baby is better than a kitten. 10. A kiss is better than a baby. 11. A pratfall is better than anything."

Your setting is a character unto itself: the Vegas strip and a subculture that has not been discussed much in fiction--the Vietnamese underworld. How much was based on real life?

Your setting is a character unto itself: the Vegas strip and a subculture that has not been discussed much in fiction--the Vietnamese underworld. How much was based on real life? Ann Rule, whose 35 true crime books have sold more than 50 million copies in 16 languages,

Ann Rule, whose 35 true crime books have sold more than 50 million copies in 16 languages,