.jpg) |

| photo: Greg Auger |

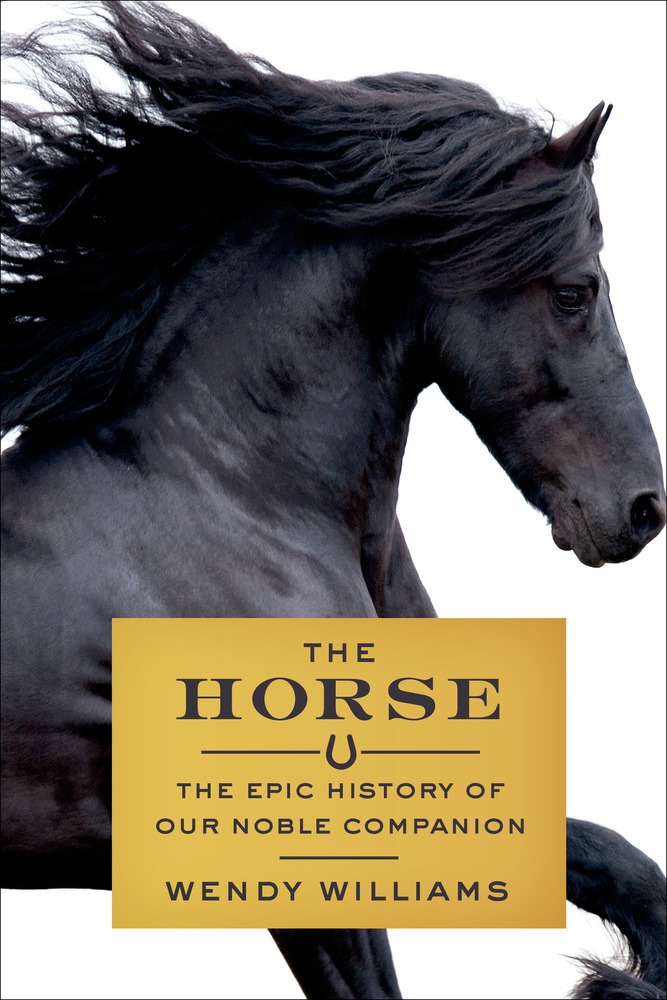

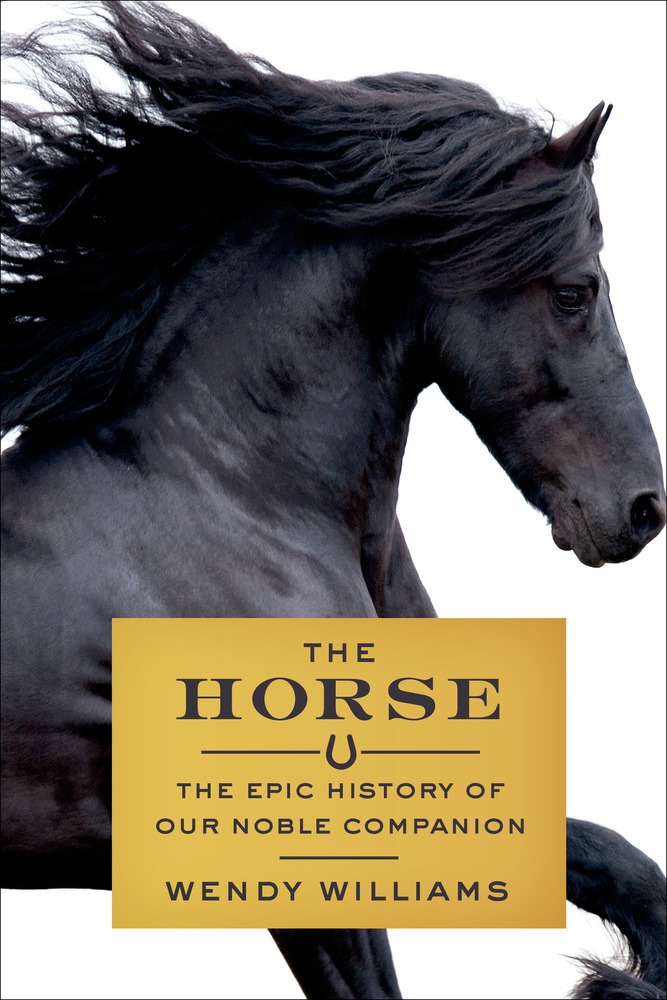

Wendy Williams is a science journalist who has written for many publications, including the Boston Globe, the Wall Street Journal and the New York Times. She is the author of several books, including Kraken: The Curious, Exciting, and Slightly Disturbing Science of Squid and Cape Wind. Her new book, The Horse: The Epic History of Our Noble Companion (reviewed below), is about the horse-human partnership and how it has evolved over time. Williams, a passionate horsewoman, lives in Mashpee, Mass.

The Horse opens with a sentence that will resonate with horse lovers everywhere: "I used to have a little half-Morgan palomino whom I most certainly did not deserve. The horse was a gem, although I was too young and too ignorant to know that at the time." Whisper's adventures return a few times throughout your work, as well as the squabbles of other horses. You strike a nice balance between personal narrative and science. Why did you include these personal anecdotes in an otherwise quite scholarly work?

I was thinking of Isak Dinesen: "I had a farm in Africa." That's from Out of Africa. So I started: "I used to have a little half-Morgan palomino whom I most certainly did not deserve." And as with Dinesen's sentence, all things flowed from there.

It's a sentence that most people who keep horses can relate to--the wish that you had done better by a horse in your care. But it's larger in scope than that. We can all relate to the regret that we didn't do the best we could have done for some living being--a pet, a friend, a child or a parent. We can't turn back the clock, but we can do something about the regret. In my case, I wrote a book.

I finally found out that many of the things that Whisper was able to do, like follow the grass on a perfect spring day, were skills that were honed by 56 million years of evolution. Whisper's ancestors endured many global crises--sudden cold spells and sudden warm spells, volcanic explosions and the like--that made him the successful living being that he was.

You ask a series of compelling questions in your prologue, including "Did [horses] have what scientists call 'theory of mind'--an ability that, among other things, lets us discern what others may be thinking...? Why are they willing to share their lives with us?"

You ask a series of compelling questions in your prologue, including "Did [horses] have what scientists call 'theory of mind'--an ability that, among other things, lets us discern what others may be thinking...? Why are they willing to share their lives with us?"

That first sentence sent me off on an excellent adventure--on travels around the globe to Mongolian horse races and to Paleolithic caves in Spain and France and on the places like Ashfall Fossil Beds in Nebraska, a site at which five different species of horses were all found intact in one place. Life on our planet is so gosh-darned fascinating, isn't it?

I think horses, for example, truly enjoy sharing their lives with us. We have a lot to give. We are expert groomers, tend to like to give out food to those around us just the way our primate relatives do, and enjoy playing as much as horses do. But I think what we have most in common is our love of speed: our ancestors used to love to swing from branch to branch in the treetops, all while the ancestors of modern horses browsed on the branches of trees just below.

You state that "horses are blessed with an exceptional cognitive flexibility that allows them to adapt to a phenomenal variety of situations.... Now that science is showing us the subtleties of how horses naturally interact with each other, we can expand our own interactions with them, improve our ability to communicate with them, and enrich our partnership." Why do you think it took us so long and do you think there will be any resistance to accepting a new understanding of horse behavior?

I once had a favorite editor, someone I greatly revered, tell me that horses were stupid. I was shocked. "Why," I asked him, "do you think that?" (Always the journalist...). He told me that he thought that way because horses let us ride them. And I do think that we are sometimes rather condescending to animals in that way, but it's really our own limitation, isn't it? Our own failure to think about the world from the animal's point of view.

|

|

Three mustang stallions at McCulloch Peaks, not far from Cody, Wyo. (photo: Greg Auger)

|

I think that horses are pretty smart and drive a hard bargain. After all, for a small amount of riding, they get fed, groomed, fussed over, played with, free medical care, dentistry.... In other words, horses are engaging in a form of mutualism, the same kind of mutualism you see on the African plains, when a bird sits on an impala's back and cleans the poor animal of ticks.

We are entering this new stage of partnership with horses because we no longer need them, for the most part. That means we can just enjoy them, the way we enjoy dogs or cats. Like those pets, horses are present in our lives as strongly bonded companions.

I imagine that I will not be the only reader that was surprised to learn that "current evidence shows that the earliest dawn horses and the earliest true primates made their grand entrance onto life's stages as a duo, one species living in the trees, the other browsing below." How much knowledge of evolution did you have when you began writing?

When I was a child, I was given books about horses. In those days, these books always included a picture of the evolution of horses, from the little dawn horses to the large, modern Equus.

Because I was five years old, I accepted that simple story as true. But 60 years later, I began to think about this. When I was visiting people in Wyoming, one of them was talking about the dawn horses and said "If they are horses...." I couldn't explain why paleontologists thought they were horses, and that annoyed me. So I set about asking some questions. I found that the dawn horses have some of the same characteristics that modern horses have, like a peculiar digestive system and a skeleton that enables the animal to run away quickly when necessary.

How is your new "backyard mustang" doing? Has writing this book changed how you approach your relationship with your new horse?

This book has certainly deepened my understanding of horses. I was taught as a child to think of the horse as a tool, and I have been very gratified to learn that this idea is no longer as prevalent as it once was. I'm in the process of adopting the mustang even as we speak. Perhaps someday I'll write a book about the experience. --Kristen Galles from Book Club Classics

Wendy Williams: Understanding Horses

The Kitchen House by Kathleen Grissom (Touchstone, $16) is the story of a white indentured servant on a Virginia tobacco farm in 1791; it was published in 2010 as a paperback original, with a modest first printing. Sheanin said, "It had an Alice Walker quote and we were publishing into The Help phenomenon, but no one expected it to be the runaway bestseller that it was." It became a New York Times bestseller and book club favorite--so popular that, in 2014, a hardcover "classic" edition was published. In April 2016, Glory over Everything: Beyond the Kitchen House will be published--a stand-alone novel, but continuing The Kitchen House story.

The Kitchen House by Kathleen Grissom (Touchstone, $16) is the story of a white indentured servant on a Virginia tobacco farm in 1791; it was published in 2010 as a paperback original, with a modest first printing. Sheanin said, "It had an Alice Walker quote and we were publishing into The Help phenomenon, but no one expected it to be the runaway bestseller that it was." It became a New York Times bestseller and book club favorite--so popular that, in 2014, a hardcover "classic" edition was published. In April 2016, Glory over Everything: Beyond the Kitchen House will be published--a stand-alone novel, but continuing The Kitchen House story. Last year, we named Fredrik Backman's A Man Called Ove (Washington Square Press, $16) one of the best books of 2014. I've given away many copies; everyone I know who's read it has been charmed. Sales took off because booksellers fell in love with it and put it into people's hands. This is a bottom-up story, according to Sheanin, rather than "a heavy-handed marketing campaign story." The novel is now in paperback, and stores are suggesting it for book clubs and "handselling like crazy." It's on several regional bestseller lists, on the national indie bestseller list, and recently landed on the Boston Globe and Los Angeles Times lists. Nonesuch Books & Cards in Maine has chosen A Man Called Ove as its book of the year, and expects to sell 1,000 copies in 2015. Sheanin and company are also big fans of Backman's second novel, My Grandmother Asked Me to Tell You She's Sorry, and are happy that to be publishing his next novel in 2016. She says, "One of the great pleasures we have watching these books take off is that booksellers are tailoring their handselling to their stores"--and doing a fine job of it. --Marilyn Dahl, editor, Shelf Awareness for Readers

Last year, we named Fredrik Backman's A Man Called Ove (Washington Square Press, $16) one of the best books of 2014. I've given away many copies; everyone I know who's read it has been charmed. Sales took off because booksellers fell in love with it and put it into people's hands. This is a bottom-up story, according to Sheanin, rather than "a heavy-handed marketing campaign story." The novel is now in paperback, and stores are suggesting it for book clubs and "handselling like crazy." It's on several regional bestseller lists, on the national indie bestseller list, and recently landed on the Boston Globe and Los Angeles Times lists. Nonesuch Books & Cards in Maine has chosen A Man Called Ove as its book of the year, and expects to sell 1,000 copies in 2015. Sheanin and company are also big fans of Backman's second novel, My Grandmother Asked Me to Tell You She's Sorry, and are happy that to be publishing his next novel in 2016. She says, "One of the great pleasures we have watching these books take off is that booksellers are tailoring their handselling to their stores"--and doing a fine job of it. --Marilyn Dahl, editor, Shelf Awareness for Readers

.jpg)

You ask a series of compelling questions in your prologue, including "Did [horses] have what scientists call 'theory of mind'--an ability that, among other things, lets us discern what others may be thinking...? Why are they willing to share their lives with us?"

You ask a series of compelling questions in your prologue, including "Did [horses] have what scientists call 'theory of mind'--an ability that, among other things, lets us discern what others may be thinking...? Why are they willing to share their lives with us?"