.jpg)

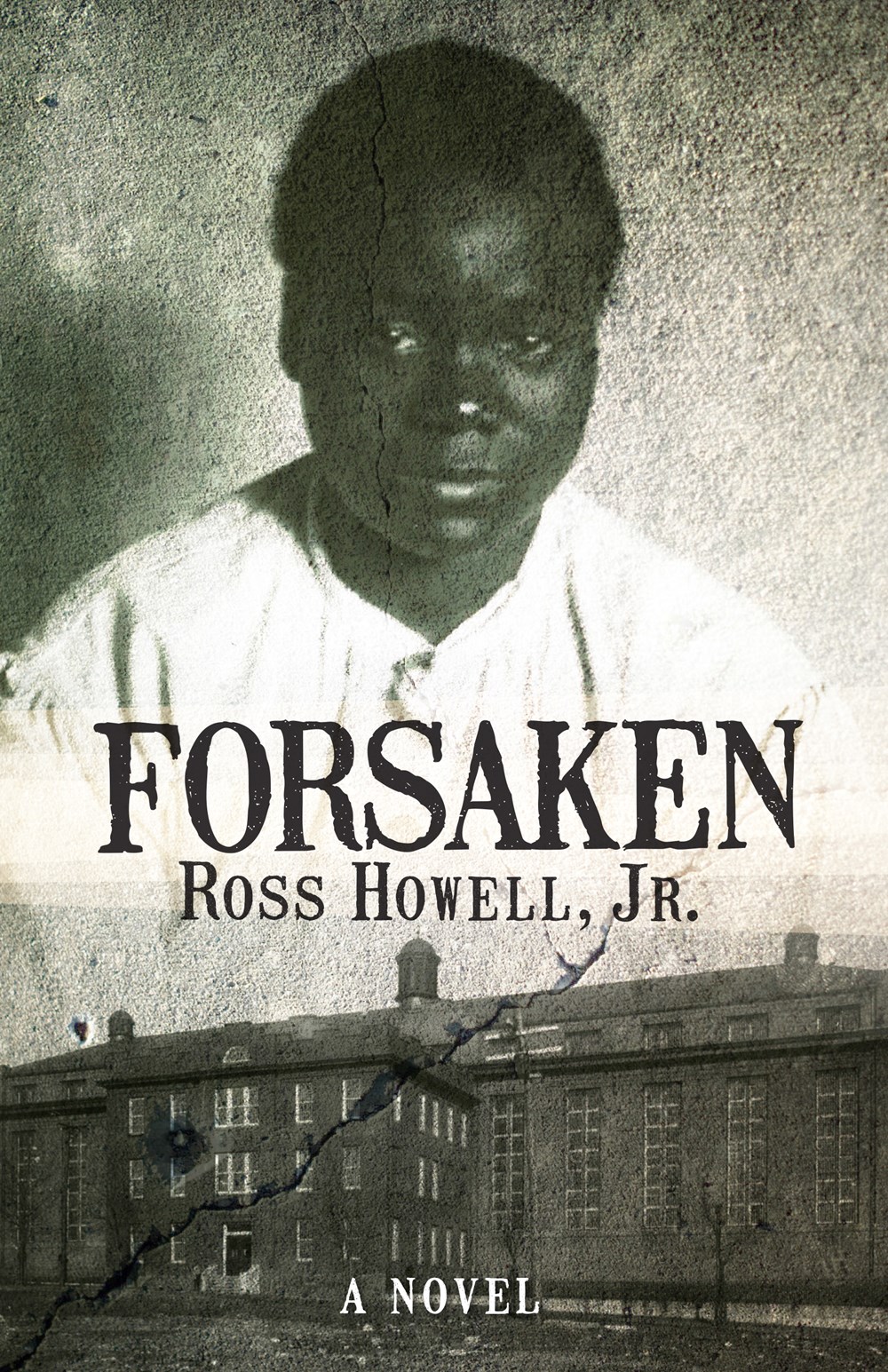

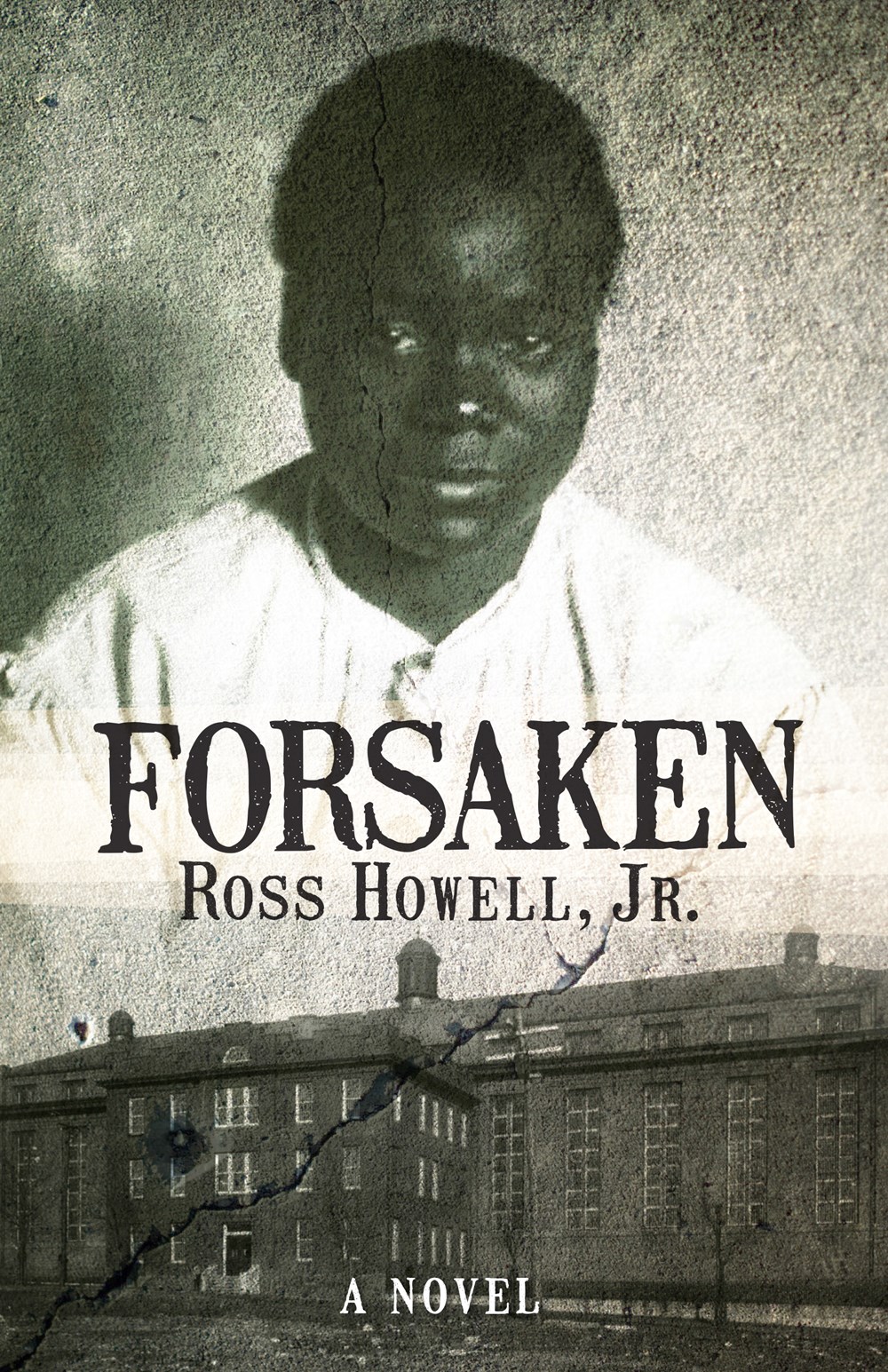

Ross Howell Jr. has taught essay writing, fiction and literature at Harvard University, Simmons College, the University of Virginia and currently at Elon University. He earned an M.F.A. at the University of Iowa Writers' Workshop. He lives in Greensboro, N.C. Forsaken (NewSouth Books, February 1) is his first novel.

Forsaken is the heartbreaking true story about the arrest, sentencing and execution of 17-year-old housemaid Virginia Christian for the murder of her employer, Ida Belote. She was found guilty of the crime in 30 minutes by an all-white jury of 12 men and sentenced to die by the electric chair.

When "Virgie" came to Mrs. Belote's house to do laundry the day of the murder, Mrs. Belote confronted her about stealing a locket. Virgie denied it and an argument ensued. Mrs. Belote struck Virgie with a piece of crockery. Virgie knocked Mrs. Belote down with a sawed-off broom handle used to prop a window. When Mrs. Belote wouldn't stop screaming, Virgie forced a dishcloth down the woman's throat with the handle, suffocating her.

A black girl had taken the life of a white woman in her home. This was one of the most reprehensible crimes imaginable in Jim Crow Virginia. The crime was a threat not only to whites in Hampton, but also to blacks, since many depended upon domestic work in white households for their livelihoods. There were calls to lynch the girl, prompting officials to move quickly to avoid mob violence.

You wrote the book from the perspective of Charlie Mears, the young reporter who covered the case for the local newspaper. Who was Charlie Mears?

Narrator Charles Mears is based on a young man from Hampton who was a freshman at William & Mary College the year before the murder. His involvement in the Temperance movement and Bible study groups, and his use of tobacco came from his college yearbook. I invented a reason for him to leave school and become the Charles Mears who was the Hampton Times-Herald reporter covering the Christian case. Mears was one of two journalists who interviewed Virgie after her conviction. She wanted to tell her story because she was upset that her attorneys had not allowed her to testify in her own defense. As for Mears's writing, we have only his newspaper articles and two letters he wrote to the governor of Virginia.

Even though the girl confessed her crime to him, Mears was the only journalist who intervened to try to save her life. The novel is really his story. What can he do in the face of evil?

How much of Virgie's story was known before you started and when did you make the decision that you wanted to write about her?

How much of Virgie's story was known before you started and when did you make the decision that you wanted to write about her?

Researching an article about the 1912 "Courthouse Massacre" in Hillsville, Va., where five people died in a shoot-out during a trial, I came across a notation that attorney George Washington Fields had referenced the event in a petition for clemency that same year. He explained to Gov. William Hodges Mann that he had not called his client to the stand for fear that a description of the murder from the lips of "an ignorant, blunt, negro girl" might result in a similar outbreak of violence in Hampton.

His client was Virginia Christian. That was the first time I'd seen her name. I learned she was the only female juvenile executed in Virginia history.

I found there was a dissertation by Derryn Moten at the University of Iowa about her case. Since I was headed to Iowa City for a Writers' Workshop reunion, I decided I'd read his dissertation while I was there. When I finished, I felt the story was so important, I needed to bring it to life.

Were there any major gaps in the story? If so, how did you deal with them?

The major gap in the story was Virgie. Little is known about her. I wanted the novel to suggest her as she was, so readers would grasp the futility and tragedy of her situation. And I was stumped by how a child never known for causing trouble could commit so brutal a murder.

In newspaper accounts, Virgie was described as "sullen," "dim-witted" and "simple-minded." While these statements reflect Jim Crow stereotypes, in fact, the girl never seemed to comprehend the enormity of what she had done. Shortly after the murder she was seen buying candy with money she had taken from Mrs. Belote's purse.

I asked a child psychologist about these descriptions and the savagery of the murder, and she said it was possible Virgie suffered from Asperger's disorder. The psychologist explained that a loud sound, like screaming, would affect an Asperger's sufferer in ways so extreme they're difficult to imagine. I suggested this disorder in drawing aspects of Virgie's character.

As a fiction author, what was it like working with historical events?

The Belote murder and Virgie's trial were front-page headlines. But just as the girl's death sentence was announced, the story disappeared. Why? Because RMS Titanic struck an iceberg and sank on her maiden voyage. But as I was studying the front page of Charlie's newspaper the day the Titanic news broke, I noticed in the right-hand column at the very bottom a two-inch announcement that the coroner's son, little George Vanderslice Jr., had died. Since the doctor was so respected in Hampton, I decided to work his son's funeral into the plot. This led me to other small events that I wove into the narrative. When we think of history, we tend to think of great events without a backdrop. And that's not the way life is.

How much or little historical documentation was there for you to work with? Did your material come from many different sources? Any surprising sources or information that you didn't expect to find?

Having read Derryn Moten's dissertation, I was able to save time locating original sources. Also, the Library of Virginia in Richmond had assembled files with court records, personal documents, letters, and newspaper articles in one location, which was tremendously time-saving. Still, the research and writing of the first draft took three years.

A great unexpected online discovery was Ajena Cason Rogers, a relative of attorney George Washington Fields. Ajena is an historical reenactor and the senior ranger at the Maggie L. Walker National Historic Site in Richmond. She was kind enough to send me a PDF of the unpublished autobiography Fields wrote late in life.

Fields is a fascinating character. I knew I had to tell his story. A slave in Hanover County, he escaped as a boy with his family to freedom in 1863. He would go on to become the first African American to receive a law degree from Cornell University, and returned to Hampton, where he ran a successful law practice. Some newspaper articles reported that he was blind; others were silent on the matter. When I read his autobiography, all Fields noted was, "In 1896 I had the great misfortune to lose my sight." I was never able to discover how.

The release of Forsaken coincides with recently inflamed racial tensions and renewed questions of social justice in the United States. What do you hope readers will take away from reading your book?

I came of age during a period of terrible racial turmoil. I attended a segregated elementary school and remember Massive Resistance [the policy to block desegregation] and the closing of schools in Prince Edward County, Va. I remember the murder of Medgar Evers. I remember the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and riots in cities throughout the country. But I also saw progress, especially with the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

When Ted Nugent recently called the president of the United States a "subhuman mongrel," he was using language straight from racial purity screeds of Virgie Christian's era. We have more young black males incarcerated than in any time in our history. We've seen videos of black people being killed by police officers with such frequency that it's mind-numbing.

The language of white supremacy hate groups in this country comes as no surprise. But the rhetoric of some politicians does. Virgie Christian's life and death were shaped by the distrust and hate of one race for another. I saw that distrust and hate as a young man. And now, a full century after her death, I see hate and distrust growing.

I hope readers take away from this novel empathy, hope and the resolve to honor human dignity. --Jarret Middleton

Ross Howell Jr.: Guilt and Hatred Under Jim Crow

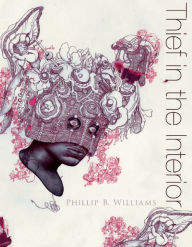

A gay black boy's dismembered body forms the centerpiece, and Williams twists tactile, electric lines about brutal hate crimes into ornate and compelling verse: "the boy's first word for pain/ is the light's/ new word for home," indicting the violence black bodies are subjected to. Yet as unflinching as his gaze is toward human cruelties, Williams also adorns his writing with moments of tenderness: "O darling, the moon did not disrobe you./ You fell asleep that way, nude."

A gay black boy's dismembered body forms the centerpiece, and Williams twists tactile, electric lines about brutal hate crimes into ornate and compelling verse: "the boy's first word for pain/ is the light's/ new word for home," indicting the violence black bodies are subjected to. Yet as unflinching as his gaze is toward human cruelties, Williams also adorns his writing with moments of tenderness: "O darling, the moon did not disrobe you./ You fell asleep that way, nude."

.jpg)

How much of Virgie's story was known before you started and when did you make the decision that you wanted to write about her?

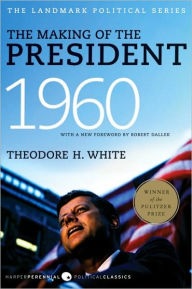

How much of Virgie's story was known before you started and when did you make the decision that you wanted to write about her?  The Making of the President 1960 by Theodore H. White is a pivotal entry in the annals of American political reporting. It chronicles the 1960 election of John F. Kennedy, through his primary battle against Hubert Humphrey and Stuart Symington, convention challenges from Adlai Stevenson and Lyndon B. Johnson (who became his running mate) to the general election against Richard Nixon. White's narrative nonfiction style and penetrating insights into political trends made The Making of the President 1960 a bestseller and won it the 1962 Pulitzer Prize for General Non-Fiction.

The Making of the President 1960 by Theodore H. White is a pivotal entry in the annals of American political reporting. It chronicles the 1960 election of John F. Kennedy, through his primary battle against Hubert Humphrey and Stuart Symington, convention challenges from Adlai Stevenson and Lyndon B. Johnson (who became his running mate) to the general election against Richard Nixon. White's narrative nonfiction style and penetrating insights into political trends made The Making of the President 1960 a bestseller and won it the 1962 Pulitzer Prize for General Non-Fiction.