|

| photo: Barbara Sullivan |

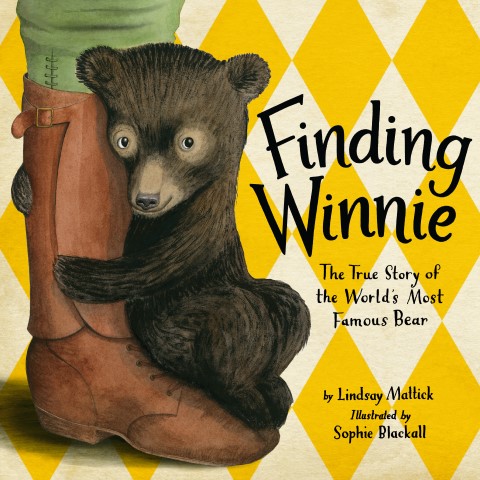

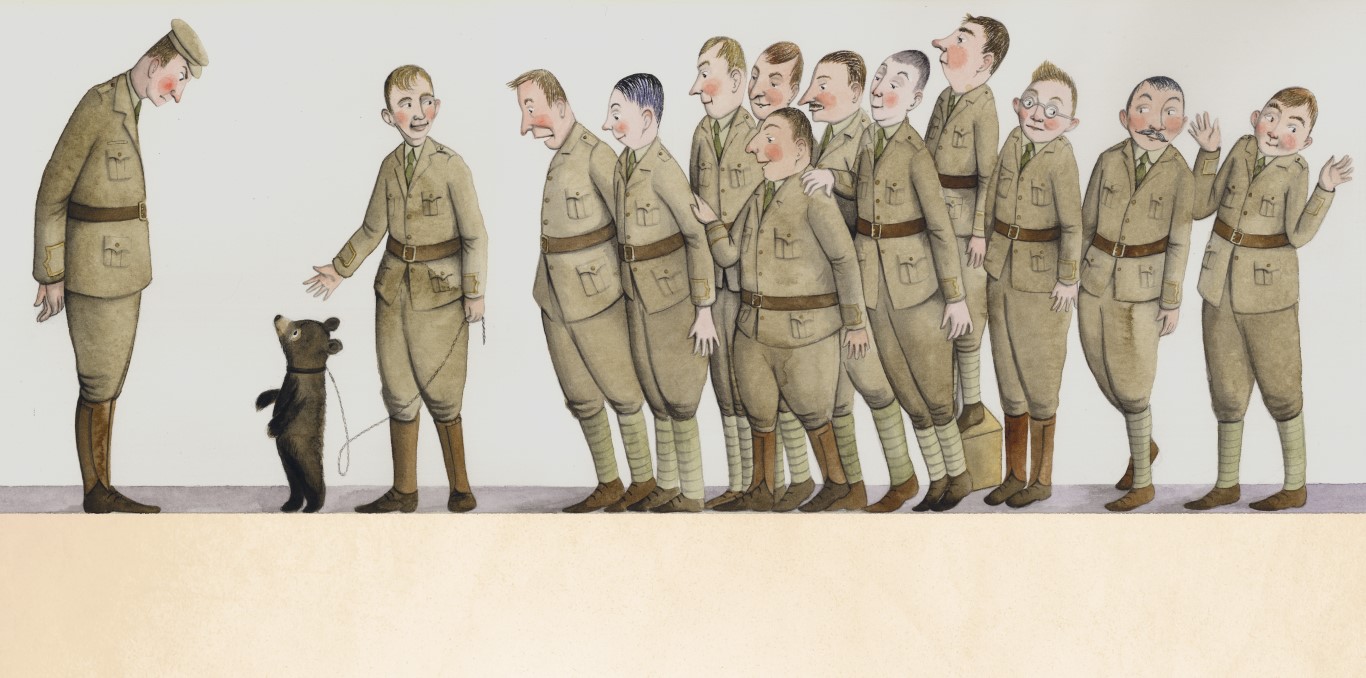

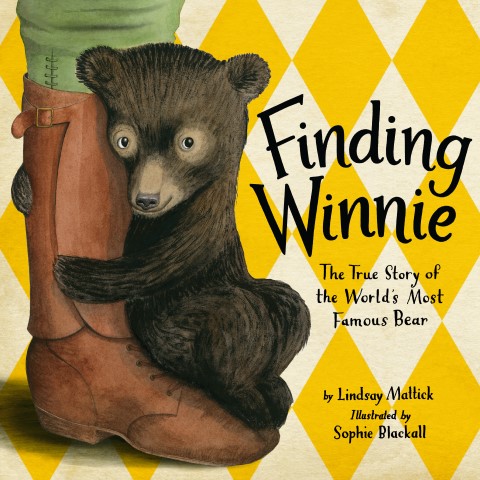

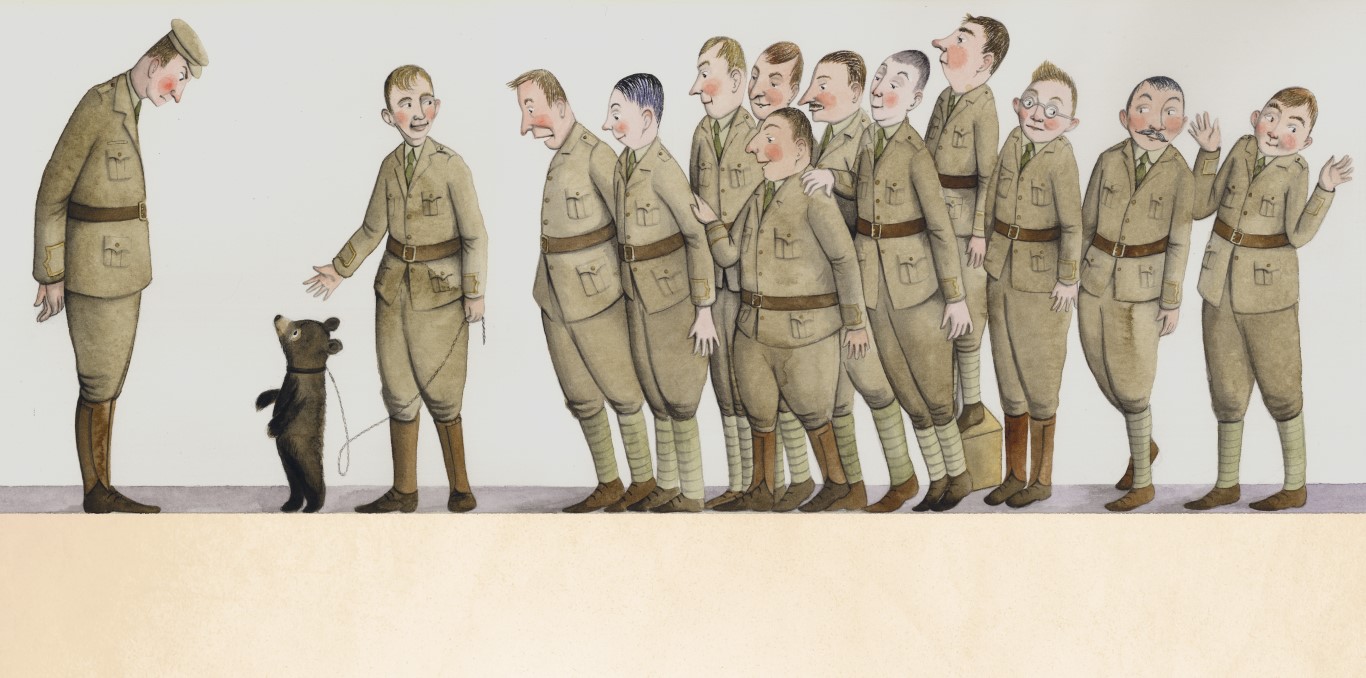

Australia-born artist Sophie Blackall has illustrated more than 30 books for children, including the award-winning Ruby's Wish and the popular Ivy and Bean series. On January 11, she was awarded the 2016 Randolph Caldecott Medal for her splendid artwork in Finding Winnie: The True Story of the World's Most Famous Bear (Little, Brown). Before Winnie-the-Pooh, Winnie was a real-life black bear, rescued by a soft-hearted Canadian soldier named Harry Colebourn on his way to England during World War I to be a veterinarian. This winning picture book, written by Colebourn's great-granddaughter Lindsay Mattick, tells the story of how that bear ended up at the London Zoo and became the inspiration for A.A. Milne's beloved Winnie-the-Pooh. Here, Blackall answers some questions for Shelf Awareness from her home in Brooklyn, N.Y.

Did you grow up reading Winnie-the-Pooh?

Winnie-the-Pooh was the first book I bought with my own money. It was a battered 1950 edition in my mother's antique shop, and after school I would curl up under an old oak dining table and read it over and over. I used to try to hide it in the shop so nobody would buy it. Eventually my mother sold it to me for a dollar. I polished the steps to earn the money. I had never read a book like it. A book with interjections and digressions and ponderings. One that meandered and backtracked, that bounced and hummed, that drew you in so close that you felt you were in the very forest itself, and simultaneously allowed you to step back and see the actual form of a book. With characters so endearing they became your lifelong friends.

It was E.H. Shepard's drawings that first made me want to be an illustrator. So, when editor Susan Rich sent me the manuscript for Finding Winnie, I felt as though everything had been leading me to this book.

Finding Winnie explains the origin of the "Winnie" part of the Winnie-the-Pooh--from the Canadian soldier's hometown of Winnipeg--but not the "Pooh" part.

Finding Winnie explains the origin of the "Winnie" part of the Winnie-the-Pooh--from the Canadian soldier's hometown of Winnipeg--but not the "Pooh" part.

Pooh is the name Christopher Robin gives to a swan he feeds in the mornings! "This is a very fine name for a swan, because, if you call him and he doesn't come (which is a thing swans are good at), then you can pretend that you were just saying 'Pooh!' to show him how little you wanted him." (from A.A. Milne's When We Were Very Young)

Did you draw when you were a child?

Constantly. On my walk home from elementary school. I would pass the butcher shop and beg for some paper. The butcher would roll me up a few sheets and slice me a piece of mortadella into the bargain. I've been fond of butchers ever since. I wish I could thank him.

Do you prefer drawing animals to people?

I like drawing both, but I confess I almost always want to put clothes on animals. It was all I could do not to give Winnie a scarf or a fetching hat.

The book says your medium is "Chinese ink and watercolor on hot-press paper." Tell us about that.

I use Chinese ink to paint the gray tones, and watercolor washes over the top. I use Schmincke watercolors, in a tin set my father gave me when I was 15. After 35 books, I've had to replace a few of the colors, but they last such a long time.

The cover of Finding Winnie is so clever, showing one leg on the front cover and one leg on the back to make sort of a hybrid person based on the two sections of the book. How did that cover design evolve?

The cover of Finding Winnie is so clever, showing one leg on the front cover and one leg on the back to make sort of a hybrid person based on the two sections of the book. How did that cover design evolve?

We must have tried at least a dozen different ideas for the cover. We knew we wanted the front to show Harry and Winnie and the back to show Christopher Robin and Winnie-the-Pooh. I had drawn both pairs full figure and it took a while to work out that I needed to zoom in and just show the legs.

I love the book cover underneath the jacket, with the silhouetted soldiers marching, led by the bear. Are there any more secret things hidden inside Finding Winnie?

This inner cover is one of my favorite things about the book. It's an homage to E.H. Shepard's endpapers in my old edition of Winnie-the-Pooh. I tucked quite a few secrets and jokes into the book, one of the many fun things about being an illustrator. There's a message to be decoded in the signal flags, and several details to be discovered in the map of the zoo. Careful readers will notice the owl in Cole's bedroom. [In Finding Winnie, Cole is the little boy listening to his mother's story as it unfolds.]

The story starts in 1914 Canada, then moves to England when Harry Colebourn goes off to war. What sort of research did you do to make sure the illustrations were historically accurate?

The story starts in 1914 Canada, then moves to England when Harry Colebourn goes off to war. What sort of research did you do to make sure the illustrations were historically accurate?

I visited the archives of the London Zoo to see photographs and news clippings and the ledger in which Winnie's arrival was recorded by the zookeeper in exquisite copperplate. I went to the Imperial War Museum and read soldiers' diaries and I traveled the road Harry and Winnie took to the city, past Stonehenge.

Back at my desk, several things had me tied up in knots: the bird's-eye view of the zoo, which involved researching period photographs of every building and cross-referencing those with a footprint map I had from 1913; getting the train right (luckily I share a studio with Brian Floca who offered encouragement--I think I can, I think I can--and access to his library of train books); figuring out the parade of ships with the only existing color reference being a painting called Canada's Answer--an impressionistic interpretation of the crossing made some years after the event--and learning signal flags. In addition to my own research, I was so fortunate to have access to Lindsay Mattick's family documents and photographs, many of which appear in the album at the end of the book.

At one point, the World War I part of the story ends, and the focus shifts to Christopher Robin Milne, A.A. Milne's son, the boy who sees Winnie at the London Zoo. Tell us about that visual shift.

Hearing that Harry leaves Winnie at the zoo, the little boy, Cole, is devastated. His mother explains, tenderly, that sometimes you have to let one story end so the next one can begin. "How do you know when that will happen?" he asks. "You don't," she says. "Which is why you should always carry on." This makes me choke up every time.

We turn the page to see Christopher Robin with his bear and it feels like a new beginning, "Once upon a time..." I think this idea is quite profound. It's how, as human beings, we deal with loss and change. And it ties these momentous events in our lives back to storytelling. Every family is full of stories and we pass them down from generation to generation. The wonderful thing about a book is that when we get to the end, we can begin again at the beginning.

You share an art studio with a handful of luminaries from the children's book world--you mention Brian Floca, Eddie Hemingway, John Bemelmans Marciano and Sergio Ruzzier. It sounds positively dreamy.

My studio mates are my second family, my best friends. I have learned so much from working in their company. We share reference books and industry gossip and lunch and I can't imagine going back to working in isolation. In fact, we are planning a retirement home for illustrators. We'll all have arthritis by then so we'll play Pictionary with our feet.

What are you working on now?

I'm working on a new series with my studio mate John Bemelmans Marciano, called the Witches of Benevento, which comes out this April with Viking, and a picture book with Chronicle, which is immense and immensely exciting.

Anything else you'd like to tell the readers of Shelf Awareness?

Finding Winnie is about a spur-of-the-moment act of kindness. It's about ordinary people who do extraordinary things. It's about the connections we make throughout our lives and the possibility that any of those might prove to be profound. It's about stories passed down to us through generations and the stories we share with children and the stories we leave behind.

This story belongs to Captain Harry Colebourn and his great-granddaughter Lindsay, and her son Cole. It belongs to everyone who ever loved Winnie-the-Pooh, and it belongs to every child who wonders what he or she may do in their lifetime, what small thing might change the world. --Karin Snelson, children's & YA editor, Shelf Awareness

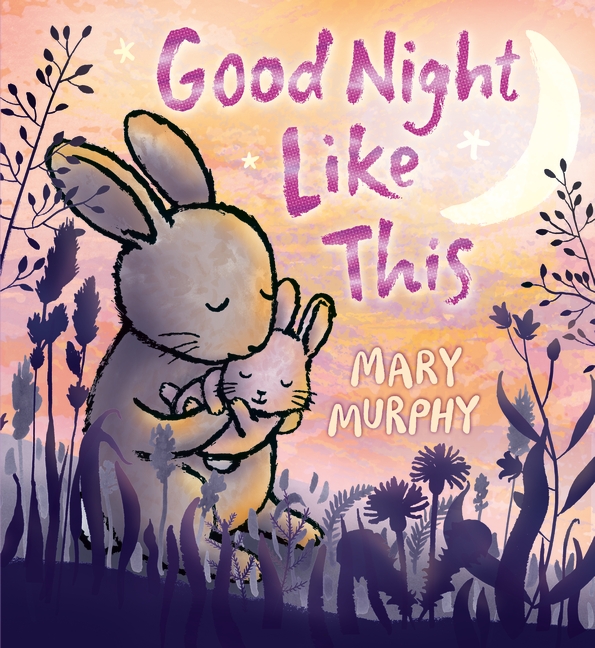

Lilac skies are the twilight backdrop for the adorable sleepy animal babies in Good Night Like This (Candlewick) by Mary Murphy (Say Hello Like This!). The lovely lullaby begins with a rabbit cradling a bunny: "Yawny and dozy, twitchy and cozy. Good night, rabbits. Sleep tight...." Turn the cut-away page to find the words "like this," the book's refrain. As children bid goodnight to "flitty and shiny" fireflies, bears and squirrels, they may just follow suit.

Lilac skies are the twilight backdrop for the adorable sleepy animal babies in Good Night Like This (Candlewick) by Mary Murphy (Say Hello Like This!). The lovely lullaby begins with a rabbit cradling a bunny: "Yawny and dozy, twitchy and cozy. Good night, rabbits. Sleep tight...." Turn the cut-away page to find the words "like this," the book's refrain. As children bid goodnight to "flitty and shiny" fireflies, bears and squirrels, they may just follow suit.

Finding Winnie explains the origin of the "Winnie" part of the Winnie-the-Pooh--from the Canadian soldier's hometown of Winnipeg--but not the "Pooh" part.

Finding Winnie explains the origin of the "Winnie" part of the Winnie-the-Pooh--from the Canadian soldier's hometown of Winnipeg--but not the "Pooh" part.  The cover of Finding Winnie is so clever, showing one leg on the front cover and one leg on the back to make sort of a hybrid person based on the two sections of the book. How did that cover design evolve?

The cover of Finding Winnie is so clever, showing one leg on the front cover and one leg on the back to make sort of a hybrid person based on the two sections of the book. How did that cover design evolve?  The story starts in 1914 Canada, then moves to England when Harry Colebourn goes off to war. What sort of research did you do to make sure the illustrations were historically accurate?

The story starts in 1914 Canada, then moves to England when Harry Colebourn goes off to war. What sort of research did you do to make sure the illustrations were historically accurate?  Rudyard Kipling's The Jungle Book is coming back to the big screen. Twice. The first adaptation, from Disney, comes out April 15, 2016, with Jon Favreau (Elf; Iron Man) directing an A-list voice cast: Scarlett Johansson as the snake Kaa, Idris Elba as the tiger Shere Khan, Lupita Nyong'o as the wolf Raksha, Christopher Walken as the ape King Louie, Bill Murray as the bear Baloo and Ben Kingsley as the panther Bagheera. The Warner Brothers offering, scheduled for October 6, 2017, with a titular twist (Jungle Book: Origins), is the directorial debut of motion capture master Andy Serkis, who will also voice Baloo, alongside Christian Bale as Bagheera, Cate Blanchett as Kaa and Benedict Cumberbatch as Shere Khan. After Disney's beloved 1967 animated film, these movies have big prints to fill.

Rudyard Kipling's The Jungle Book is coming back to the big screen. Twice. The first adaptation, from Disney, comes out April 15, 2016, with Jon Favreau (Elf; Iron Man) directing an A-list voice cast: Scarlett Johansson as the snake Kaa, Idris Elba as the tiger Shere Khan, Lupita Nyong'o as the wolf Raksha, Christopher Walken as the ape King Louie, Bill Murray as the bear Baloo and Ben Kingsley as the panther Bagheera. The Warner Brothers offering, scheduled for October 6, 2017, with a titular twist (Jungle Book: Origins), is the directorial debut of motion capture master Andy Serkis, who will also voice Baloo, alongside Christian Bale as Bagheera, Cate Blanchett as Kaa and Benedict Cumberbatch as Shere Khan. After Disney's beloved 1967 animated film, these movies have big prints to fill.