.jpg) G. Neri was so eager to learn about the real-life childhood friendship between Harper Lee, author of To Kill a Mockingbird, and Truman Capote, author of In Cold Blood, he couldn't wait to write the story. Here, Neri answers some questions for Shelf Awareness about his new middle-grade novel Tru & Nelle (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt), set in 1930s Monroeville, Ala. Neri has written many children's books, including Yummy: The Last Days of a Southside Shorty, a Coretta Scott King Author Honor winner; Knockout Games; Hello, I'm Johnny Cash and Ghetto Cowboy. He lives in Florida with his wife and daughter.

G. Neri was so eager to learn about the real-life childhood friendship between Harper Lee, author of To Kill a Mockingbird, and Truman Capote, author of In Cold Blood, he couldn't wait to write the story. Here, Neri answers some questions for Shelf Awareness about his new middle-grade novel Tru & Nelle (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt), set in 1930s Monroeville, Ala. Neri has written many children's books, including Yummy: The Last Days of a Southside Shorty, a Coretta Scott King Author Honor winner; Knockout Games; Hello, I'm Johnny Cash and Ghetto Cowboy. He lives in Florida with his wife and daughter.

How did you decide to write about the historic childhood friendship between Truman Capote (Tru) and Harper Lee (known as Nelle)?

When actor Philip Seymour Hoffman passed away in February 2014, I began to revisit his movies. The first film I watched was his Oscar-winning portrayal of Truman in Capote. There was Truman with Harper Lee (!), trying to get to the bottom of a small-town crime in Kansas. From there, I vaguely remembered that they had grown up as next-door neighbors when they were children in Alabama, and as soon as the film was over, I started digging into that because I was curious. What I found were a series of outrageously funny and poignant stories of their childhood adventures that I had never heard of before. They read like fiction to me, but nobody had really written for kids about these two misfits. I wanted to see that book so bad, I started writing it in April and I had a draft by June. The rest was just tightening and reworking it, but the basics were all there.

This notion of two of our most beloved authors growing up together as kids in the middle of nowhere is what first grabbed my imagination. What kept me there for the long haul was Nelle's quiet humanity and stubborn refusal to accept things as they were. She was the heart and soul behind To Kill a Mockingbird and expressed what many suspected was wrong about Jim Crow but were too afraid to acknowledge publicly. She wrote about these things when few dared, perhaps a consequence of her young age and stubborn disposition. She had gumption and gall and a healthy dose of honesty that soon turned into the most important and beloved American novel, arguably ever.

What sort of research did you do?

I read everything I could about their friendship. The key books were Marianne M. Moates's retelling of the life of Truman's cousin Jennings Faulk Carter, who was the third wheel in this friendship. His recollections of their childhood adventures were wonderful--full of life and mischief. Truman's aunt Tiny wrote a rather scandalous version of Truman's life, which, in the great storytelling tradition of the South, was highly embellished (but very entertaining). Then it was collecting as many first-hand accounts of those years as I could and piecing it all together into a single narrative.

Did you ever meet Harper Lee?

Regrettably, I never had the opportunity to meet Harper Lee in person. She was too deaf and blind, in her words, to talk to anyone. But I did manage to spend many, many months with her younger self, Nelle, while writing this novel.

.jpg) Do you think you captured the spirit of the young Harper Lee?

Do you think you captured the spirit of the young Harper Lee?

I got to know her quite well. I walked in her shoes, witnessed the events of her childhood in the early years of the Great Depression in the Jim Crow-era Deep South. Felt her words tumbling around my head and back out onto the page. True, it was a slightly fictional version of her. But I was after the poetic truth. I think I found it, or as much as one can find out from a person living in your head.

What was she like as a child?

The two qualities that drew me to young Nelle, the Nelle of Scout's age, was that she was an outsider and a misfit. As such, she seemed to have an innate sense of justice. She was an observer, even at that age, and could see the difference between how black folks were treated, even if she couldn't quite understand why. Through her father, who was the model for Atticus Finch, she saw how segregation formed the spoken and unspoken laws around her.

She had her own way about her and wasn't afraid to be a tomboy, even if it rubbed others the wrong way. As a kid, she was rough and tumble, and could beat the steam out of any boy who didn't care for her "unladylike" manner. She never wore dresses, only overalls with (mostly) no shoes. Girls didn't know how to deal with her, so they often kept her at arm's length. She called her father by his first name, not "daddy" or "sir" like most girls would. She also loved to read.

How did Harper Lee meet Truman Capote?

Truman Capote was an odd, undersized boy in a prissy suit who moved in next door to her. He, too, was an outsider and a misfit. He looked like little Lord Fauntleroy, refined and well spoken, in a time when most of the poor rural kids went to school barefoot and in homemade clothes. He was bullied mercilessly by the other boys. Nelle hated bullies, even though she was often accused of that herself. She stood up for the underdog Truman and didn't care who knew it.

Why do you think they were such good friends?

These two outsiders bonded over a mutual love of detective mysteries. Both had active imaginations but Truman had the gift of gab, mostly as a survival mechanism. He loved to take the day's events and turn them into outlandish stories. Nelle loved to listen to these exaggerated versions of their humdrum lives in which they were often the heroes. Together in their vivid imaginations, they pretended to be Sherlock Holmes and Watson, solving small-town mysteries in boring old Monroeville, Ala.

Tell us about your own experience with To Kill a Mockingbird.

As an author of middle grade and young adult fiction, I have visited a lot of urban schools around the country with diverse populations and wildly different reading habits. There are very few books that truly cross over to all students in the U.S. For many, To Kill a Mockingbird is their first exposure to exploring race and racism in this country. For me, it was the first "serious" book I read. It has become common ground, meaning, no matter where you are, from Alabama to Alaska, or what the color of your skin may be, you will have this shared experience, by the time you are in high school. In this day and age, that is an increasingly rare thing to find.

How are kids today reacting to To Kill a Mockingbird?

In the age of Trayvon and Ferguson, many will interpret the ideas of this book differently. To some, Mockingbird might seem tame in comparison to today's events. But as a vehicle for fostering dialogue and sharing different points of view on race through the eyes of eighth and ninth graders, it has managed the unimaginable feat of staying relevant for 55 years.

Any thoughts on Harper Lee's Go Set a Watchman?

When Ms. Lee failed to produce a second novel, many felt she was the voice of a generation that refused to speak anymore. When Go Set a Watchman did appear, many complained about what that voice had to say. One thing is for certain: her place in the civil rights movement cannot be denied. The injustice that we hoped would be befitting of a historical novel is not some quaint notion from the past. Mockingbird is, unfortunately, as timely now as it was then.

What are you working on now?

I have two books that are finished and being illustrated right now. One is a graphic novel about my cousin, the horse thief, who is kind of a modern-day outlaw and horse advocate hero, called Grand Theft Horse. The other is a picture book about the childhood friendship between Paul Simon and Art Garfunkel. It's really a story about the birth of rock 'n' roll and the surprising connection these two legends had to that cultural shift. On top of that, I am collaborating on something I've never attempted before, a kind of urban dystopian-horror novel.

G. Neri: Walking in Harper Lee's Shoes

Cat Winters (In the Shadow of Blackbirds) mines Shakespeare's Hamlet for the plot and characters in her excellent, spellbinding novel set in 1923 Oregon, The Steep and Thorny Way (Amulet). Hanalee Denney is the daughter of a white woman and an African American man. He may have been murdered, and is definitely now a ghost, sticking around to warn Hanalee about those who wish to harm her. As hate and intolerance boil over in the Klan-influenced town, Hanalee suspects foul play in her father's death, even on the part of her stepfather. Her search for answers makes for a powerful, painful story of love and courage.

Cat Winters (In the Shadow of Blackbirds) mines Shakespeare's Hamlet for the plot and characters in her excellent, spellbinding novel set in 1923 Oregon, The Steep and Thorny Way (Amulet). Hanalee Denney is the daughter of a white woman and an African American man. He may have been murdered, and is definitely now a ghost, sticking around to warn Hanalee about those who wish to harm her. As hate and intolerance boil over in the Klan-influenced town, Hanalee suspects foul play in her father's death, even on the part of her stepfather. Her search for answers makes for a powerful, painful story of love and courage.

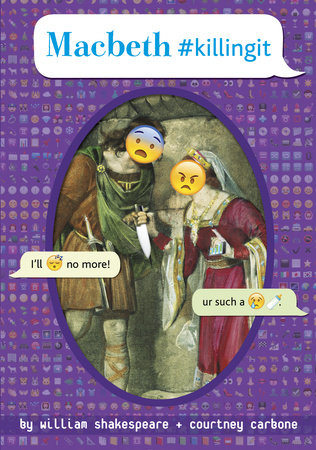

Is brevity really the soul of wit? The OMG Shakespeare series (Random House), including Macbeth #killingit by Courtney Carbone, takes classic Shakespearean plays and retells them with emoji-riddled texts. Example: "Macbeth: UGH! MALCOLM is Prince of Cumberland now? Well, that sux. It's gonna be a lot harder to become [crown emoji]. #AlwaysTheThane [sad-face emoticon]." There's "The 411" in the back, defining YOLO (you only live once), NBD (No Big Deal) and the like. A fun comparison exercise for cultural anthropologists.

Is brevity really the soul of wit? The OMG Shakespeare series (Random House), including Macbeth #killingit by Courtney Carbone, takes classic Shakespearean plays and retells them with emoji-riddled texts. Example: "Macbeth: UGH! MALCOLM is Prince of Cumberland now? Well, that sux. It's gonna be a lot harder to become [crown emoji]. #AlwaysTheThane [sad-face emoticon]." There's "The 411" in the back, defining YOLO (you only live once), NBD (No Big Deal) and the like. A fun comparison exercise for cultural anthropologists.

.jpg) G. Neri

G. Neri.jpg) Do you think you captured the spirit of the young Harper Lee?

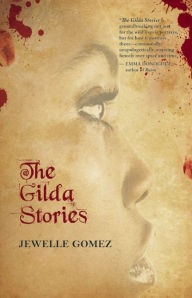

Do you think you captured the spirit of the young Harper Lee? After a runaway slave girl in 1850s Louisiana kills a bounty hunter in self defense, she takes shelter with two women who run a brothel. These women happen to be vampires, and induct the girl, Gilda, into an eternal life of one who "shares the blood." The Gilda Stories by Jewelle Gomez follows the next 200 years of Gilda's life, from California in 1890, Missouri in 1921, Massachusetts in 1955, New York in 1981, New Hampshire in 2020, all the way up to 2050. Gilda's many lives are defined by the quest to understand her sexual and racial identities, and to find a place for her as the ultimate outsider in a constantly changing world.

After a runaway slave girl in 1850s Louisiana kills a bounty hunter in self defense, she takes shelter with two women who run a brothel. These women happen to be vampires, and induct the girl, Gilda, into an eternal life of one who "shares the blood." The Gilda Stories by Jewelle Gomez follows the next 200 years of Gilda's life, from California in 1890, Missouri in 1921, Massachusetts in 1955, New York in 1981, New Hampshire in 2020, all the way up to 2050. Gilda's many lives are defined by the quest to understand her sexual and racial identities, and to find a place for her as the ultimate outsider in a constantly changing world.