British children's book author Roald Dahl was an expert at the one-two punch of sentiment and scorn. He could never resist a final twist:

I had a little nut-tree,

Nothing would it bear.

I searched in all its branches,

But not a nut was there.

"Oh, little tree," I begged,

"Give me just a few."

The little tree looked down at me

And whispered, "Nuts to you."

--"A Little Nut-Tree" from Rhyme Stew (1989)

This is a clever spoof of Mother Goose's classic "I Had a Little Nut Tree," but could it also be a wry response to Shel Silverstein's The Giving Tree (1964)? Either way, the small poem is vintage Dahl in that just as you're about to finish it, it flips around to bite you.

|

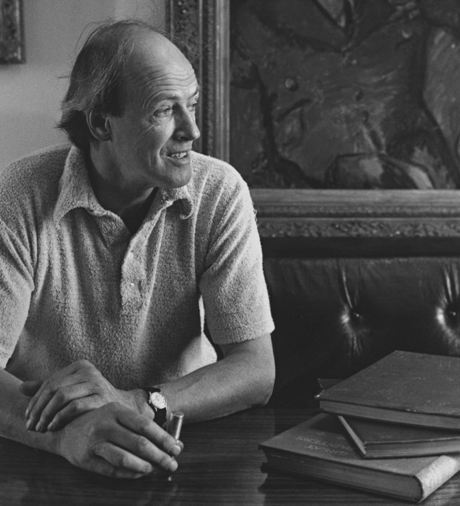

| photo: © RDNL 2016 |

Roald Dahl was a natural poet, though he's best known for his popular children's novels, including James and the Giant Peach (1961), Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (1964), The Witches (1983) and Matilda (1988). His books, translated into more than 58 languages, have sold 200 million copies, and many of them have been adapted for the silver screen, including Steven Spielberg's adaptation of The BFG (short for the "Big Friendly Giant") premiering July 1, 2016. The Independent once confidently pronounced Roald Dahl "without question the most successful children's writer in the world." Few would argue that Dahl knew instinctively what children liked in a story: loads of action, a strong sense of right and wrong, clearly identifiable good guys and bad guys, a dash of magic, dark humor, sweet revenge, some gas-passing and a splash of violence.

Dahl also reveled in wordplay, and poetry bubbled up as rhythmic songs and chants in many of his novels, as well as in his books of verse--Revolting Rhymes (1982), Dirty Beasts (1983) and Rhyme Stew. "He had a wonderful ear for rhyme," said Stephen Roxburgh, his longtime editor at Farrar, Straus & Giroux. "He was one of those poets--Ogden Nash and Shel Silverstein were two others--who could write light verse and avoid cliché."

As a child, Dahl was more interested in photography, cricket, or childish pranks than in words. He was born in Wales on September 13, 1916, to Norwegian parents. Dahl's later childhood straddled two very different worlds--long and glorious summers in Norway, and the rigors of English boarding schools during the academic year. Dahl's memories of sadistic, cane-happy headmasters would infuse his work for the rest of his days. Adults are often frightening, repulsive, even filthy creatures in his fantastical stories. Both the noblest and nastiest extremes of humankind are represented, often with the noblest (a child), destroying the nastiest (an adult), in a ghastly act of revenge for some injustice. In a jolly-metered poem called "Mister Unsworth," first published in Vile Verses (2005), he paints a dark picture of a cruel teacher:

As a child, Dahl was more interested in photography, cricket, or childish pranks than in words. He was born in Wales on September 13, 1916, to Norwegian parents. Dahl's later childhood straddled two very different worlds--long and glorious summers in Norway, and the rigors of English boarding schools during the academic year. Dahl's memories of sadistic, cane-happy headmasters would infuse his work for the rest of his days. Adults are often frightening, repulsive, even filthy creatures in his fantastical stories. Both the noblest and nastiest extremes of humankind are represented, often with the noblest (a child), destroying the nastiest (an adult), in a ghastly act of revenge for some injustice. In a jolly-metered poem called "Mister Unsworth," first published in Vile Verses (2005), he paints a dark picture of a cruel teacher:

...He'd twist and twist and twist your ear and twist it more and more,

Until at last the ear came off and landed on the floor.

Our class was full of one-eared boys, I'm certain there were eight,

Who'd had them twisted off because they didn't know a date.

So let us now praise teachers who today are all so fine

And yours in particular is totally divine.

Dahl first wrote for adults, but ultimately found his best audience when he had children of his own to regale with stories. His daughter Ophelia, one of five children Dahl had with American actress Patricia Neal, recalled that the funny, sometimes morbid vignettes that her father told her at bedtime were the seeds of his most popular children's novels. Editor Roxburgh, who became a good friend of the family, said that Dahl was a different person around children than he was around adult colleagues or friends. "He would play the BFG," said Roxburgh. "The sentimentality in his children's work is pure, if you can ever say Dahl is pure. I think he drew heavily from his idyllic early childhood. And he loved children. That's the source of his great works."

Dahl first wrote for adults, but ultimately found his best audience when he had children of his own to regale with stories. His daughter Ophelia, one of five children Dahl had with American actress Patricia Neal, recalled that the funny, sometimes morbid vignettes that her father told her at bedtime were the seeds of his most popular children's novels. Editor Roxburgh, who became a good friend of the family, said that Dahl was a different person around children than he was around adult colleagues or friends. "He would play the BFG," said Roxburgh. "The sentimentality in his children's work is pure, if you can ever say Dahl is pure. I think he drew heavily from his idyllic early childhood. And he loved children. That's the source of his great works."

By 1960, Dahl was entrenched in his career as a children's book author. Though he spent years commuting across the Atlantic, Dahl wrote many of his beloved stories in England, in a small, dilapidated hut in the garden near Gipsy House, his family home in Great Missenden, Buckinghamshire. The writing hut, cozy for the nearly 6"6' author it accommodated, was adorned with strewn-about oddities, such as one of his femur bones (later replaced) and a heavy ball of silver paper rolled from chocolate-bar wrappers. Dahl's lifelong love of nature, stemming from his Norwegian holidays, could be indulged here in this modest retreat, surrounded by fruit trees in the English countryside.

It was in this same hut that James and the Giant Peach, the story of an expanding peach that ultimately squashes a pair of horrid spinster aunts, was birthed. Revenge is literally sweet, and a little sticky, in the limerick-like poem "The Centipede's Song of Aunt Sponge and Aunt Spiker." James and the Giant Peach met with mixed reviews upon its publication in the U.S. in 1961. Some critics, according to Dahl's biographer Jeremy Treglown, "were particularly enthusiastic about the jaunty poems, part Edward Lear, part Hilaire Belloc...." But if you were a critic who thought death by peach seemed overly bizarre or brutal, you were, in Dahl's mind, probably a grown-up.

.jpg) In Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, Fantastic Mr. Fox (1970) and Matilda, Dahl persisted in playing with words. In fact, it is difficult to discuss Dahl as a poet separately from Dahl as a storyteller; his poems are stories, and his stories, however "no-frills," are poetic. The BFG (1982), for instance, is a charming novel about a big friendly giant who blows dreams into the bedrooms of sleeping children at night and speaks an endearingly mangled language all his own. When the young orphan Sophie, whom he kidnaps, tells the giant she thinks his garbled English (his "terrible wigglish") is beautiful, the giant is overcome: "How whoopsy-splunkers! How absolutely squiffling! I is all of a stutter."

In Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, Fantastic Mr. Fox (1970) and Matilda, Dahl persisted in playing with words. In fact, it is difficult to discuss Dahl as a poet separately from Dahl as a storyteller; his poems are stories, and his stories, however "no-frills," are poetic. The BFG (1982), for instance, is a charming novel about a big friendly giant who blows dreams into the bedrooms of sleeping children at night and speaks an endearingly mangled language all his own. When the young orphan Sophie, whom he kidnaps, tells the giant she thinks his garbled English (his "terrible wigglish") is beautiful, the giant is overcome: "How whoopsy-splunkers! How absolutely squiffling! I is all of a stutter."

Dahl's fondness for the story-poem is evident in Revolting Rhymes as well. This small book, illustrated by Quentin Blake, consists of comical and gruesome retellings, in sing-song rhyme, of six already quite gritty folktales including "Cinderella" (whose stepsisters get decapitated and who ends up marrying a jam-maker) and "Goldilocks and the Three Bears" with its trespassing, porridge-stealing star: "It is a mystery to me/ Why loving parents cannot see/ That this is actually a book/ About a brazen little crook."

Dirty Beasts is also crawling with story-poems about vigilante justice, Dahl-style. When the pig eats the farmer before the farmer eats him in "The Pig," readers can imagine Dahl's boarding-school fantasies at work. Many of the poems seem bent on frightening the wits out of children at bedtime. Three-quarters into a poem about a crocodile who likes to eat children, the narrator whispers, "Shh! Listen! What is that I hear/ Gallumphing [sic] softly up the stair?/ Go lock the door and fetch my gun!/ Go on, child, hurry! Quickly, run!"

Dirty Beasts is also crawling with story-poems about vigilante justice, Dahl-style. When the pig eats the farmer before the farmer eats him in "The Pig," readers can imagine Dahl's boarding-school fantasies at work. Many of the poems seem bent on frightening the wits out of children at bedtime. Three-quarters into a poem about a crocodile who likes to eat children, the narrator whispers, "Shh! Listen! What is that I hear/ Gallumphing [sic] softly up the stair?/ Go lock the door and fetch my gun!/ Go on, child, hurry! Quickly, run!"

Dahl kept sharpened yellow pencil to paper until he was 74, all the while preoccupied with what he described as "a constant unholy terror of boring the reader." He died of leukemia in 1990, at home at Gipsy House. Dahl has been compared to a magician, Willy Wonka and the Big Friendly Giant. He always had one goal as an author, and that was to grab his readers and not let go. As he wrote in an essay called "Ideas to Help Aspiring Writers" in The Roald Dahl Treasury, "...as I write my stories I always try to create situations that will cause my reader to 1) Laugh (actual loud belly laughs) 2) Squirm 3) Become enthralled 4) Become TENSE and EXCITED and say, "Read on! Please read on! Don't stop!" And that's exactly what his readers do. We squirm, laugh actual loud belly laughs, brace for his one-two punches, and wish there were more "absolutely squiffling" books by Roald Dahl. --Karin Snelson, children's & YA editor, Shelf Awareness

Penguin Young Readers and the Roald Dahl Literary Estate are launching "Roald Dahl 100," a global, yearlong celebration marking the 100th anniversary of Dahl's birth, including a Roald Dahl birthday party in bookstores, libraries, classrooms and public places across the U.S. on September 13, 2016.

Roald Dahl: A Peach of a Poet

As a child, Dahl was more interested in photography, cricket, or childish pranks than in words. He was born in Wales on September 13, 1916, to Norwegian parents. Dahl's later childhood straddled two very different worlds--long and glorious summers in Norway, and the rigors of English boarding schools during the academic year. Dahl's memories of sadistic, cane-happy headmasters would infuse his work for the rest of his days. Adults are often frightening, repulsive, even filthy creatures in his fantastical stories. Both the noblest and nastiest extremes of humankind are represented, often with the noblest (a child), destroying the nastiest (an adult), in a ghastly act of revenge for some injustice. In a jolly-metered poem called "Mister Unsworth," first published in Vile Verses (2005), he paints a dark picture of a cruel teacher:

As a child, Dahl was more interested in photography, cricket, or childish pranks than in words. He was born in Wales on September 13, 1916, to Norwegian parents. Dahl's later childhood straddled two very different worlds--long and glorious summers in Norway, and the rigors of English boarding schools during the academic year. Dahl's memories of sadistic, cane-happy headmasters would infuse his work for the rest of his days. Adults are often frightening, repulsive, even filthy creatures in his fantastical stories. Both the noblest and nastiest extremes of humankind are represented, often with the noblest (a child), destroying the nastiest (an adult), in a ghastly act of revenge for some injustice. In a jolly-metered poem called "Mister Unsworth," first published in Vile Verses (2005), he paints a dark picture of a cruel teacher: Dahl first wrote for adults, but ultimately found his best audience when he had children of his own to regale with stories. His daughter Ophelia, one of five children Dahl had with American actress Patricia Neal, recalled that the funny, sometimes morbid vignettes that her father told her at bedtime were the seeds of his most popular children's novels. Editor Roxburgh, who became a good friend of the family, said that Dahl was a different person around children than he was around adult colleagues or friends. "He would play the BFG," said Roxburgh. "The sentimentality in his children's work is pure, if you can ever say Dahl is pure. I think he drew heavily from his idyllic early childhood. And he loved children. That's the source of his great works."

Dahl first wrote for adults, but ultimately found his best audience when he had children of his own to regale with stories. His daughter Ophelia, one of five children Dahl had with American actress Patricia Neal, recalled that the funny, sometimes morbid vignettes that her father told her at bedtime were the seeds of his most popular children's novels. Editor Roxburgh, who became a good friend of the family, said that Dahl was a different person around children than he was around adult colleagues or friends. "He would play the BFG," said Roxburgh. "The sentimentality in his children's work is pure, if you can ever say Dahl is pure. I think he drew heavily from his idyllic early childhood. And he loved children. That's the source of his great works.".jpg) In Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, Fantastic Mr. Fox (1970) and Matilda, Dahl persisted in playing with words. In fact, it is difficult to discuss Dahl as a poet separately from Dahl as a storyteller; his poems are stories, and his stories, however "no-frills," are poetic. The BFG (1982), for instance, is a charming novel about a big friendly giant who blows dreams into the bedrooms of sleeping children at night and speaks an endearingly mangled language all his own. When the young orphan Sophie, whom he kidnaps, tells the giant she thinks his garbled English (his "terrible wigglish") is beautiful, the giant is overcome: "How whoopsy-splunkers! How absolutely squiffling! I is all of a stutter."

In Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, Fantastic Mr. Fox (1970) and Matilda, Dahl persisted in playing with words. In fact, it is difficult to discuss Dahl as a poet separately from Dahl as a storyteller; his poems are stories, and his stories, however "no-frills," are poetic. The BFG (1982), for instance, is a charming novel about a big friendly giant who blows dreams into the bedrooms of sleeping children at night and speaks an endearingly mangled language all his own. When the young orphan Sophie, whom he kidnaps, tells the giant she thinks his garbled English (his "terrible wigglish") is beautiful, the giant is overcome: "How whoopsy-splunkers! How absolutely squiffling! I is all of a stutter." Dirty Beasts is also crawling with story-poems about vigilante justice, Dahl-style. When the pig eats the farmer before the farmer eats him in "The Pig," readers can imagine Dahl's boarding-school fantasies at work. Many of the poems seem bent on frightening the wits out of children at bedtime. Three-quarters into a poem about a crocodile who likes to eat children, the narrator whispers, "Shh! Listen! What is that I hear/ Gallumphing [sic] softly up the stair?/ Go lock the door and fetch my gun!/ Go on, child, hurry! Quickly, run!"

Dirty Beasts is also crawling with story-poems about vigilante justice, Dahl-style. When the pig eats the farmer before the farmer eats him in "The Pig," readers can imagine Dahl's boarding-school fantasies at work. Many of the poems seem bent on frightening the wits out of children at bedtime. Three-quarters into a poem about a crocodile who likes to eat children, the narrator whispers, "Shh! Listen! What is that I hear/ Gallumphing [sic] softly up the stair?/ Go lock the door and fetch my gun!/ Go on, child, hurry! Quickly, run!" Jim Harrison, the prolific fiction writer, essayist and poet,

Jim Harrison, the prolific fiction writer, essayist and poet,