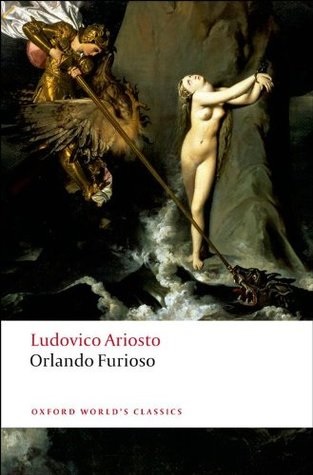

My immediate and intense connection with the Neapolitan novels by Elena Ferrante should have warned me. I am genetically prone to appreciate Italian literature. I devoured Dante in college, read him in three different translations simultaneously. I gobbled up Ludovico Ariosto, reading multiple translations of his Orlando Furioso (Oxford, $17.95), the greatest comic epic fantasy poem ever written, from first line to last. I saw every film by Federico Fellini, Michelangelo Antonioni and Pier Paolo Pasolini. But Italian novels--not until Elena Ferrante crossed my path.

My immediate and intense connection with the Neapolitan novels by Elena Ferrante should have warned me. I am genetically prone to appreciate Italian literature. I devoured Dante in college, read him in three different translations simultaneously. I gobbled up Ludovico Ariosto, reading multiple translations of his Orlando Furioso (Oxford, $17.95), the greatest comic epic fantasy poem ever written, from first line to last. I saw every film by Federico Fellini, Michelangelo Antonioni and Pier Paolo Pasolini. But Italian novels--not until Elena Ferrante crossed my path.

Once I had read Ferrante's My Brilliant Friend (L'amica geniale, 2012; available in the U.S. from Europa, $17), I became impatient waiting for each of the three subsequent volumes, wondering with the rest of the world who this anonymous writer could be, not understanding that her four-volume saga was the most recent flowering of an Italian tradition of historical realism in fiction that went back to the mid-19th century. I was ripe for discovering classic Italian novels, and was first provoked into doing so by my bookstore friend and podcast partner on Breakfast at the Bookstore, Brad Craft. "You're Italian, and you've never read The Betrothed?" he teased. "It's like Dickens for an Italian. In Italy, it's considered second only to Dante."

It was a challenge I couldn't resist. My pile of advanced copies to review was low--down to two novels, one about the horrors of the trenches in the First World War, the other about the Rwanda genocide. Not surprisingly, it felt like a very good time to put off reviewing and indulge in a little literary self-education.

It was a challenge I couldn't resist. My pile of advanced copies to review was low--down to two novels, one about the horrors of the trenches in the First World War, the other about the Rwanda genocide. Not surprisingly, it felt like a very good time to put off reviewing and indulge in a little literary self-education.

Alessandro Manzoni's The Betrothed (I Promessi Sposi, 1827; Everyman's Library, $26.95) had never looked more promising. Brad gave me a lovely hardback Everyman's Library edition in the classic translation by Archibald Colquhoun. It was irresistible--not that it was my first copy of that particular classic; I had purchased it repeatedly through my decades of reading. I was frequently discovering yet another unread copy in my collection. I simply had never read it. I searched through my library until I managed to locate a Dutton paperback version that cost $2.45 back in the '60s, and embarked on the 600-page journey.

Manzoni wrote one great novel in his lifetime, but published it three different times, constantly amplifying and improving it. Modeled on the historical novels of Sir Walter Scott, with a hero and heroine from the working class, corrupt aristocrats and less-than-genuine religious folk, The Betrothed is like a big literary lasagna--a layer of history, a layer of comic monologue, a layer of romance, a layer of religious life. It was the birth of a new literary form in Italian literature. It's a huge panorama of society, but oddly static, almost like a medieval tapestry the way the characters seem to freeze and become emblematic.

In the same way that creating the hobbit was Tolkien's stroke of genius, Manzoni's epic is wisely lightened by Don Abbondio, the delightfully cowardly village priest who succumbs to the villain's threats and refuses to marry the titular couple, setting the novel into motion. How that plot intersects with the unification of Italy, the bread riots of Milan and the plague forms a saga that has been filmed multiple times and made into two operas. Its most famous scenes are as familiar to Italians as the river-rafting escapades of Huckleberry Finn are to Americans, and the literary inventions of The Betrothed paved the way for Umberto Eco to create a similar historical masterpiece, The Name of the Rose (Mariner, $15.95).

In the same way that creating the hobbit was Tolkien's stroke of genius, Manzoni's epic is wisely lightened by Don Abbondio, the delightfully cowardly village priest who succumbs to the villain's threats and refuses to marry the titular couple, setting the novel into motion. How that plot intersects with the unification of Italy, the bread riots of Milan and the plague forms a saga that has been filmed multiple times and made into two operas. Its most famous scenes are as familiar to Italians as the river-rafting escapades of Huckleberry Finn are to Americans, and the literary inventions of The Betrothed paved the way for Umberto Eco to create a similar historical masterpiece, The Name of the Rose (Mariner, $15.95).

Manzoni's achievement is often compared with that of Giuseppe di Lampedusa, the Sicilian aristocrat whose novel, The Leopard (Il Gattopardo, 1958), was a similar one-book-in-a-lifetime creation by an Italian genius. Unfortunately, di Lampedusa died with his novel rejected and unpublished. After a long search, I finally found a pristine, unread Avon paperback for $1.75, back from when it was first published in the '60s, and translated by the very same Archibald Colquhoun.

It's a completely different reading experience, mostly psychological interior stuff. Filled with elegant language, sumptuous descriptions and realistic motivations, it's the story of the last melancholy days of the Italian aristocracy as Garibaldi and the unification of Italy reduce them to memories. Though history is changing everything around the novel's protagonist, Prince Fabrizio, most of The Leopard (Pantheon, $16) is not about the action.

The characterization of the prince within his historical context is one of the novel's supreme strengths. But other portions feel fragmentary and unconnected, and a concluding chapter takes place many years later. Apparently there is even yet another uncompleted and unpublished portion. The success of the novel peaks with the penultimate chapter, "Death of a Prince"; di Lampedusa's lyrical assessment of approaching death is unsurpassed. But when the plot wanders away from Prince Fabrizio, the novel feels like a majestic crumbling ruin, like the aristocracy it describes.

The characterization of the prince within his historical context is one of the novel's supreme strengths. But other portions feel fragmentary and unconnected, and a concluding chapter takes place many years later. Apparently there is even yet another uncompleted and unpublished portion. The success of the novel peaks with the penultimate chapter, "Death of a Prince"; di Lampedusa's lyrical assessment of approaching death is unsurpassed. But when the plot wanders away from Prince Fabrizio, the novel feels like a majestic crumbling ruin, like the aristocracy it describes.

Luchino Visconti's brilliant three-hour film adaptation (1963) wisely leaves out everything that doesn't have to do with the Prince. Considered by some among the greatest films of all time, the main events in the film are an inappropriate earthy laugh at the dinner table and a ballroom dance. What Visconti does with those two moments is unforgettable.

The Leopard might have exhausted my Italian plunge had I not noticed on one of my bookstore's display tables a book Brad endorsed, Life in the Country by Giovanni Verga (Hesperus, $13.95). In it are classic Italian stories, including the basis of the opera Cavalleria rusticana, and the sight of it reminded me that I used to have an old Signet Classic copy of Verga's most famous work, a novel called The House by the Medlar Tree (I Malavoglia, 1881; Dedalus, $15.99). An exhaustive search through my home library managed to locate it. And the moment I discovered that D.H. Lawrence had been so captivated by Verga that he had translated the novel himself, the cycle began again.

For a novel published 135 years ago, the shock is that it's head-spinningly modern. No sentimental stereotypes here; these are uneducated peasants. No fancy language; Verga uses the language of the people. He begins his tale of the poor inhabitants of a Sicilian fishing village by plopping the reader down in their midst and casually throwing out the names of half the village with no introductions. The reader has no choice but simply to go with it and try to remember whatever possible. It works. The names easily become familiar. It's sheer literary magic.

For a novel published 135 years ago, the shock is that it's head-spinningly modern. No sentimental stereotypes here; these are uneducated peasants. No fancy language; Verga uses the language of the people. He begins his tale of the poor inhabitants of a Sicilian fishing village by plopping the reader down in their midst and casually throwing out the names of half the village with no introductions. The reader has no choice but simply to go with it and try to remember whatever possible. It works. The names easily become familiar. It's sheer literary magic.

He brings to life dozens of characters: the pharmacist, the tavern keeper, the priest, the moneylender, fishermen, farmers and their wives and children. These people dream, curse, fight, love and pursue each other. The story is infested with small-town hostilities and secrets, and when these characters get worked up, they throw proverbs at each other. Deaths at sea cause economic upheavals; the storm-at-sea sequence is appropriately hair-raising and profoundly moving. Verga's characters are as concerned about marriage, money and inheritance as any character in Jane Austen. With a realism that predates the realistic villagers of Jean Giono by 30 years, Verga's tragicomic Sicilian village life comes out of nowhere in literature, refreshingly candid and exhilaratingly spare. As with The Leopard, Luchino Visconti made a film of The House by the Medlar Tree, although he changed the name to La Terra Trema; he filmed in a Sicilian village, casting real Sicilian fishermen and villagers in the cast.

Thank you, Brad, for such a glorious detour in my library and my literary heritage. These classic Italian novels were ones I had purchased more than 50 years ago, kept in my collection and moved laboriously in boxes from house to house, unread. Now they have become my treasures, out of print editions, in perfect condition--and a living testament to why paper-ink-and-glue books matter. --Nick DiMartino, Nick's Picks, University Book Store, Seattle, Wash.

Thank you, Brad, for such a glorious detour in my library and my literary heritage. These classic Italian novels were ones I had purchased more than 50 years ago, kept in my collection and moved laboriously in boxes from house to house, unread. Now they have become my treasures, out of print editions, in perfect condition--and a living testament to why paper-ink-and-glue books matter. --Nick DiMartino, Nick's Picks, University Book Store, Seattle, Wash.

Discovering Classic Italian Novels

Soup Nights offers all sorts of culinary adventures: some are perfect for vegetarians, others focus on fish (bouillabaisse and gumbo), and many highlight nutrient-rich beans and grains (barley, quinoa, lentils and beans of varying hues). You will also find hearty, richly flavored options, such as classic onion soup gratiné to counter weather's chill, as well as cooler choices, like an icy cucumber Vichyssoise, for sweltering days.

Soup Nights offers all sorts of culinary adventures: some are perfect for vegetarians, others focus on fish (bouillabaisse and gumbo), and many highlight nutrient-rich beans and grains (barley, quinoa, lentils and beans of varying hues). You will also find hearty, richly flavored options, such as classic onion soup gratiné to counter weather's chill, as well as cooler choices, like an icy cucumber Vichyssoise, for sweltering days.

Billy Lynn's Long Halftime Walk by Ben Fountain was a National Book Award finalist, winner of the National Book Critics Circle Award for Fiction, and the basis for a film by Ang Lee that opens this Friday. Fountain's debut novel follows the eight members of Bravo Squad, a unit of U.S. soldiers brought home from Iraq for a "Victory Tour" after a bloody skirmish is captured on video. 19-year-old Billy Lynn and his comrades are to be set pieces of the halftime show of the Dallas Cowboys' Thanksgiving game. The novel takes place in a single day at the stadium, with several flashbacks, where Billy confronts the harsh, sometimes satirical disconnect between his role as a wartime soldier and a homefront that experiences so little sacrifice.

Billy Lynn's Long Halftime Walk by Ben Fountain was a National Book Award finalist, winner of the National Book Critics Circle Award for Fiction, and the basis for a film by Ang Lee that opens this Friday. Fountain's debut novel follows the eight members of Bravo Squad, a unit of U.S. soldiers brought home from Iraq for a "Victory Tour" after a bloody skirmish is captured on video. 19-year-old Billy Lynn and his comrades are to be set pieces of the halftime show of the Dallas Cowboys' Thanksgiving game. The novel takes place in a single day at the stadium, with several flashbacks, where Billy confronts the harsh, sometimes satirical disconnect between his role as a wartime soldier and a homefront that experiences so little sacrifice. My immediate and intense connection with the Neapolitan novels by Elena Ferrante should have warned me. I am genetically prone to appreciate Italian literature. I devoured Dante in college, read him in three different translations simultaneously. I gobbled up Ludovico Ariosto, reading multiple translations of his Orlando Furioso (Oxford, $17.95), the greatest comic epic fantasy poem ever written, from first line to last. I saw every film by Federico Fellini, Michelangelo Antonioni and Pier Paolo Pasolini. But Italian novels--not until Elena Ferrante crossed my path.

My immediate and intense connection with the Neapolitan novels by Elena Ferrante should have warned me. I am genetically prone to appreciate Italian literature. I devoured Dante in college, read him in three different translations simultaneously. I gobbled up Ludovico Ariosto, reading multiple translations of his Orlando Furioso (Oxford, $17.95), the greatest comic epic fantasy poem ever written, from first line to last. I saw every film by Federico Fellini, Michelangelo Antonioni and Pier Paolo Pasolini. But Italian novels--not until Elena Ferrante crossed my path. It was a challenge I couldn't resist. My pile of advanced copies to review was low--down to two novels, one about the horrors of the trenches in the First World War, the other about the Rwanda genocide. Not surprisingly, it felt like a very good time to put off reviewing and indulge in a little literary self-education.

It was a challenge I couldn't resist. My pile of advanced copies to review was low--down to two novels, one about the horrors of the trenches in the First World War, the other about the Rwanda genocide. Not surprisingly, it felt like a very good time to put off reviewing and indulge in a little literary self-education. In the same way that creating the hobbit was Tolkien's stroke of genius, Manzoni's epic is wisely lightened by Don Abbondio, the delightfully cowardly village priest who succumbs to the villain's threats and refuses to marry the titular couple, setting the novel into motion. How that plot intersects with the unification of Italy, the bread riots of Milan and the plague forms a saga that has been filmed multiple times and made into two operas. Its most famous scenes are as familiar to Italians as the river-rafting escapades of Huckleberry Finn are to Americans, and the literary inventions of The Betrothed paved the way for Umberto Eco to create a similar historical masterpiece, The Name of the Rose (Mariner, $15.95).

In the same way that creating the hobbit was Tolkien's stroke of genius, Manzoni's epic is wisely lightened by Don Abbondio, the delightfully cowardly village priest who succumbs to the villain's threats and refuses to marry the titular couple, setting the novel into motion. How that plot intersects with the unification of Italy, the bread riots of Milan and the plague forms a saga that has been filmed multiple times and made into two operas. Its most famous scenes are as familiar to Italians as the river-rafting escapades of Huckleberry Finn are to Americans, and the literary inventions of The Betrothed paved the way for Umberto Eco to create a similar historical masterpiece, The Name of the Rose (Mariner, $15.95). The characterization of the prince within his historical context is one of the novel's supreme strengths. But other portions feel fragmentary and unconnected, and a concluding chapter takes place many years later. Apparently there is even yet another uncompleted and unpublished portion. The success of the novel peaks with the penultimate chapter, "Death of a Prince"; di Lampedusa's lyrical assessment of approaching death is unsurpassed. But when the plot wanders away from Prince Fabrizio, the novel feels like a majestic crumbling ruin, like the aristocracy it describes.

The characterization of the prince within his historical context is one of the novel's supreme strengths. But other portions feel fragmentary and unconnected, and a concluding chapter takes place many years later. Apparently there is even yet another uncompleted and unpublished portion. The success of the novel peaks with the penultimate chapter, "Death of a Prince"; di Lampedusa's lyrical assessment of approaching death is unsurpassed. But when the plot wanders away from Prince Fabrizio, the novel feels like a majestic crumbling ruin, like the aristocracy it describes. For a novel published 135 years ago, the shock is that it's head-spinningly modern. No sentimental stereotypes here; these are uneducated peasants. No fancy language; Verga uses the language of the people. He begins his tale of the poor inhabitants of a Sicilian fishing village by plopping the reader down in their midst and casually throwing out the names of half the village with no introductions. The reader has no choice but simply to go with it and try to remember whatever possible. It works. The names easily become familiar. It's sheer literary magic.

For a novel published 135 years ago, the shock is that it's head-spinningly modern. No sentimental stereotypes here; these are uneducated peasants. No fancy language; Verga uses the language of the people. He begins his tale of the poor inhabitants of a Sicilian fishing village by plopping the reader down in their midst and casually throwing out the names of half the village with no introductions. The reader has no choice but simply to go with it and try to remember whatever possible. It works. The names easily become familiar. It's sheer literary magic. Thank you, Brad, for such a glorious detour in my library and my literary heritage. These classic Italian novels were ones I had purchased more than 50 years ago, kept in my collection and moved laboriously in boxes from house to house, unread. Now they have become my treasures, out of print editions, in perfect condition--and a living testament to why paper-ink-and-glue books matter. --

Thank you, Brad, for such a glorious detour in my library and my literary heritage. These classic Italian novels were ones I had purchased more than 50 years ago, kept in my collection and moved laboriously in boxes from house to house, unread. Now they have become my treasures, out of print editions, in perfect condition--and a living testament to why paper-ink-and-glue books matter. --