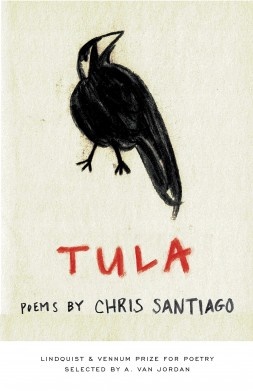

Chris Santiago is the author of Tula (Milkweed, $16), winner of the 2016 Lindquist & Vennum Prize for Poetry, selected by A. Van Jordan. Santiago's poems, fiction and criticism have appeared in FIELD, Copper Nickel, Pleiades and the Asian American Literary Review. He holds degrees in creative writing and music from Oberlin College and received his Ph.D. in English from the University of Southern California. The recipient of fellowships from Kundiman and the Mellon Foundation/American Council of Learned Societies, Santiago is also a percussionist and amateur jazz pianist. He teaches literature, sound culture and creative writing at the University of St. Thomas. He lives in Minnesota.

Chris Santiago is the author of Tula (Milkweed, $16), winner of the 2016 Lindquist & Vennum Prize for Poetry, selected by A. Van Jordan. Santiago's poems, fiction and criticism have appeared in FIELD, Copper Nickel, Pleiades and the Asian American Literary Review. He holds degrees in creative writing and music from Oberlin College and received his Ph.D. in English from the University of Southern California. The recipient of fellowships from Kundiman and the Mellon Foundation/American Council of Learned Societies, Santiago is also a percussionist and amateur jazz pianist. He teaches literature, sound culture and creative writing at the University of St. Thomas. He lives in Minnesota.

You open Tula with an incredible image of a pencil piercing the cochlea, where nerves respond to sound vibrations. Where did your fascination with sound and language begin?

I'm glad you liked that image; it was a thing that actually happened, but only after the fact did I stop and think about how arresting it might be.

I think my fascination with sound and language has always been there, although I didn't become conscious of it until I had spent several years thinking seriously about poetry. I'd always been fascinated by wordplay, and I've always loved puns, especially when I started studying other languages, such as Italian and Japanese. For me, there's a pure and uncomplicated joy in finding false cognates between languages, and in finding out that something quite sober in one tongue means something obscene in another! This was what I love about so many writers--Shakespeare, Robert Hayden, Gertrude Stein: yes, the line or sentences sing, but at the smaller unit, at the level of the word, there is a music, too. All young poets, I think, have to go through a kind of triage at some point, and figure out what it is that attracts them, that draws them out. I was less interested in the ironic, the flat or the discursive; I wanted poetry with mouthfeel.

Throughout the book you consider the music of language, like in the lines "ng a sound/ that will never start its own word/ not in this tongue" in "Transpacific." How does your knowledge of music influence your writing? And how does your writing influence your music?

I once had a wonderful conversation with David St. John about Philip Levine, in particular about Breath, and Levine's special phrasing, which isn't unlike a horn player's. To be a traditional musician, by which I mean one who plays an acoustic instrument or uses their voice (I'm not knocking electronic music or DJs, because I have much love for those fields as well, but they are different), you have to learn a lot about your own body. You have to learn to control your breath, your hands, your posture, your eyes. And this changes over time. Inasmuch as I'm interested in sound and language, I am interested in how that sound--how the word in all its physicality--is formed first in the body. One of my piano teachers, Josef Schwartz, liked to say that pianists are failed singers. He was trying to get me to think lyrically about the melody, in whichever hand it happened to be written; maybe, as a poet, I feel something like a failed composer, but what I'm working with are words, and the performance will, for the most part, be silent. Even though it is silent, though, I want there to be that trace of the physical, the enunciation of the words, in the reader's mind.

Your focus on the physicality of language production makes idioms like "even my lunatic/ cabbie held his tongue" in "Counting in Tagalog" come alive in slippery and surprising ways.

The poetry that I get really excited about never stops acknowledging that it quite literally speaks from a place--from language--that is both stable and incredibly unstable. It is this instability--the constantly changing nature of speech and language, and the fact that a language is a whole series of definitions with no real grounding, except for sound or shape (in the case of sign languages, for example)--that makes poetic utterance possible, in my opinion. Everything that is stable and immobile about language is unpoetic. Of course there are wonderful poets who play with this, poets who use or recover or repurpose the unpoetic (Solmaz Sharif's Look, for example, is amazing in its reworking of Defense Department terminology). But this kind of work still comments on the slipperiness of language, even if it doesn't mean to.

Literary translators speak about operating in the ether between languages. Has studying language done more to cloud or dispel that ether for you?

Literary translators speak about operating in the ether between languages. Has studying language done more to cloud or dispel that ether for you?

I think studying language has done more to expand that ether for me, and the more that ether can be expanded the better! If only every writer was a translator, too! Or more than that, if every student in the U.S. was required to learn translation at some point. Once you learn to step outside of your first tongue and look in at it as if you were an outsider, you start to realize how much your language shapes you. One of my favorite writers, the Japanese-German multigenre writer Yoko Tawada, has a story/essay translated by Susan Bernofsky as "Canned Foreign," in which the narrator gets physically ill hearing people "speak their native tongues fluently." It's as if, she argues, they are "unable to think and feel anything but what their language so readily served up to them." For a poet, that's a good place to start, to try thinking of your own language as something strange and magical.

The series of "Tula" poems constitute much of this book. Were they originally conceived as a single long poem?

Yes. In fact it was conceived as a long elegy in numbered parts, and published that way in the Asian American Literary Review. I still like that version, but when I incorporated it into a manuscript, it acted like a force of gravity and drew attention away from the other poems in the book. I was a Kundiman Fellow in 2013, and had the great fortune to work on the manuscript with Oliver de la Paz, who suggested I break the poem up into parts and scatter them throughout the book, almost like an archipelago. Once I started to think of the long poem as Tula--the contradiction there being that "tula" simply means "poem" in Tagalog, but that it was a word I hadn't known until I Googled it!--it made sense to me that each of the poems that had been scattered throughout the manuscript would also be called Tula.

Water and routes through it are a recurring image. Your poems draw parallels between the cognitive tides of language and the geographic journeys of immigration. How did you balance your family's personal experiences with drawing out a broader immigrant experience and that of being multilingual?

Part of the recurring imagery of water and routes has to do with ancestry, but in a much more remote sense. An interest in language and etymology led me to this idea of transpacific history, especially in terms of the Austronesian language groups, and how these remarkable navigators traveled from mainland Asia through the Philippines and out across the rest of the Pacific. As they did so, their languages changed and evolved, but there are still ancestral ties and links there; I love how Craig Santos Perez talks about these ideas in his "from Unincorporated Territory" poems. I love too finding that lalaki, which means "boy" in Tagalog, is lelaki in Malay. My own family's journey was by air, and not by sea; but with the poems, especially the "[Island]" series that counterbalances the "Tula" poems, I hope to think of the Pacific as both a space of ancestral dreams and lore, as a rich wholeness, replete with cultures, languages, peoples, flora and fauna, rather than as a space between one continent and the next. --Dave Wheeler, associate editor, Shelf Awareness

Chris Santiago: Poetry with Mouthfeel

Wendell Berry's 1995 Roots to the Earth, poems with wood engravings by Wesley Bates, has been reissued, with a short story included, by Counterpoint Press ($26). It's a handsome book, a fitting tribute to Berry, a national treasure. New Directions and the Christine Burgin Gallery have co-published Emily Dickinson's Envelope Poems, which were written on used envelopes ($12.95). Full-color facsimiles are paired with transcriptions of the poet's handwriting to craft a charming volume. W.S. Merwin composed the poetry of Garden Time (Copper Canyon Press, $24) as he lost his eyesight--poignant, lyrical elegies musing on time, mortality, memory.

Wendell Berry's 1995 Roots to the Earth, poems with wood engravings by Wesley Bates, has been reissued, with a short story included, by Counterpoint Press ($26). It's a handsome book, a fitting tribute to Berry, a national treasure. New Directions and the Christine Burgin Gallery have co-published Emily Dickinson's Envelope Poems, which were written on used envelopes ($12.95). Full-color facsimiles are paired with transcriptions of the poet's handwriting to craft a charming volume. W.S. Merwin composed the poetry of Garden Time (Copper Canyon Press, $24) as he lost his eyesight--poignant, lyrical elegies musing on time, mortality, memory.  Has it been a half-century since the iconic Chaim Potok's The Chosen was written? Yes, and Simon & Schuster has just published the 50th Anniversary Edition ($27). This classic coming-of-age story is enhanced with photos and essays, perfect for the first-time reader or the re-discoverer.

Has it been a half-century since the iconic Chaim Potok's The Chosen was written? Yes, and Simon & Schuster has just published the 50th Anniversary Edition ($27). This classic coming-of-age story is enhanced with photos and essays, perfect for the first-time reader or the re-discoverer. Mysterious coincidence/ concurrence often happens in publishing (as in life). An example is the publication of two Henry James books: Travels with Henry James (Nation Books, $19.99) and The Daily Henry James (University of Chicago Press, $16). Travels is a handsome edition of his dispatches from Saratoga to Ravenna--deckle-edged, compact--with period photographs and etchings. Daily was originally printed in 1911, as the "ultimate token of fandom." It was edited by Evelyn Smalley, compiled as a commonplace book--a personal collection of quotes. From The Portrait of a Lady: "I judge more than I used to--but it seems to me that I have earned the right. One can't judge till one is forty; before that we are too eager, too hard, too cruel, and in addition too ignorant." --Marilyn Dahl, editor, Shelf Awareness for Readers

Mysterious coincidence/ concurrence often happens in publishing (as in life). An example is the publication of two Henry James books: Travels with Henry James (Nation Books, $19.99) and The Daily Henry James (University of Chicago Press, $16). Travels is a handsome edition of his dispatches from Saratoga to Ravenna--deckle-edged, compact--with period photographs and etchings. Daily was originally printed in 1911, as the "ultimate token of fandom." It was edited by Evelyn Smalley, compiled as a commonplace book--a personal collection of quotes. From The Portrait of a Lady: "I judge more than I used to--but it seems to me that I have earned the right. One can't judge till one is forty; before that we are too eager, too hard, too cruel, and in addition too ignorant." --Marilyn Dahl, editor, Shelf Awareness for Readers

Chris Santiago is the author of Tula (Milkweed, $16), winner of the 2016 Lindquist & Vennum Prize for Poetry, selected by A. Van Jordan. Santiago's poems, fiction and criticism have appeared in FIELD, Copper Nickel, Pleiades and the Asian American Literary Review. He holds degrees in creative writing and music from Oberlin College and received his Ph.D. in English from the University of Southern California. The recipient of fellowships from Kundiman and the Mellon Foundation/American Council of Learned Societies, Santiago is also a percussionist and amateur jazz pianist. He teaches literature, sound culture and creative writing at the University of St. Thomas. He lives in Minnesota.

Chris Santiago is the author of Tula (Milkweed, $16), winner of the 2016 Lindquist & Vennum Prize for Poetry, selected by A. Van Jordan. Santiago's poems, fiction and criticism have appeared in FIELD, Copper Nickel, Pleiades and the Asian American Literary Review. He holds degrees in creative writing and music from Oberlin College and received his Ph.D. in English from the University of Southern California. The recipient of fellowships from Kundiman and the Mellon Foundation/American Council of Learned Societies, Santiago is also a percussionist and amateur jazz pianist. He teaches literature, sound culture and creative writing at the University of St. Thomas. He lives in Minnesota. Literary translators speak about operating in the ether between languages. Has studying language done more to cloud or dispel that ether for you?

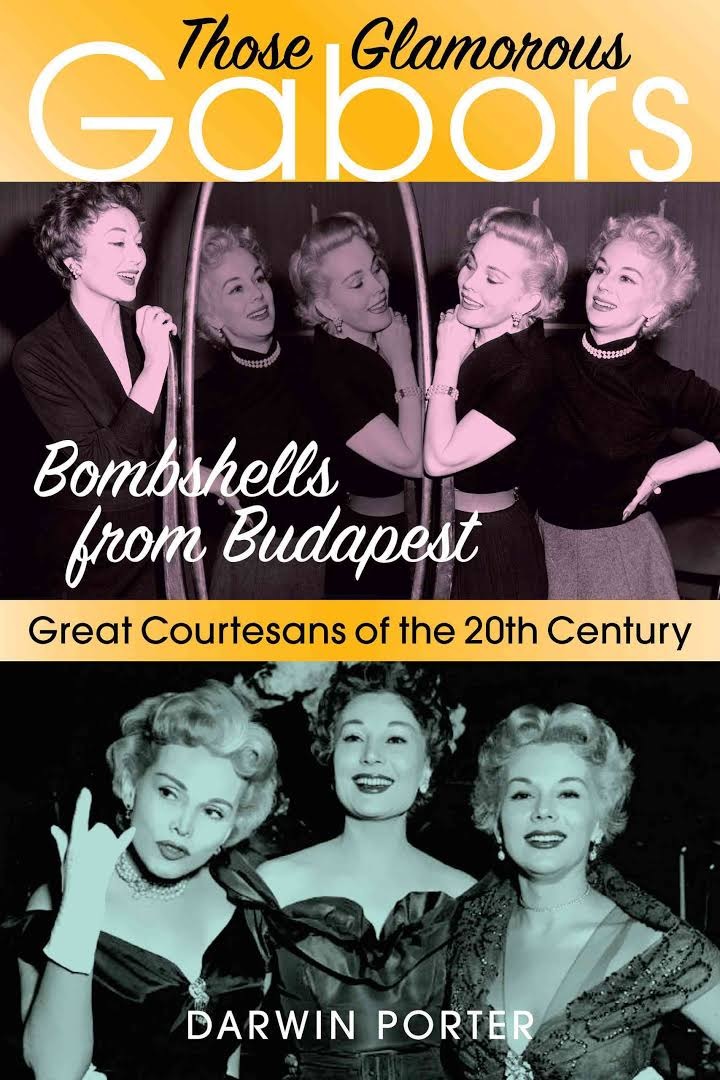

Literary translators speak about operating in the ether between languages. Has studying language done more to cloud or dispel that ether for you? Zsa Zsa Gabor, an icon of yesteryear Hollywood, died on Sunday at age 99. She was born as Sári Gábor in 1917 in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Gabor began her career on stage in Vienna, and was crowned Miss Hungary in 1936 before emigrating to the U.S. in 1941. Her Hollywood acting career took off in 1952, with parts in Moulin Rouge, Lovely to Look At and We're Not Married! Zsa Zsa appeared in other films, often in cameos, during the following decades, but her most famous role was as an extravagant socialite. Gerold Frank, who co-authored Gabor's 1960 autobiography, described her as "a woman from the court of Louis XV who has somehow managed to live in the 20th century."

Zsa Zsa Gabor, an icon of yesteryear Hollywood, died on Sunday at age 99. She was born as Sári Gábor in 1917 in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Gabor began her career on stage in Vienna, and was crowned Miss Hungary in 1936 before emigrating to the U.S. in 1941. Her Hollywood acting career took off in 1952, with parts in Moulin Rouge, Lovely to Look At and We're Not Married! Zsa Zsa appeared in other films, often in cameos, during the following decades, but her most famous role was as an extravagant socialite. Gerold Frank, who co-authored Gabor's 1960 autobiography, described her as "a woman from the court of Louis XV who has somehow managed to live in the 20th century."