|

| photo: Chad Griffith |

Bestselling author and winner of multiple awards, including the Edgar Award for best first book, Joseph Kanon returns with The Defectors (out now from Atria Books). Set during the height of the Cold War, Kanon's eighth novel is remarkably relevant today despite its historical setting. Here, Kanon discusses Russia, the devil we knew, and how it never really went away.

It was always wishful thinking that the KGB would go away. When the Soviet Union imploded in 1991, thriller writers may have felt they had lost their bad guys for good. For nearly half a century, novelists played cat and mouse with these familiar villains in trench coats--and the more serious found in the morally compromised Cold War agents a metaphor for even larger ethical concerns. Now what? The Nazis had receded into the historical past, the Middle East was a hopeless muddle, and spies bought or blackmailed were not nearly as interesting as those who had done it for ideological reasons, the true believers of the 1930s who gave the KGB its golden era of Western humint. In real life, the most important geopolitical player--and one with a known taste for espionage--was now China, but China is opaque to most Westerners, a country largely unknown. Russia was the devil we knew and even thought we understood. And now, as source material for thriller writers, it was gone.

We needn't have worried. Even a quick glance at the front tables of any bookstore (not to mention nightly reports on cable news) shows us that Russia is back, once again the "main adversary" (KGB-speak for the U.S.). In part this is because Russia insists. Never mind that after '91 its superpower status was over. With a GNP now said to be less than that of Italy's, Russia's ability to wield international influence lies largely in its determination to make mischief and for that it has, as it has always had, one supreme resource: its intelligence service. There are other countries with proud histories in secret intelligence--Britain and Israel, to name an obvious two--but no society has embraced it for so long or with such fervor. Since at least tsarist times, espionage--domestic and foreign--has been part of Russia's DNA. No matter what its current initials--NKVD, KGB, FSB--the secret intelligence service operates as Russia's state within a state, the state that nurtured Putin, that has always seen itself as the elite arm of a superpower, feared and mythologized.

When I began writing Defectors, a novel about Western spies exiled in Moscow in 1961, I never expected it to be timely or relevant--I thought the Cold War was over. I hadn't predicted the willful resilience of the KGB, although I should have, since its special status in (then) Soviet society is very much part of the story. In 1961 the KGB had its own food stores, its own hospital, its own compound of country dachas. It prided itself on protecting its agents in the field--and bringing them "home" if they were threatened with exposure. It then welcomed them as heroes, assigned them desirable flats, gave them privileges. And kept them under surveillance for the rest of their lives.

My protagonist, Frank Weeks, fair-haired boy of the OSS and the new CIA, who defected in 1950 and now wants to write his memoirs, is fictional, but the Moscow he inhabits in many of its details is the real city the defectors knew. Kim Philby, Guy Burgess, Donald Maclean, George Blake, Morris and Lona Cohen--these are, for the most part, just names now, their Cold War notoriety largely forgotten. Their defections were scandals at the time--and then they vanished. But their stories didn't end with their defections. Philby lived in Moscow for 25 years. I wanted to know how they had lived, how they spent their time. So I went to Moscow to track down their apartments, the restaurants they'd liked, etc. It was, of course, a very different Moscow in 1961 (no hotel rooftop bars with Kremlin views then), but many of the sites still exist and found their way into Defectors.

My protagonist, Frank Weeks, fair-haired boy of the OSS and the new CIA, who defected in 1950 and now wants to write his memoirs, is fictional, but the Moscow he inhabits in many of its details is the real city the defectors knew. Kim Philby, Guy Burgess, Donald Maclean, George Blake, Morris and Lona Cohen--these are, for the most part, just names now, their Cold War notoriety largely forgotten. Their defections were scandals at the time--and then they vanished. But their stories didn't end with their defections. Philby lived in Moscow for 25 years. I wanted to know how they had lived, how they spent their time. So I went to Moscow to track down their apartments, the restaurants they'd liked, etc. It was, of course, a very different Moscow in 1961 (no hotel rooftop bars with Kremlin views then), but many of the sites still exist and found their way into Defectors.

But how had they felt about their lives? These were people who had sacrificed everything--betrayed everyone, their families, their country--for Communism and now found themselves living it. What happened to field agents who no longer had a field? Their very presence in Moscow exposed the fault line between Communism's international ideals and traditional Russian xenophobia. They may have been Soviet heroes, but they were foreign, people to be avoided. Defection was a one-way ticket--they had traded the threat of one prison for the reality of another. The defectors reacted in a variety of ways--some couldn't adjust, and drank themselves into early graves, some tried to become part of Soviet life, some made pathetic attempts to be useful to "the service" that no longer needed them. But whatever ambivalent feelings they had about the Soviet system and the choices they'd made, they remained loyal to the idea of the KGB as an elite institution. Philby even pretended to have an officer status he was never given.

In 1961 it was still possible to feel you were on the right side of history in Moscow (one of the reasons I set the novel then). But I suspect that the defectors wouldn't be surprised to see that the KGB has survived the sclerotic last days of the Soviet empire, then its collapse, then the kleptocracy that followed and even the new strong-man era, to find itself once again the bogeyman of Western writers, its mythology, if not intact, at least going strong.

After all, they were part of that mythology. The penetration of the corridors of power in Washington and London in the 1930s and 1940s has perhaps never been equaled, an intelligence triumph. If the aftermath for these defectors was less triumphal, a gray twilit existence, they never abandoned their belief in the KGB's professionalism and the superiority they felt it gave them. Maybe, like Western thrillers, they needed the KGB to be a worthy adversary--the only part of their Communist dream that still lives on.

Joseph Kanon: Russia Is Back

For the history buff, consider Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI (Doubleday) by David Graan. As their tribe numbers dwindle due to the buffalo population dying off, the Osage Nation negotiates a deal with the government for land in northeast Oklahoma. The tribe's lawyer secures mineral rights and, in 1894 when oil is discovered, the Osage are rich. Shortly thereafter, members begin to die under mysterious circumstances. Our reviewer calls it "the sterling history of this forgotten drama that precipitated the first successful major crime prosecution by J. Edgar Hoover's fledgling Federal Bureau of Investigation."

For the history buff, consider Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI (Doubleday) by David Graan. As their tribe numbers dwindle due to the buffalo population dying off, the Osage Nation negotiates a deal with the government for land in northeast Oklahoma. The tribe's lawyer secures mineral rights and, in 1894 when oil is discovered, the Osage are rich. Shortly thereafter, members begin to die under mysterious circumstances. Our reviewer calls it "the sterling history of this forgotten drama that precipitated the first successful major crime prosecution by J. Edgar Hoover's fledgling Federal Bureau of Investigation." A fatherly fiction fan will enjoy Fredrick Backman's new novel, Beartown (Atria). If a deteriorating city's junior-level hockey team wins the national semi-finals, they could bring a hockey academy and a new arena (with jobs, prosperity and pride) to a town in desperate need of hope. With everything riding on a team of teenage boys, one fateful night will change everything.

A fatherly fiction fan will enjoy Fredrick Backman's new novel, Beartown (Atria). If a deteriorating city's junior-level hockey team wins the national semi-finals, they could bring a hockey academy and a new arena (with jobs, prosperity and pride) to a town in desperate need of hope. With everything riding on a team of teenage boys, one fateful night will change everything. Tickle your father's funny bone with Letterman: The Last Giant of Late Night (Harper) by Jason Zinoman. Notorious for being as witty onscreen as he was difficult off, David Letterman spent 33 years as king of the late-night talk show. This biography includes material from interviews with the man himself as well as his writers, producers and others who worked closely with him. Letterman is a frank tribute to the painful process of creating comedy.

Tickle your father's funny bone with Letterman: The Last Giant of Late Night (Harper) by Jason Zinoman. Notorious for being as witty onscreen as he was difficult off, David Letterman spent 33 years as king of the late-night talk show. This biography includes material from interviews with the man himself as well as his writers, producers and others who worked closely with him. Letterman is a frank tribute to the painful process of creating comedy. The Great Unknown: Seven Journeys to the Frontiers of Science by Marcus du Sautoy (Viking) is perfect for the science-minded dad. "Du Sautoy investigates the frontiers of mathematical and scientific ideas, sorted into broad concepts such as Chaos, Matter, Consciousness and Infinity, and set in the context of history, evolution, philosophy, literature and music." Exploring the potential limits of human knowledge with a clear, concise, and entertaining voice, this is a great gift for anyone with curiosity about scientific inquiry and the deep mysteries of the universe.

The Great Unknown: Seven Journeys to the Frontiers of Science by Marcus du Sautoy (Viking) is perfect for the science-minded dad. "Du Sautoy investigates the frontiers of mathematical and scientific ideas, sorted into broad concepts such as Chaos, Matter, Consciousness and Infinity, and set in the context of history, evolution, philosophy, literature and music." Exploring the potential limits of human knowledge with a clear, concise, and entertaining voice, this is a great gift for anyone with curiosity about scientific inquiry and the deep mysteries of the universe.

My protagonist, Frank Weeks, fair-haired boy of the OSS and the new CIA, who defected in 1950 and now wants to write his memoirs, is fictional, but the Moscow he inhabits in many of its details is the real city the defectors knew. Kim Philby, Guy Burgess, Donald Maclean, George Blake, Morris and Lona Cohen--these are, for the most part, just names now, their Cold War notoriety largely forgotten. Their defections were scandals at the time--and then they vanished. But their stories didn't end with their defections. Philby lived in Moscow for 25 years. I wanted to know how they had lived, how they spent their time. So I went to Moscow to track down their apartments, the restaurants they'd liked, etc. It was, of course, a very different Moscow in 1961 (no hotel rooftop bars with Kremlin views then), but many of the sites still exist and found their way into Defectors.

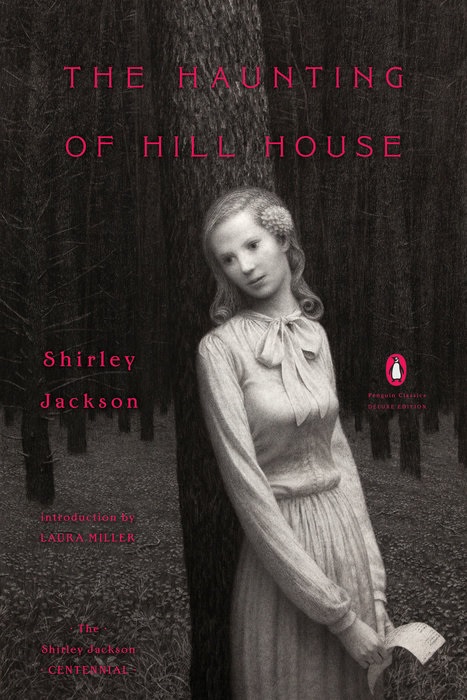

My protagonist, Frank Weeks, fair-haired boy of the OSS and the new CIA, who defected in 1950 and now wants to write his memoirs, is fictional, but the Moscow he inhabits in many of its details is the real city the defectors knew. Kim Philby, Guy Burgess, Donald Maclean, George Blake, Morris and Lona Cohen--these are, for the most part, just names now, their Cold War notoriety largely forgotten. Their defections were scandals at the time--and then they vanished. But their stories didn't end with their defections. Philby lived in Moscow for 25 years. I wanted to know how they had lived, how they spent their time. So I went to Moscow to track down their apartments, the restaurants they'd liked, etc. It was, of course, a very different Moscow in 1961 (no hotel rooftop bars with Kremlin views then), but many of the sites still exist and found their way into Defectors. December 14, 2016, marked the 100th anniversary of Shirley Jackson's birth. Among other centennial celebrations, Penguin Classics released a special deluxe edition of Jackson's The Haunting of Hill House, with an evocative new cover by artist Aron Wiesenfeld ($18, 9780143129370). Though Jackson is perhaps best known for her short story "The Lottery," which has shocked many students over the years with its macabre twist on New England village life, her novels The Bird's Nest (1954), The Sundial (1958) and We Have Always Lived in the Castle (1962) cemented her legacy as a master of subtle psychological terror.

December 14, 2016, marked the 100th anniversary of Shirley Jackson's birth. Among other centennial celebrations, Penguin Classics released a special deluxe edition of Jackson's The Haunting of Hill House, with an evocative new cover by artist Aron Wiesenfeld ($18, 9780143129370). Though Jackson is perhaps best known for her short story "The Lottery," which has shocked many students over the years with its macabre twist on New England village life, her novels The Bird's Nest (1954), The Sundial (1958) and We Have Always Lived in the Castle (1962) cemented her legacy as a master of subtle psychological terror.