|

| photo: David Kumin |

Heather Harpham is an award-winning playwright and solo performance artist whose work has been produced worldwide. She earned an MA in Theater and an MFA in Creative Writing from New York University. An essayist and fiction writer, she teaches at Sarah Lawrence College and SUNY Purchase. Happiness: The Crooked Little Road to Semi-Ever After (Holt) is her first book. Harpham is originally from the San Francisco Bay Area; she and her family now live along the Hudson River in New York State.

In Happiness, the reader has a definite sense of feeling part of the scene and connected with everything that's happening, particularly when you write about your daughter, Gracie, being sick and receiving treatment in the hospital. Do you think your background as a playwright and improvisational artist helped enhance that quality of your writing?

You know, I haven't heard the book described that way yet, as having a "scenic quality" in which the reader feels they are observing reality as an audience does in theater. And I certainly didn't set out to write theatrically. That being said, I'm really glad if that's how it comes across. One thing I discovered early on was that most of what I'd written for the stage was unusable for the page. However, many specific skills translate. I do think my experiences as a solo performance writer may have helped with Happiness. Playwriting requires the ability to compress an experience or story, to modulate the timing of events carefully and to gage an audience's responses moment by moment. Obviously some of those skills translate and others don't, in writing for the page. I tried to bring what worked best to telling the story of Happiness.

Before the book, you created a one-woman show that incorporated some of the material from your memoir. Tell me more about that process.

Not long after we returned to normal life, after transplant, I began working on a solo show which I thought would be--very generally--about the body's frailties and resilience. I called it Born Again. I emphatically did not want to use the material of my daughter's experience, but I did want to work out some of the philosophical questions that arose in watching her suffer. Despite what I intended, the transplant material sort of took over the show and pushed aside the more wide-angle ruminations on the body. Stories, in any form, tend to drift toward the heat. It was essential to me, in working with the transplant material, not to overwhelm the audience with the intensity of the material. I wanted it to be leavened with humor and with the perspective that time gives us, and I tried to bring those values to the book as well.

Your memoir goes deep into those kinds of experiences, ones that are emotionally charged. I'm thinking particularly of Brian's decision to leave when you're pregnant and having to go through not just a pregnancy alone but also the immediate aftermath of having a critically ill baby. How difficult were those moments to relive through your writing?

Very difficult. And in most of the first drafts I swerved around the harder material or moments. Some of the early readers of Happiness commented, "You've written us right up to the precipice and then wandered off." I learned that, as a writer, you have to write not just up to, but through the critical moments, even when they are hard to bear. But you have to do it with an awareness of the reader's presence and stamina. And you have to do it honestly, even when you don't want to. It was a challenge to do that, especially in those key decision-making scenes between Brian and I which are so integral to this story. It took a lot of writing, reading and re-writing to make sure that the presentation of my and Brian's relationship felt accurate and fair-handed. Particularly to Brian, since I was narrating, and also for my children who may read this book someday.

How long did it take to write Happiness?

About four or five years. And the events in the book happened more than a decade ago, so there's the benefit of time, of perspective and the personal reflection and insight that happens as a result. I don't think I could have written this story without having some distance in the form of many years between the actual events and the writing.

There's a reference in the book to Lorrie Moore's brilliant short story, "People Like That Are the Only People Here" when, during their child's stay in the pediatric oncology unit, Lorrie's husband suggests she should take notes for future writing material. While Gracie was sick, did you keep a journal or a diary that you referred to while writing Happiness?

While I was pregnant, I wrote letters to the baby. It was a way for me to let her know, first and foremost, how much she was loved and wanted. I wrote about the hopes I had for the person she would become. During the time Gracie was in the hospital, I started a Caring Bridge page [a website for people facing medical crises to update others] because so many people had read about our family's story. Gracie had been written about in the New York Post and after reading those articles, readers had donated money for her care. At first I wrote just to update people with the facts--test results, that kind of thing. Gradually I started to write more about the emotional aspects; however, very little of the website writing is in the book because those posts didn't ultimately translate well to prose.

In addition to being a story about finding happiness and discovering our capacity to love, Happiness is also about the various forms of love, the risk of losing those we love and the vulnerability that requires.

I think that's true, or I hope so. I hope it's a story about the many ways we find and construct love with another person and within our families, and also about the power of the love we find in friendships--particularly female friendships, which are so important--or the love a community has for its most vulnerable. We felt that in Brooklyn, when Gracie was embraced and supported by complete strangers at her most fragile moment. And we saw that--the envelopment of suffering with love--in other families we met in the hospital who endured the most devastating loss possible.

As you said, love comes with huge risk, which there was plenty of during our journey. There were a lot of scary high-stakes decisions along the way. And there were moments when both Brian and I, together and individually, had to be vulnerable in order to gain what we hoped for most: a healthy, stable family.

In the aftermath of caring for a critically ill child, there's a tendency to reflect back and simply assume that of course the experience was going to turn out the way it did. That it was "meant to be." But as all of us are reminded of so often, life is full of wild swings into unknown directions. "Meant to be," I think, is something we lay on experience after the fact to make it bearable, to keep on going. And that's fine. That's human. But in our case I knew, or I know now, that Gracie's survival was never guaranteed. That nothing, as much as we want it to be, is "meant to be," by any external force. At the same time, we have our own powers of love or intention, and we can use the heck out of these. --Melissa Firman

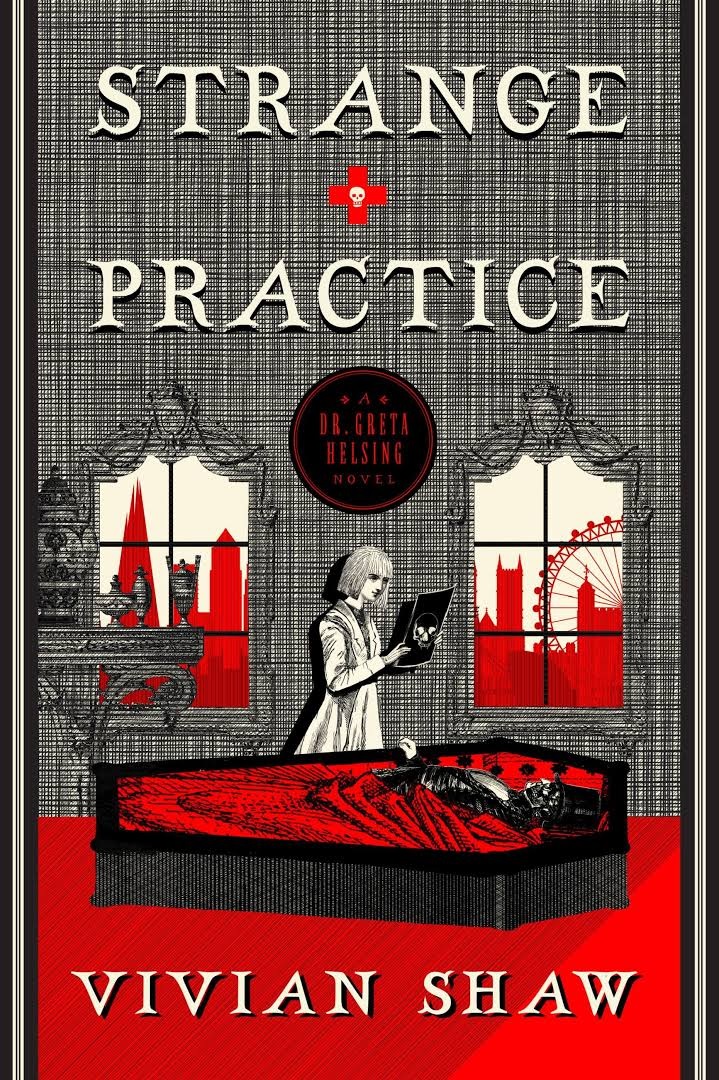

Take Strange Practice (Orbit) by Vivian Shaw. I happened to be in the area of our office where books are received when Shaw's debut arrived. The cover, a nod to Edward Gorey, caught my eye. A bit risky on the publisher's part--Gorey doesn't appeal to everyone--which made me even more curious. I flipped the book over and found a rendered Rx pad, urging banshees, barrow-wights and mummies to seek out Dr. Greta Helsing, "a first-rate physician" trained to "help you with your unnatural affliction."

Take Strange Practice (Orbit) by Vivian Shaw. I happened to be in the area of our office where books are received when Shaw's debut arrived. The cover, a nod to Edward Gorey, caught my eye. A bit risky on the publisher's part--Gorey doesn't appeal to everyone--which made me even more curious. I flipped the book over and found a rendered Rx pad, urging banshees, barrow-wights and mummies to seek out Dr. Greta Helsing, "a first-rate physician" trained to "help you with your unnatural affliction."