John Allison is an English comics writer and artist and one of the early pioneers of webcomics. He is the creator of Bobbins, Scary Go Round and, now, Bad Machinery. The newest entry, Bad Machinery, Volume 5: The Case of the Fire Inside, which was nominated for a 2017 Eisner Award in the category of Best Publication for Teens, continues the adventures of six high school crime solvers who obsess about young love and the usual problems of school and family. Shelf Awareness caught up with Allison to talk about what this nomination means to him, what the future holds for the teens of Tackleford, and how it feels to be able to cross Comic-Con off his bucket list once again.

John Allison is an English comics writer and artist and one of the early pioneers of webcomics. He is the creator of Bobbins, Scary Go Round and, now, Bad Machinery. The newest entry, Bad Machinery, Volume 5: The Case of the Fire Inside, which was nominated for a 2017 Eisner Award in the category of Best Publication for Teens, continues the adventures of six high school crime solvers who obsess about young love and the usual problems of school and family. Shelf Awareness caught up with Allison to talk about what this nomination means to him, what the future holds for the teens of Tackleford, and how it feels to be able to cross Comic-Con off his bucket list once again.

You recently tweeted that "to celebrate 10 years of not going to San Diego Comic-Con, I am going to San Diego Comic-Con." Was it the Eisner that finally got you to come out to sunny Southern California?

As the old saying goes, "if you want to lure a recalcitrant European to a far-flung comic-con, flatter his fragile ego."

Congratulations on the nomination, by the way. How are you enjoying Comic-Con?

It's very strange to be back in the convention center after a decade, because it all feels so familiar. The city has changed, though. That's where you can tell that the Con has gone from bananas to super-bananas in the last decade. It's like a celebrity version of Pokémon Go.

Let's talk a little bit about your background. You definitely have the gift of the gab when it comes to the snark of teenage dialogue. How did you get into writing and drawing comics for young audiences? And was that your goal from the get-go?

When I started writing comics, they were for people my age, which was my early 20s. But I was always able to reach people who were older. Twenty-somethings are deeply self-obsessed, but I found that the more I varied the ages I wrote, the more I enjoyed writing. Basing the Bad Machinery series around kids was an experiment--I had no idea if it would work. But it opened up lots of areas that have been interesting to work in.

You have been considered a pioneer of the webcomic format. How did you get into this medium and how has it changed in the course of your career?

I started making webcomics before they were a thing, because I knew how to make a website. I took my failed efforts to get syndicated in newspapers and made a little website for them. A few years later, this turned out to be a sustainable way to make a living--via ads, merchandise, doing cons and through work leads and commissions that came via the webcomic. It's harder for people starting out now. The delivery systems for content are splintered by social media, people don't make the same habit of visiting websites, and it's harder to grab people's attention with long-form works--though obviously some still do--but web to print is often the aim for people working that way.

Which comics artists or writers have influenced you?

Which comics artists or writers have influenced you?

I'm influenced by so many people that it's hard not to write a laundry list of people I love that offers no clues at all to what my comics are like. Chris Onstad's Achewood was a big influence on my writing, and I have spent a long time trying to be as good an artist as Meredith Gran and Bryan Lee O'Malley. I'm influenced by the greats--Posy Simmonds, Alex Toth, Mike Allred--they're called greats for a reason!

Bad Machinery is being released as a pocket series by Oni Press. Have there been significant changes to the original stories?

No changes at all beside new covers, they're just smaller books.

Some of the situations in which the kids find themselves--and I recall Volume 2's anamorphic animals--are terrifically crazy and whimsically inventive. Where do you get your plot ideas?

This will sound terribly prosaic but I wait for something that seems half-useful to occur to me, write it down, think about it for a couple of months, and wait for the story to emerge from my subconscious. It's like a tree; it emerges from the ground as a straight line, then expands into a taxonomy of ideas. If I'm lucky.

Which character in Bad Machinery do you identify with most?

They're all a little slice of me mixed with things that aren't me. Charlotte is the part of me that is a natural show-off, Sonny is the part of me that is eager to please, and so on.

Will the release of the Oni books mark the end for the Bad Machinery kids, or are there any more mysteries for the Tackleford gang to come? Like maybe a Bad Machinery: The College Years?

My other series, Giant Days, is as deep a look into the college years as I think it's possible for me to go, so I don't think we'll see the Bad Machinery kids there. The 10th case, which has recently finished online, is the last for the time being, but who knows when and where these characters might return. I'm very fond of them. --Nancy Powell, freelance writer and technical consultant

John Allison: On Mastering Snarky Language and Other Teenage Concerns

Which comics artists or writers have influenced you?

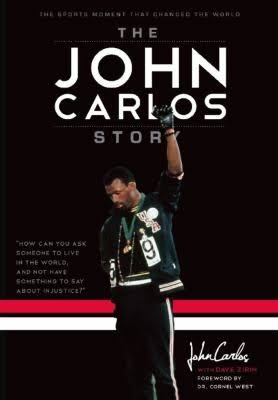

Which comics artists or writers have influenced you? On October 16, 1968, Tommie Smith and John Carlos entered the Olympic Stadium in Mexico City to accept their medals for first and third place finishes in the 200-meter sprint. They were joined on the podium by Australian silver medalist Peter Norman. As "The Star-Spangled Banner" played, Smith and Carlos bowed their heads and raised their gloved fists in a Black Power salute that shocked spectators in the stadium and the world at large. The photograph of their protest, with both men in socks and sharing a pair of gloves (hence the opposite fists), has become an iconic image in sports and civil rights history.

On October 16, 1968, Tommie Smith and John Carlos entered the Olympic Stadium in Mexico City to accept their medals for first and third place finishes in the 200-meter sprint. They were joined on the podium by Australian silver medalist Peter Norman. As "The Star-Spangled Banner" played, Smith and Carlos bowed their heads and raised their gloved fists in a Black Power salute that shocked spectators in the stadium and the world at large. The photograph of their protest, with both men in socks and sharing a pair of gloves (hence the opposite fists), has become an iconic image in sports and civil rights history.