|

| photo: Braden Moran |

Jessica Yu is an Academy Award-winning filmmaker known for her documentary and scripted work. As a director, she has also worked on such television shows as American Crime, Grey's Anatomy, 13 Reasons Why and The West Wing. She is a graduate of Yale University, and has written for numerous outlets, including the Los Angeles Times Magazine and Pacific News Service. Yu lives in Southern California with her husband, the writer and teacher Mark Salzman, and their two daughters, Ava and Esme. Her first book, Garden of the Lost and Abandoned (reviewed below), tells the story of a remarkable Ugandan woman who fights to reconnect children with their lost families.

You met Gladys Kalibbala while working on your documentary Misconception. What brought Gladys to your attention?

The film allowed me to explore, among other issues relating to population, how thousands of kids in Uganda end up stranded through want, misfortune or neglect. I came across this newspaper column, "Lost and Abandoned," that served to reconnect such children to family. The writer, Gladys Kalibbala, was the liaison between the kids, their relatives, the public, the police and other institutions.

Meeting her, it quickly became clear to me that Gladys was the story. She wasn't sitting at her desk, sipping tea. She was out there, boots on the ground, for these kids: tracing their villages, tracking down relatives, trying to find them a roof, a school, a meal, a doctor--whatever need was most pressing.

Misconception dealt with three individuals, so when you heard Gladys's story, what made you decide to write hers?

I was drawn to her buoyancy. This woman was doing so much of this on her own. She didn't have money, she didn't have transportation, she didn't have the backing of an NGO. But here she was, taking on the children of strangers--hundreds of them over the years. And most astonishing of all, she was cheerful! The problems she was trying to fix were grim and complex and endless, but she clearly found joy in the effort.

In 20 years of making documentaries, I'd never finished one feeling compelled to write a book. But after filming a few days with Gladys, I couldn't walk away. I needed to know: What was the inner mechanism that kept her going?

Did your filmmaking background affect the book-writing process?

I think I was helped by my background in film. In making documentaries, there are enormous challenges to the ideal of being "unobtrusive." In writing Garden, I savored the relative freedom of traveling without a crew, a schedule and loads of equipment, and that freedom enabled me to be a better observer. A deeper kind of focus is possible when you don't have to control anything.

In film, the goal is to show more than tell, so my approach to storytelling leans toward the visual. I wanted to combine Gladys's intimate perspective with a sense of these vivid environments that are so familiar to her. I was also struck by how Gladys's observations informed her approach to a child's case. Did the child have shoes? Was her face clean? Where did she sleep? Where did she cast her eyes when answering a question? Those kinds of visual details shaped the course of each story.

Gladys Kalibbala has helped many people. How did you determine which of them to feature?

Gladys Kalibbala has helped many people. How did you determine which of them to feature?

I was lucky to have a wealth of stories to choose from. I would go to Uganda to follow up on Gladys's current cases, only to return with new ones. I'd start thinking like Gladys: "How do I take this one on? What about that one? What will happen to him?"

I did follow quite a few cases that I didn't put to paper. Several of them would make strong stories, but some lacked a measure of clarity or closure that I did not have the luxury of pursuing. With others, too many of the formative events took place when I was not around.

That said, there are some ongoing stories I would still like to write. One involves a girl who was mysteriously kidnapped--it's still unclear exactly what took place before she found her way back to her family. Another involves a young motorcycle taxi driver who was horribly injured in an accident. Gladys has followed his case for years, securing medical help and training in a new profession for him. It's easier to get help for a child than an adult, but Gladys assists grownups as well, a challenge that leads to different kinds of drama.

You traveled to Uganda regularly over the course of four years. What's your most memorable experience from your time there?

The most memorable moments are reflected in the book, I hope, but there was one personal experience I will never forget. Gladys was traveling to the remote village of a young mother whose daughter had complicated medical problems. A gathering of neighbors greeted our arrival, and when I stepped out of the vehicle a tiny girl took one look at me and started crying. I gave her what I hoped was a friendly smile, but she screamed and ran away. When the grownups coaxed her out of hiding, she pointed at me, whimpering something. Everyone burst out laughing. The girl thought I was an "animal without fur" that was coming to eat her! And here I was, grinning at her with all my teeth, poor thing. She had never seen someone who looked like me. After a while, she tentatively accepted my presence. She and some of the other children made a game of jumping around me, chanting "Animal! Animal!"

It is a very educational experience, to be seen as "other." Everyone should have it.

Garden of the Lost and Abandoned conjures a beautiful array of children--many colors, sizes, shapes and types--how would you describe Gladys as a part of that garden?

The parallel of Gladys's struggle to protect her garden with her struggle to help her children was unexpected but wholly fitting. Gladys is tenacious and protective--an anchoring presence. Without getting too botanically specific, I would consider her a tree. I can just hear her asking, "Eh! What kind of tree do you think Gladys is?"

If people are inspired to help Gladys Kalibbala and her children, how can they do so?

Thank you for asking that question. I'm setting up a funding site for Gladys's garden project, which is being established as a self-sustaining source of support for her work with her kids. You can link to the page through JessicaYu.net.

What humbled me while shadowing Gladys was witnessing the benefit of hands-on involvement, even on the smallest scale. In the U.S., we talk of "compassion fatigue." We get discouraged when problems seem huge and unsolvable. But the ripple effect from even modest interventions can be immeasurable, especially as those acts accumulate over time. From Gladys, I've learned to value the daily kindness as much as the grand gesture. --Jen Forbus, freelancer

Jessica Yu: Watching a Ugandan Garden Grow

As fall turns to winter, I find myself seeking the warmth of these fires: love and questioning. While the plants and animals prepare for a season of hibernation, I prepare for a season of contemplation. My reading list reflects that: Upstream: Selected Essays by Mary Oliver, along with her collected works of poetry; When Women Were Birds: Fifty-four Variations on Voice by Terry Tempest Williams; The View from the Cheap Seats: Selected Nonfiction by Neil Gaiman.

As fall turns to winter, I find myself seeking the warmth of these fires: love and questioning. While the plants and animals prepare for a season of hibernation, I prepare for a season of contemplation. My reading list reflects that: Upstream: Selected Essays by Mary Oliver, along with her collected works of poetry; When Women Were Birds: Fifty-four Variations on Voice by Terry Tempest Williams; The View from the Cheap Seats: Selected Nonfiction by Neil Gaiman. On the surface, these are very different books. Mary Oliver writes extensively, in both her prose and her poetry, about the natural world and our place within it. Terry Tempest Williams's memoir, When Women Were Birds, is a reflection on Williams's mother and the 54 blank journals she left behind when she died, one for every year of her too-short life. Neil Gaiman seems the oddest-man out here; he's most well-known for his fantasy writings, but his nonfiction essays delve into the role of stories in shaping our lives.

On the surface, these are very different books. Mary Oliver writes extensively, in both her prose and her poetry, about the natural world and our place within it. Terry Tempest Williams's memoir, When Women Were Birds, is a reflection on Williams's mother and the 54 blank journals she left behind when she died, one for every year of her too-short life. Neil Gaiman seems the oddest-man out here; he's most well-known for his fantasy writings, but his nonfiction essays delve into the role of stories in shaping our lives. It's that "shaping our lives" part that threads through each of these disparate collections, I think, especially as it relates to love and questioning. These are not how-to guides, but rather invitations to pause: to sit and to think, to love and to question. As the days turn colder and shorter, I plan to do just that, taking in what they say about life and the shaping of it. Then, when spring unfolds on the other side of winter, I will go forth into the world and do just that. Or maybe I'll just sit and read a while longer--only time will tell. --Kerry McHugh, blogger at Entomology of a Bookworm

It's that "shaping our lives" part that threads through each of these disparate collections, I think, especially as it relates to love and questioning. These are not how-to guides, but rather invitations to pause: to sit and to think, to love and to question. As the days turn colder and shorter, I plan to do just that, taking in what they say about life and the shaping of it. Then, when spring unfolds on the other side of winter, I will go forth into the world and do just that. Or maybe I'll just sit and read a while longer--only time will tell. --Kerry McHugh, blogger at Entomology of a Bookworm

Gladys Kalibbala has helped many people. How did you determine which of them to feature?

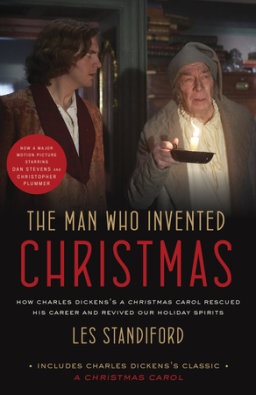

Gladys Kalibbala has helped many people. How did you determine which of them to feature?  The movie adaptation of The Man Who Invented Christmas by Les Standiford has been wreathed in rave reviews. The film, which opened November 22, stars Dan Stevens as a young Charles Dickens in the process of writing A Christmas Carol. Two years after publishing Oliver Twist, a string of unsuccessful works brings Dickens to the verge of financial ruin. He roams London for the inspiration that will allow him to deliver a manuscript in time for Christmas. As Dickens develops his story, he interacts with his characters, especially Ebenezer Scrooge (played by Christopher Plummer), and seeks advice from his Irish servant, Tara. Meanwhile, Dickens's father, John (Jonathan Pryce), tests his son's patience with financial carelessness and impropriety. As the Christmas deadline sleighs closer, Dickens's struggle to determine the fate of Scrooge intersects with his own troubled childhood.

The movie adaptation of The Man Who Invented Christmas by Les Standiford has been wreathed in rave reviews. The film, which opened November 22, stars Dan Stevens as a young Charles Dickens in the process of writing A Christmas Carol. Two years after publishing Oliver Twist, a string of unsuccessful works brings Dickens to the verge of financial ruin. He roams London for the inspiration that will allow him to deliver a manuscript in time for Christmas. As Dickens develops his story, he interacts with his characters, especially Ebenezer Scrooge (played by Christopher Plummer), and seeks advice from his Irish servant, Tara. Meanwhile, Dickens's father, John (Jonathan Pryce), tests his son's patience with financial carelessness and impropriety. As the Christmas deadline sleighs closer, Dickens's struggle to determine the fate of Scrooge intersects with his own troubled childhood.